When I first began as a graduate student encountering social media research and blogging my own thoughts, it struck me that most of the conceptual disagreements I had with various arguments stemmed from something more fundamental: the tendency to discuss “the digital” or “the internet” as a new, “virtual”, reality separate from the “physical”, “material”, “real” world. I needed a term to challenge these dualistic suppositions that (I argue) do not align with empirical realities and lived experience. Since coining “digital dualism” on this blog more than a year ago, the phrase has taken on a life of its own. I’m happy that many seem to agree, and am even more excited to continue making the case to those who do not.

When I first began as a graduate student encountering social media research and blogging my own thoughts, it struck me that most of the conceptual disagreements I had with various arguments stemmed from something more fundamental: the tendency to discuss “the digital” or “the internet” as a new, “virtual”, reality separate from the “physical”, “material”, “real” world. I needed a term to challenge these dualistic suppositions that (I argue) do not align with empirical realities and lived experience. Since coining “digital dualism” on this blog more than a year ago, the phrase has taken on a life of its own. I’m happy that many seem to agree, and am even more excited to continue making the case to those who do not.

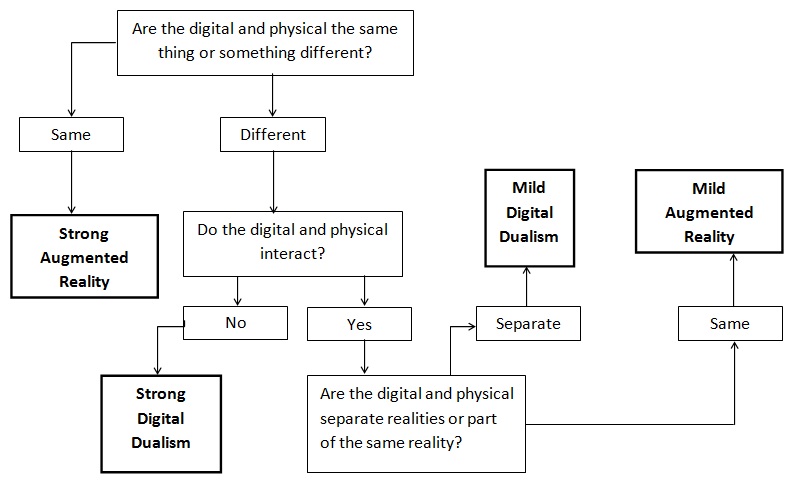

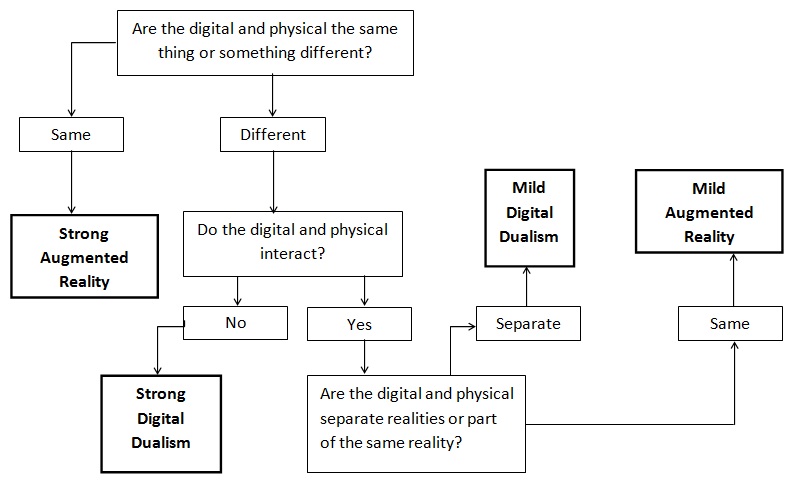

The strongest counter-argument has been that a full theory of dualistic versus synthetic models, and which is more correct, has yet to emerge. The success of the critique has so far outpaced its theoretical development, which exists in blog posts and short papers. Point taken. Blogtime runs fast, and rigorous theoretical academic papers happen slow; especially when one is working on a dissertation not about digital dualism. That said, papers are in progress, including ones with exciting co-authors, so the reason I am writing today is to give a first-pass on a framework that, I think, gets at much of the debate about digital dualism. It adds a little detail to “digital dualism versus augmented reality” by proposing “strong” and “mild” versions of each.* What I am asking here: Is this new categorization I’m proposing helpful? Do the new categories need different names? Are they cumbersome? Perhaps a whole different framework is needed?

To catch everyone up, let me provide some links for those not aware of “digital dualism” or the debates the term has inspired. I coined it here; how dualism is behind cyber-utopianism/dystopianism; the term’s first use in a peer-reviewed paper, on social movements; and my IRL Fetish essay is perhaps the deployment of digital dualism that I’m most proud of. David Banks, Zeynep Tufekci, Jeremy Antley, PJ Rey, PJ again, and too many others to list here have also joined the critique of digital dualism. And my critique has itself been counter-critiqued. I’ve responded to criticisms here, here, and here. Recently, observing this dialogue, Whitney Erin Boesel and Giorgio Fontana have worked to outline the issues on the table. Following Whitney’s call, let me try to patch some of the “hole” in our thinking about digital dualism.

The hole, or the confusion, has much to do with what exactly delineates dualistic and synthetic conceptualizations of the on and offline. I call Sherry Turkle a dualist yet she articulates how the on and offline interact. I claim and promote a synthetic perspective, yet I also claim the digital and physical are still very different. We use spatial language to talk about the digital and physical as different worlds, yet our experience of, say, Facebook, isn’t exactly like leaving our everyday lived reality. Right now, for the vast majority of writers, the relationship between the physical and digital looks like a big conceptual mess.**

There might be a simple solution to clean some of this mess, to take into account (but probably not solve) the various arguments being made: differentiating two flavors of both digital dualism and augmented reality. These categories should be thought of as “ideal types”, conceptual categories that are never perfectly realized in reality, but are useful to “think with.” Also, thinkers often and inconsistently move around inside these categories, which is itself a problem, and something that making these categories explicit might help solve.***

Strong Digital Dualism: The digital and the physical are different realities, have different properties, and do not interact.

