The Cyborgology Editors Nathan Jurgenson and PJ Rey are the guests on the latest Office Hours podcast. We chat about the Theorizing the Web 2011 conference we put on, as well as the Cyborgology blog. Listen here.

The Cyborgology Editors Nathan Jurgenson and PJ Rey are the guests on the latest Office Hours podcast. We chat about the Theorizing the Web 2011 conference we put on, as well as the Cyborgology blog. Listen here.

This post originally appeared on OWNI, 7 March, 2011.

“Robert, I am leaving you.” In the initial moments after, all Robert could do was replay those words in his head until all the tears he could muster had spilled from his broken heart. Once the shock settled, he could throw himself into the comfort of a bottle of beer – or harder alcohol depending on the situation – to drown out his sorrows. Yet the inevitable form of cleansing was obvious, as we’ve all been Robert – he needed to burn (or at least return to the original owner) the knick-knacks, photos, love letters, and the memories that were attached to those objects. He needed to reject the one who no longer wanted him. This is not an easy step to make, but once this purging has been accomplished then the relationship is truly over.

That was before…and like everything else, yes, it was better before. Now, Robert must also mange his failed love-life in the digital world. It is nothing groundbreaking that our lives are not just physical, but also virtual. So if we raise the question whether our digital accounts will affect the grieving process of friends and family after out death, the same inquiry can be applied to breakups. Social networks have permanently changed the situation, making breakups more painful. A US marketing agency tried to create “break up with your ex day” on the same day as Valentine’s Day: time to turn the page, unfollow, untag, block, and move on! Wise decision, but breaking digital connections are not the same as breaking ties in real life. The digital world constantly reminds the most desperate and nostalgic of their misfortunes.

Lucy* had been dumped, and was too quick to take the decision to cut off her torturer from her Facebook profile. “I blocked him to avoid being tempted to contact him on his status updates. I knew I would post something or send him a message. It’s childish, I know!” Skip to the hater category, a well-known classic in the breakup realm.

Facebook also expands the breakup problem to the ex’s friends and family. Lucy didn’t want to remove these people, as she found that too childish. She does have the option of using the chrome extension “Eternal Sunshine,” (named after the movie Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind that followed the difficulties of a couple trying to forget each other) allowing to hide unwanted people on Facebook without actually unfriending them. Obviously it is cowardly, but it’s less declarative and rude that the classic blocking methods. But Lucy didn’t use this option.

He didn’t restrict my access to his profile. It was horrible! For three or four months I was completely obsessed.

Lucy saw everything. The photos, the friends he added, the posts – everything was analyzed. She “hid” behind his wall, unable to resist the urge to click onto his profile to get her daily fix. “I had the need for three minutes. It’s like a drug: it’s unhealthy and adds nothing but more pain.” Every time she viewed his page, she was breaking the process of a normal recovery. Before Facebook, we would merely stop seeing people and over time become apathetic. “There was always that temptation of another hit, which results in another crash. With social networks, there is no cure. The wound is always reopened.”

If only poor Werther, who spent his days staring anxiously into the mountains needing to know everything about his beloved Charlotte, knew that actually knowing would not help (Facebook certainly proves this in modern times). Would there have been less suffering? Or would Twitter have turned this broken-hearted man into a control freak?

“Twitter is more vicious,” says Louis* who is struggling to return to the single life. As if Facebook is hard enough, Twitter is a completely different monster to tame. “You see everything. Just search for the person’s name and Twitter shows everything – what she tweeted, and who responded. It’s crazy. For a long time I logged on several times a day. It was impossible to resist the craving. I continue doing it even though I know I’ll feel horrible.” Poor Louis. The digital world is eating away at his tiny bit of control, and his browsing history is always there to remind him of his weakness. “I feel stupid when I systematically erase the history – because I pretend I’m looking at the profile page for the first time, and it eases the pain.” A bit of a control freak? Maybe just a jilted lover who can’t turn the page and is further drawn into the past with the stalking possibilities provided by Twitter, as facing the sudden silence is just too much.

If we believe that digital networks are only an extension of our social life and it just completes the interactions, in the case of a breakup it’s evident that this theory fails to cover the circumstance. ForAntonio Casilli (a researcher and author of the book Liaisons numériques) the two forms of social links are different: “Before the Internet, if a person was able to contact his ex after a breakup, then it reaffirmed the strong link that once existed between these two people. With the Internet, this link is not necessarily revived. We can continue to interact with this person, but on the basis of a fragmented signal and thus a much weaker link. The stalker is content with his passive observations. This distinction between strong and weak links may be more effective in articulating the dynamics of these relationships.”

In the case of Lucy and Louis, interpretation is the key element. Antonio Casili explains:

It’s exactly like when we analyse the actions of someone. With social networks, we must be wary of the false pretense that we are objective. There is the same type of projection at work, as we are constantly trying to assign an intent or sentiment to other people.

Before the era of super connectivity, when a breakup went south it was still possible (in extreme cases) to spy on the person who abandoned you. Such is the traditional definition of stalking: wait at the exit of their office and apartment. This is what Rob did in the book High Fidelity. In this case there was the risk of appearing like a freak. Today, generation Y can indulge in their perverse behavior without fear of crossing society’s taboo. From the safety of their homes, the singleton can spy on multiple profiles. If one has a smartphone, he can even conveniently stalk his ex on his way to work. There is nobody to stop these delinquent actions and no police can intervene in this unhealthy addiction. Nobody will know about this secret obsession.

We are free to indulge in self-inflicted pain. “I know that her new boyfriend is on Twitter. I try with all my willpower not to look at his timeline. It’s hard to know that you can follow their relationship. It’s pretty painful. It’s because of Twitter I know who replaced me.” Louis is playing with fire, and once burned decides to treat his wound with gasoline and put his hand back into the flames. Besides strength of character issues, he has no solution for how to stop torturing himself. The timeline is in the public domain, accessible with one click. “Before we could naturally lose touch with an ex. It’s a shame.” Louis is not finished with his pyromaniac impulses. For Antonio Casilli, it is not simply “an extension of relationship distress.”

It is the same thing in reality but the mode is different. There is a very strong desire, and the Internet permits people to act on these feelings. The web changes the rules in the game of love, to take Meetic’s slogan.

The more vicious and desperate can take their heartbreak even further on Spotify or LastFm. “I started by removing her playlist from my account,” said Joseph after he was rejected, but then a morbid curiosity overtook him. “I was regularly on her profile to know the artist and songs she was listening to the most. It was a disturbing pseudo relationship that exhilarated me. When she was sad, that made me happy. When the titles were more catchy and joyful, it had the opposite effect on me.” It was an extreme and sadomasochistic form of stalking.

Facebook, Twitter, Spotify and Foursquare reinforces the links that need to be severed in the event of a breakup. Even if real communication is not replaced by virtual, the latter does maintain a pretense of the relationship. Antonio Casillas advises that there needs to be two breaks: “The two breaks are intertwined. The first is the actual breakup, which should be in person or over the telephone. The second break is the severing of online ties: Blocking the person on MSN, defriending on Facebook, etc…The third phase is to stop viewing the ex’s profile page. It is a voluntary act to search for information, yet in our environment full of digital traces sometimes these bits of information come to us.

And for those who absolutely need to know, a few crafty designers created a Facebook application that notifies you immediately when your ex is back on the market – definitely not a tool to help with the moving on stage. The breakup notifier attracted nearly 3 million people before being deleted at the request of Facebook. Dan Loeenhers, the creator of this bizarre application, asserts that it was for the user’s benefit. “It’s really a practical thing. If you’re going to refresh someone’s page 20 times a day, why not have an alert on it?” Why not? Now you just have to spend your time frantically refreshing your mail. Very practical.

* The names have been modified.

Google Maps has a new tool to help the consumers of its popular maps also be producers. Users-generated improvements will be a benifit to many, but probably most to Google itself. While the Google video below paints all of this in light of personal or civic empowerment (“leave your mark”), we should also understand that this move towards us becoming “prosumers” of these maps is also about the company taking advantage of our free labor in hopes of earning greater profits. Does that bother anyone?

Google Maps has a new tool to help the consumers of its popular maps also be producers. Users-generated improvements will be a benifit to many, but probably most to Google itself. While the Google video below paints all of this in light of personal or civic empowerment (“leave your mark”), we should also understand that this move towards us becoming “prosumers” of these maps is also about the company taking advantage of our free labor in hopes of earning greater profits. Does that bother anyone?

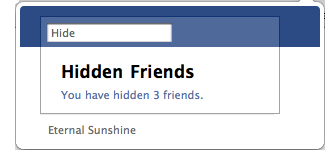

Shepard Fairey, that designer most famous for creating (stealing?) the iconic Obama image, has designed the cover for the new edition of Marshall McLuhan’s famous book, The Medium is the Massage. Fairey is known for creating art that often makes reference to the way propaganda is used by the powerful to control the masses into obeying. In fact, Fairey’s famous “OBEY” graphic is a reference to John Carpenter’s brilliant 1988 film about consumer culture, They Live (plot: with the help of special sunglasses, advertisements are revealed as actually reading, “obey,” “consume” and so on). Be it advertising, print, television or social media, McLuhan’s points remain important.