Almost no one fits cleanly in this category all the time. Even cyberpunk fiction paradigmatic of digital dualism allows minimal interaction between, say, Zion and the Matrix. The usefulness of this category is for those who to critique digital dualism to recognize this category as largely a straw-argument. Appealing to this position as anything other than rare is a mistake regardless one’s position in this debate.

Mild Digital Dualism: The digital and physical are different realities, have different properties, and do interact.

When I critique digital dualism, it is usually this position. The most famous thinker I would place here is Sherry Turkle. Her “second self” demonstrates not one self with digital and physical components, but a second self, one that can influence and be influenced by a first self. A mild digital dualist does not need to maintain that the first and second self, or the on and offline, always interact, but just that they can interact. Both mild and strong dualisms have a zero-sum conceptualization of the on and offline: if you are offline, then you are not-online, and vice versa.

Mild Augmented Reality: The digital and physical are part of one reality, have different properties, and interact.

This is the position I argue from. The digital is seen as one flavor of information of many. And these different types of information, including the digital, have different properties and affordances. Interaction on Facebook is different than at a coffee shop, but both Facebook and the coffee shop inhabit one reality. And, of course, the many flavors of information interact. Both mild and strong synthetic perspectives do not have a zero-sum view of the digital and physical: reality is always some simultaneous combination of materiality and the many different types of information, digital included.

Strong Augmented Reality: The digital and physical are part of one reality and have the same properties.

That is, the digital and physical are the same thing, which precludes asking if they interact. This is a rare position, though people do sometimes land here, if only briefly. Sometimes those agreeable to theories that blur boundaries around technologies equate, say, humans with technology. This view claims that the differences between humans and technology or the on and offline are false. This is a perspective I disagree with as much as the variations of digital dualism; for instance, on January 25th, 2011, I was rooting for the protesters in Tahrir Square, not their phones.

Or, play this fun game:

Sometimes mild dualism and mild augmentation look very similar. Researcher A can view identity in the age of Facebook as two selves in constant and deep dialogue and Researcher B can see one self influenced differently by digitality and materiality, and the research might otherwise be very similar. For me, this is a best-case-scenario, where the disagreement is “merely” ontological and semantic but, in consequence, the research questions asked, the methods deployed, and the conclusions drawn are more alike than different.

However, remembering that research within each category can still look very different, mild dualism often means different questions are asked, methods used, and conclusions made as contrasted to a mild augmented project. Mild dualism is often used to demonstrate a second self still too detached from material bodies and offline existence. For instance, different than the best-case-scenario described above, some mild dualists will often claim that the first self influences the second self, but still carve out moments where this does not occur, where the first or second self is momentarily detached. The augmented perspective precludes this as even a possibility; instead, the on and offline are always in conversation, even if in different ways at different times. Further, mild dualists are far more likely to study, say, Facebook, by only looking at the site itself, a radically myopic methodology from the augmented perspective.

The big difference here is the basic dualist presupposition that one goes “on” and “off” line in some zero-sum fashion. As stated above, the augmented perspective rejects this unfortunate spatial vocabulary we’ve created and understands materiality as always interpenetrated by information of all varieties, of which ‘digital’ is only one.

An Example

I recently came across a short piece for the print edition of The Economist. While joining the important task of recognizing that the digital and physical interact, the author, Patrick Lane, describes the modern situation as a mild dualist:

But the opportunity would not exist had the physical and digital worlds not become tightly intertwined …

it also demonstrates the importance of physical location to today’s digital realm …

Today’s worker may leave the office physically but never digitally: he is attached to it with invisible tethers through his smartphone and his tablet …****

the physical realm also shapes the digital one …

In recent years there has been an explosion of investment in creating online representations of the real world …

The digital and the physical world are interacting ever more closely

Sounds like mild dualism: different worlds interacting. But then, the last line of the article is,

The digital and the physical are becoming one.

What to make of this? After taking great pains throughout the story to discuss the digital and physical as separate but interacting worlds, Lane concludes that they are “one.” In one line, it seems that Lane jumped from mild dualism to strong augmentation. These inconsistencies are prevalent across academic research and into less formal tech-writing, and is something I’d like to help resolve.

More important to me than convincing anyone of what the “correct” category to think within is getting these conceptual categories clear. From my perspective, the bigger problem than digital dualism is that people so often waffle back and forth across each of these categories, often within the same paragraph. I’d like for thinkers to be conceptually clear with respect to their very unit of analysis. Once we have our positions clear, we can begin discussing which stance best describes the realities we are studying.

Follow Nathan on Twitter: @nathanjurgenson

*I could create more than just four here, but categories can proliferate infinitely, causing a loss in clarity, so I want to be careful to only use them as needed.

**This is not to say others have not tried to untangle these theoretical knots in various ways, often weaving new ones in the process, as my first introduction with Actor Network Theory has begun to make clear. I’m still very new to ANT, and while I have not been convinced that it solves the dilemma here, I am too amateur with respect to the theory to make a convincing argument that it isn’t fruitful, and remain open to moving in this direction in the future.

***During the day I first posted this essay, I changed the word “worlds” to “realities” in the definitions of strong and mild dualisms in light of a good critique by Sarani Rangarajan.

****What’s with The Economist publishing weirdly sexist gendered terms? STOP THAT BECAUSE SEXISM, FEMINISM, AND IT’S 2012.