Shepard Fairey, that designer most famous for creating (stealing?) the iconic Obama image, has designed the cover for the new edition of Marshall McLuhan’s famous book, The Medium is the Massage. Fairey is known for creating art that often makes reference to the way propaganda is used by the powerful to control the masses into obeying. In fact, Fairey’s famous “OBEY” graphic is a reference to John Carpenter’s brilliant 1988 film about consumer culture, They Live (plot: with the help of special sunglasses, advertisements are revealed as actually reading, “obey,” “consume” and so on). Be it advertising, print, television or social media, McLuhan’s points remain important.

“Electrical Information Devices for universal, tyrannical womb-to-tomb surveillance are causing a very serious dilemma between our claim to privacy and the community’s need to know”.

I am working on a dissertation about self-documentation and social media and have decided to take on theorizing the rise of faux-vintage photography (e.g., Hipstamatic, Instagram). From May 10-12, 2011, I posted a three part essay. This post combines all three together.

Part I: Instagram and Hipstamatic

Part II: Grasping for Authenticity

Part III: Nostalgia for the Present

Part I: Instagram and Hipstamatic

This past winter, during an especially large snowfall, my Facebook and Twitter streams became inundated with grainy photos that shared a similarity beyond depicting massive amounts of snow: many of them appeared to have been taken on cheap Polaroid or perhaps a film cameras 60 years prior. However, the photos were all taken recently using a popular set of new smartphone applications like Hipstamatic or Instagram. The photos (like the one above) immediately caused a feeling of nostalgia and a sense of authenticity that digital photos posted on social media often lack. Indeed, there has been a recent explosion of retro/vintage photos. Those smartphone apps have made it so one no longer needs the ravages of time or to learn Photoshop skills to post a nicely aged photograph.

In this essay, I hope to show how faux-vintage photography, while seemingly banal, helps illustrate larger trends about social media in general. The faux-vintage photo, while getting a lot of attention in this essay, is merely an illustrative example of a larger trend whereby social media increasingly force us to view our present as always a potential documented past. But we have a ways to go before I can elaborate on that point. Some technological background is in order.

The first very popular app that made your photographs instantly retro was Hipstamatic app. Instagram is even more powerful with its selection of multiple “filters,” that is, different flavors of vintage (a few not-so-vintage filters are available, too). Instagram also features a popular social networking layer that allows users to contribute and view a stream of Instagram photos with “friends.” Other retro photography applications are available as well.

What do these apps do? Among other things, they fade the image (especially at the edges), adjust the contrast and tint, over- or under-saturate the colors, blur areas to exaggerate a very shallow depth of field, add simulated film grain, scratches and other imperfections and so on. And, importantly for the next post, the photos are often made to mimic being printed on real, physical photo paper. And many of our Facebook, Tumblr, Twitter, etc. streams have become the home to one of these vintage-looking photos after another.

Why Faux-Vintage Now?

This trend was made possible due to the rise of smartphones because smartphone photography has at least three important differences from the previous (and increasingly endangered) point-and-shoot digital cameras: (1) your smartphone is more likely to be on you all the time, even while sleeping, than was even the most portable point-and-shoot; (2) the smart phone camera exists as part of a powerful computer-software ecosystem comprised of a series of applications; and (3) the smartphone is typically connected to the Internet in more ways and more often than previous cameras were. Thus, the photos you take are more likely to be social (opposed to for personal consumption only) because the camera is now always with you in social situations, and, most importantly, the device is connected to the web and exists within a series of other apps on your smartphone that are often capable of delivering content to various social media. Beyond being social, the applications make it far easier to apply different filters to photos than did point-and-shoot cameras or using photo editing software on your computer.

But the question I am asking with this essay is not just about the rise of digitally manipulated social photography, but why these digitally manipulated photos showing up in our social media streams are manipulated specifically to look vintage. Why do so many of us prefer to take, share and view these faux-aged photos?

Is Picture-Quality the Reason?

Perhaps, as another blogger noted, it is the low quality of phone cameras that has lead to the rise of faux-vintage. Maybe the current quality of smartphone cameras tends to produce stale photographs which are then made more interesting when given a faux-vintage filter? Photographers have long known that, depending on the situation, a gritty photo can be as good as or better than a technically perfect shot, and now everyone with a smartphone can take an interesting picture with just one additional press of a button. But, this explanation does little to explain why we equate vintage with interesting in the first place. [Also, many current smartphone cameras are of high quality].

Poets and Scribes?

Another reason for the rise of faux-vintage photography might be that these apps allow us to be more creative with our photos. Susan Sontag in the wonderful On Photography discusses how photography is always both the capturing of truth as well as a subjective creation. In this sense, when taking a photograph we are at once both poets and scribes; a point that I have used to describe our self-documentation on social media: we are both telling the truth about our lives as scribes, but always doing so creatively like poets. So, if “photography is not only about remembering, it is [also] about creating,” then the rise of smartphones and photo apps have democratized the tools to create photos that emphasize art, not just truth. But, again, this explanation would only explain why we might want to manipulate photos in the first place. It does not explain why so many of us have so often chosen to manipulate them into looking specifically retro/vintage.

Part II: Grasping for Authenticity

So far I have described what faux-vintage photography is and noted that it is a new trend, comes primarily from smartphones and has proliferated on social media sites like Facebook, Tumblr and others. However, the important question remains: why this massive popularity of faux-vintage photographs?

What I want to argue is that the rise of the faux-vintage photo is an attempt to create a sort of “nostalgia for the present,” an attempt to make our photos seem more important, substantial and real. We want to endow the powerful feelings associated with nostalgia to our lives in the present. And, ultimately, all of this goes well beyond the faux-vintage photo; the momentary popularity of the Hipstamatic-style photo serves to highlight the larger trend of our viewing the present as increasingly a potentially documented past. In fact, the phrase “nostalgia for the present” is borrowed from the great philosopher of postmodernism, Fredric Jameson, who states that “we draw back from our immersion in the here and now […] and grasp it as a kind of thing.”*

The term “nostalgia” was coined more than 300 years ago to describe the medical condition of severe, sometimes lethal, homesickness. By the 19th century the word morphs from a physical to a psychological descriptor, not just about the longing of a place, but also a longing for a time past that, except through reminders, one can never return to. Indeed, this is Marcel Proust’s favorite topic: the ways in which sensory stimuli have great power to invoke overwhelmingly strong feelings and vivid memories of the past; precisely the nostalgic feelings that faux-vintage photos seek to invoke.

Faux-Physicality as Augmented Reality

One important way in which the digital photo does this is by looking like it is not a digital photo at all. For many, and especially those using faux-vintage apps, photography is primarily experienced in the digital form: snapped on a digital camera and stored and shared via digital albums on computers and websites like Facebook. But just as the rise and proliferation of the mp3 is coupled with the resurgence of vinyl, there is a similar reclaiming of the aesthetic of the physical photo. Physicality, with its weight, smell and tactile interaction, grants a significance that bits have not (yet) achieved. The quickest way to invoke nostalgia for a time past with a photograph is to invoke the properties of the physical, which is done by mimicking the ravages of time through fading, simulated film grain and scratches as well as the addition of what appears to be photo-paper or Polaroid borders around the image.

This follows the trend of what I have labeled “augmented reality”: the fact that physical and digital are increasingly imploding into each other. And by making our digital photos appear physical, we are attempting to purchase the cachet and importance that physicality imparts. I’ve noted in the past this trend to endow the physical with a special importance. I commented on the bias to view physical books as more “deep” than digital text. I also critiqued those who label digital activism “slacktivism” and those who view digital communication as inherently shallow. Why would we grant the physical photo special importance?

This follows the trend of what I have labeled “augmented reality”: the fact that physical and digital are increasingly imploding into each other. And by making our digital photos appear physical, we are attempting to purchase the cachet and importance that physicality imparts. I’ve noted in the past this trend to endow the physical with a special importance. I commented on the bias to view physical books as more “deep” than digital text. I also critiqued those who label digital activism “slacktivism” and those who view digital communication as inherently shallow. Why would we grant the physical photo special importance?

Perhaps the answer is because the physical photograph was scarce. Producing a photo took longer and cost more money prior to the advent of digital photography. This is one of the main differences between atoms and bits: the former is scarce and the later is abundant; something I have written about before. That an old photo was taken and has survived grants it an authority that the equivalent digital photo taken today cannot achieve. In any case, that the faux-vintage photograph aspires to physicality is only part of why they have become so massively popular.

Nostalgia and Authenticity

I submit that we have chosen to create and view faux-vintage photos because they seem more authentic and real. One does not need to be consciously aware of this when choosing the filter, hitting the “like” button on Facebook or reblogging on Tumblr. We have associated authenticity with the style of a vintage photo because, previously, vintage photos were actually vintage. They stood the test of time, they described a world past, and, as such, they earned a sense of importance.

People are quite aware of the power of vintage and retro as carriers of authenticity. Sharon Zukin’s book Naked City expertly describes the recent gentrification of inner cities as the quest for authenticity, often in the form of grit and decay. For those born in the plastic, inauthentic world of suburban Disneyfied and McDonaldized America, there has been a cultural obsession with decay (“decay porn”) and a search for authentic reality in our simulated world (as Jean Baudrillard might say).

The faux-vintage photos populating our social media streams share a similar quality with the inner-city Brooklyn neighborhood rich with authentic grit: they conjure authenticity and real-ness in the age of simulation and the vast proliferation of digital images. And, in this way, the Hipstamatic photo places yourself and your present into the context of the past, the authentic, the important and the real.

But, of course, unlike urban grit or the rarity of an expensive antique, the vintage-ness of a Hipstamatic or Instagram photo is simulated (the faux in faux-vintage). We all know quite well that these photos are not really aged with time but instead by an app. These are self-aware simulations (perhaps the self-awareness is the hipster in Hipstamatic). The faux-vintage photo is more similar to a fake 1950’s diner built many decades later. They are Main St. in Disney world or the fake checkered cab in the New York, New York hotel and casino complex in Las Vegas. These are all simulations attempting to make people nostalgic for a time past. Consistent with Baudrillard’s description of simulations, photos in their Hipstamatic form have become more vintage than vintage; they exaggerate the qualities of the idea of what it is to be vintage and are therefore hyper-vintage.

The very thing that a faux-vintage photo provides, authenticity, is thus negated by the fact that it is a simulation. However, this fact does preclude these photos conjuring feelings of nostalgia and authenticity because what is being referenced is not “the vintage” but “the idea of the vintage,” similar to the simulated diner, modern checkered-cab or Disney Main St.; all hyper-real versions of something else and all quite capable of causing and exploiting feelings of nostalgia. Therefore, simply being aware that the authenticity Hipstamatic purchases is simulated does disqualify the faux-vintage photo from entering into the economy of the real and authentic.

Part III: Nostalgia for the Present

The rise of faux-vintage photography demonstrates a point that can be extrapolated to documentation on social media writ large: social media users have become always aware of the present as a potential document to be consumed by others. Facebook fixates the present as always a future past. Be it through status updates on Twitter, geographical check-ins on Foursquare, reviews on Yelp, those Instagram photos or all of the other self-documentation possibilities afforded to us by Facebook, we view our world more than ever before through what I like to call “documentary vision.”

Documentary vision is kind of like the “camera eye” photographers develop when, after taking many photos, they begin to see the world as always a potential photo even when not holding the camera at all. The habit of the photographer involuntarily framing and composing the world has become a metaphor for those trained to document using social media. The explosion of ubiquitous self-documentation possibilities, and the audience for our documents that social media promises, has positioned us to live life in the present with the constant awareness of how it will be perceived as having already happened. We come to see what we do as always a potential document, imploding the present with the past, and ultimately making us nostalgic for the here and now. And there is no better paradigmatic example for this view of the present as always a potential documented past than the faux-vintage photo (why I have chosen this as a topic for essay). The faux-vintage photo asks the viewer to suspend disbelief about the authenticity of the simulated nostalgia and to see the photo–and who and whatever is in it–as being authentic and important by referencing at least the idea of the past. While, technically, all photographs, indeed all documentation, conjure the past, the faux-vintage photograph serves to vividly underscore and make even more clear our efforts to display our lives in the present as already a past to feel nostalgic for.

And there is no better paradigmatic example for this view of the present as always a potential documented past than the faux-vintage photo (why I have chosen this as a topic for essay). The faux-vintage photo asks the viewer to suspend disbelief about the authenticity of the simulated nostalgia and to see the photo–and who and whatever is in it–as being authentic and important by referencing at least the idea of the past. While, technically, all photographs, indeed all documentation, conjure the past, the faux-vintage photograph serves to vividly underscore and make even more clear our efforts to display our lives in the present as already a past to feel nostalgic for.

The faux-vintage photograph is self-aware of itself as document. If regular photos placed on Facebook walls document that we exist, the faux-vintage photo is this but also more than this: it is also a reference to documentation itself. This double document–a document of documentation–becomes further proof that we are here and we exist. The rise of faux-vintage photographs, snapped on smartphones and shared via social media, is centrally an existential move that is deployed because conjuring the past creates a sense of nostalgia and authenticity.

But the ultimate irony is that while these tools, just like all of social media, help us reinforce to ourselves and others that we are real and authentic, but they do this by simultaneously divorcing us to some degree from experiencing our present in the here and now. Think of a time when you took a trip holding a camera and then think of when you did the same without the camera; most of us have probably traveled both with and without a camera in our hands and we know the experience is at least slightly different; some might claim radically different. With so many documentation possibilities (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Yelp, Foursquare and so on), we are always, both literally and metaphorically, living with the camera in our hands. When discovering a new bar or a great slice of pizza we might think of posting a review on Yelp; when overhearing a funny conversation we might think to tweet it; when hanging out with friends we might create a status update for Facebook; and when at a concert we might find ourselves distracted by needing to take and post a photo of the event as it happens. When the breakfast I made the other week looked especially delicious, I posted a photo of it before even taking a bite.

My larger dissertation project will be to explore these points and demonstrate specifically how this newly expanded documentary vision potentially changes what we do. Does knowing that you will check in on Foursquare at least slightly influence what restaurant you’ll choose to eat at? In what other ways is our online documentation not just a reflection of what we do but also sometimes (or always?) a cause? To go straight to the extreme case, I once overheard a young inebriated woman on the subway around 2am state that “the real world is where you take pictures for Facebook.” She was, I thought, the smartest person on that train.

What Will Become of the Faux-Vintage Photo?

Let me conclude this all by coming back to faux-vintage photos specifically. I think they might be a passing fad.

Let me conclude this all by coming back to faux-vintage photos specifically. I think they might be a passing fad.

Faux-vintage photos devalue and exhaust their own sense of authenticity, which portends their disappearance because, as I described in part II, authenticity is the very currency by which they have become popular; there is an inflation as a result of printing too much currency of the real. For instance, the faux-vintage photo will no longer be able to conjure the importance associated with physicality (another point made in part II) if the vintage look begins to be more closely associated with smartphones than old photos. The novelty begins to wear off and the nostalgia fades away.

Most damning for Hipstamatic and Instagram is that these apps tend to make everyone’s photos look similar. In an attempt to make oneself look distinct and special through the application of vintage-producing filters, we are trending towards photos that look the same. The Hipstamatic photo was new and interesting, is currently a fad, and it will come to (or, already has?) look too posed, too obvious, and trying too hard (especially if the parents of the current users start to post faux-vintage photos themselves).

To be clear, photographic techniques like saturation, fading, vignetting and others are not essentially good or bad (for instance, I love these faux-vintage shots). But when so widely used they seem less like an artistic choice and more as if they are merely following a trend (what Baudrillard called the “logic of fashion”). The ironic fate that extinguishes so many trends built on suggesting and exploiting authenticity is that their very popularity extinguishes that which made them popular.

The inevitable decline (but not full disappearance) of the faux-vintage photo will be our collective decision that the style is beginning to appear increasingly posed, contrived and passé, and thus negating the feelings of authenticity that were the very reason we liked them in the first place. Another retro-looking photo of a sunny country road, a dandelion, or your feet?

*quote is from page 284 of Jameson’s Postmodernism: Or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham: Duke University Press, 1991.

Follow Nathan on Twitter: @nathanjurgenson

This essay has been translated into French here.

Also: Faux-Vintage Afghanistan and the Nostalgia for War.

Credit for the snowstorm image: http://tballardbrown.tumblr.com/

Credit for the Disney castle image: http://www.flickr.com/photos/chel1974/4578467229/in/photostream/

Credit for the Hipstamatic photogrid: http://www.myglasseye.net/

Credit for the final image, from: http://www.etsy.com/listing/61906957/photographic-memory-print?ref=pr_shop

I am working on a dissertation about self-documentation and social media and have decided to take on theorizing the rise of faux-vintage photography (e.g., Hipstamatic, Instagram). To start fleshing out ideas, I am doing a three-part series on this blog: part one was posted Tuesday (“Hipstamatic and Instagram”) and part two yesterday (“Grasping for Authenticity”). This is the last installment.

With more than two million users each, Hipstamatic and Instagram have ushered a wave of simulated retro photographs that have populated our social media streams. Even a faux-vintage video application is gaining popularity. The first two posts in this series described what faux-vintage photography is, its technical facilitators and attempted to explain at least one main reason behind its explosive popularity. When we create an instant “nostalgia for the present” by sharing digital photos that look old and often physical, we are trying to capture for our present the authenticity and importance vintage items possess. In this final post, I want to argue that faux-vintage photography, a seemingly mundane and perhaps passing trend, makes clear a larger point: social media, in its proliferation of self-documentation possibilities, increasingly positions our present as always a potential documented past.

Nostalgia for the Present

The rise of faux-vintage photography demonstrates a point that can be extrapolated to documentation on social media writ large: social media users have become always aware of the present as a potential document to be consumed by others. Facebook fixates the present as always a future past. Be it through status updates on Twitter, geographical check-ins on Foursquare, reviews on Yelp, those Instagram photos or all of the other self-documentation possibilities afforded to us by Facebook, we view our world more than ever before through what I like to call “documentary vision.”

Documentary vision is kind of like the “camera eye” photographers develop when, after taking many photos, they begin to see the world as always a potential photo even when not holding the camera at all. The habit of the photographer involuntarily framing and composing the world has become a metaphor for those trained to document using social media. The explosion of ubiquitous self-documentation possibilities, and the audience for our documents that social media promises, has positioned us to live life in the present with the constant awareness of how it will be perceived as having already happened. We come to see what we do as always a potential document, imploding the present with the past, and ultimately making us nostalgic for the here and now. And there is no better paradigmatic example for this view of the present as always a potential documented past than the faux-vintage photo (why I have chosen this as a topic for essay). The faux-vintage photo asks the viewer to suspend disbelief about the authenticity of the simulated nostalgia and to see the photo–and who and whatever is in it–as being authentic and important by referencing at least the idea of the past. While, technically, all photographs, indeed all documentation, conjure the past, the faux-vintage photograph serves to vividly underscore and make even more clear our efforts to display our lives in the present as already a past to feel nostalgic for.

And there is no better paradigmatic example for this view of the present as always a potential documented past than the faux-vintage photo (why I have chosen this as a topic for essay). The faux-vintage photo asks the viewer to suspend disbelief about the authenticity of the simulated nostalgia and to see the photo–and who and whatever is in it–as being authentic and important by referencing at least the idea of the past. While, technically, all photographs, indeed all documentation, conjure the past, the faux-vintage photograph serves to vividly underscore and make even more clear our efforts to display our lives in the present as already a past to feel nostalgic for.

The faux-vintage photograph is self-aware of itself as document. If regular photos placed on Facebook walls document that we exist, the faux-vintage photo is this but also more than this: it is also a reference to documentation itself. This double document–a document of documentation–becomes further proof that we are here and we exist. The rise of faux-vintage photographs, snapped on smartphones and shared via social media, is centrally an existential move that is deployed because conjuring the past creates a sense of nostalgia and authenticity.

But the ultimate irony is that while these tools, just like all of social media, help us reinforce to ourselves and others that we are real and authentic, but they do this by simultaneously divorcing us to some degree from experiencing our present in the here and now. Think of a time when you took a trip holding a camera and then think of when you did the same without the camera; most of us have probably traveled both with and without a camera in our hands and we know the experience is at least slightly different; some might claim radically different. With so many documentation possibilities (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Yelp, Foursquare and so on), we are always, both literally and metaphorically, living with the camera in our hands. When discovering a new bar or a great slice of pizza we might think of posting a review on Yelp; when overhearing a funny conversation we might think to tweet it; when hanging out with friends we might create a status update for Facebook; and when at a concert we might find ourselves distracted by needing to take and post a photo of the event as it happens. When the breakfast I made the other week looked especially delicious, I posted a photo of it before even taking a bite.

My larger dissertation project will be to explore these points and demonstrate specifically how this newly expanded documentary vision potentially changes what we do. Does knowing that you will check in on Foursquare at least slightly influence what restaurant you’ll choose to eat at? In what other ways is our online documentation not just a reflection of what we do but also sometimes (or always?) a cause? To go straight to the extreme case, I once overheard a young inebriated woman on the subway around 2am state that “the real world is where you take pictures for Facebook.” She was, I thought, the smartest person on that train.

What Will Become of the Faux-Vintage Photo?

Let me conclude this all by coming back to faux-vintage photos specifically. I think they might be a passing fad.

Let me conclude this all by coming back to faux-vintage photos specifically. I think they might be a passing fad.

Faux-vintage photos devalue and exhaust their own sense of authenticity, which portends their disappearance because, as I described in part II, authenticity is the very currency by which they have become popular; there is an inflation as a result of printing too much currency of the real. For instance, the faux-vintage photo will no longer be able to conjure the importance associated with physicality (another point made in part II) if the vintage look begins to be more closely associated with smartphones than old photos. The novelty begins to wear off and the nostalgia fades away.

Most damming for Hipstamatic and Instagram is that these apps tend to make everyone’s photos look similar. In an attempt to make oneself look distinct and special through the application of vintage-producing filters, we are trending towards photos that look the same. The Hipstamatic photo was new and interesting, is currently a fad, and it will come to (or, already has?) look too posed, too obvious, and trying too hard (especially if the parents of the current users start to post faux-vintage photos themselves).

To be clear, photographic techniques like saturation, fading, vignetting and others are not essentially good or bad (for instance, I love these faux-vintage shots). But when so widely used they seem less like an artistic choice and more as if they are merely following a trend (what Baudrillard called the “logic of fashion”). The ironic fate that extinguishes so many trends built on suggesting and exploiting authenticity is that their very popularity extinguishes that which made them popular.

The inevitable decline (but not full disappearance) of the faux-vintage photo will be our collective decision that the style is beginning to appear increasingly posed, contrived and passé, and thus negating the feelings of authenticity that were the very reason we liked them in the first place. Another retro-looking photo of a sunny country road, a dandelion, or your feet?

check out part I and part II of this essay

I am working on a dissertation about self-documentation and social media and have decided to take on theorizing the rise of faux-vintage photography (e.g., Hipstamatic, Instagram). I want to start fleshing out ideas and will do so with a three-part series on this blog: I posted part one yesterday (“Hipstamatic and Instagram”) and tomorrow I will post the third and final part (“Nostalgia for the Present”). [Update: Read the full essay here.]

If you use social media then you probably have noticed the recent proliferation of faux-vintage photography, often the product of smartphone applications such as Hipstamatic and Instagram. I describe in part I of this essay posted yesterday what faux-vintage photography is and noted that it is a new trend, comes primarily from smartphones and has proliferated on social media sites like Facebook, Tumblr and others. However, the important question remains: why this massive popularity of faux-vintage photographs? I will tackle this question today, and in part III tomorrow, will conclude that the rise, and potential fall, of faux-vintage photography illustrates larger points about social media in general.

What I want to argue is that the rise of the faux-vintage photo is an attempt to create a sort of “nostalgia for the present,” an attempt to make our photos seem more important, substantial and real. We want to endow the powerful feelings associated with nostalgia to our lives in the present. And, ultimately, all of this goes well beyond the faux-vintage photo; the momentary popularity of the Hipstamatic-style photo serves to highlight the larger trend of our viewing the present as increasingly a potentially documented past. In fact, the phrase “nostalgia for the present” is borrowed from the great philosopher of postmodernism, Fredric Jameson, who states that “we draw back from our immersion in the here and now […] and grasp it as a kind of thing.”*

The term “nostalgia” was coined more than 300 years ago to describe the medical condition of severe, sometimes lethal, homesickness. By the 19th century the word morphs from a physical to a psychological descriptor, not just about the longing of a place, but also a longing for a time past that, except through reminders, one can never return to. Indeed, this is Marcel Proust’s favorite topic: the ways in which sensory stimuli have great power to invoke overwhelmingly strong feelings and vivid memories of the past; precisely the nostalgic feelings that faux-vintage photos seek to invoke.

Faux-Physicality as Augmented Reality

One important way in which the digital photo does this is by looking like it is not a digital photo at all. For many, and especially those using faux-vintage apps, photography is primarily experienced in the digital form: snapped on a digital camera and stored and shared via digital albums on computers and websites like Facebook. But just as the rise and proliferation of the mp3 is coupled with the resurgence of vinyl, there is a similar reclaiming of the aesthetic of the physical photo. Physicality, with its weight, smell and tactile interaction, grants a significance that bits have not (yet) achieved. The quickest way to invoke nostalgia for a time past with a photograph is to invoke the properties of the physical, which is done by mimicking the ravages of time through fading, simulated film grain and scratches as well as the addition of what appears to be photo-paper or Polaroid borders around the image.

This follows the trend of what I have labeled “augmented reality”: the fact that physical and digital are increasingly imploding into each other. And by making our digital photos appear physical, we are attempting to purchase the cachet and importance that physicality imparts. I’ve noted in the past this trend to endow the physical with a special importance. I commented on the bias to view physical books as more “deep” than digital text. I also critiqued those who label digital activism “slacktivism” and those who view digital communication as inherently shallow. Why would we grant the physical photo special importance?

Perhaps the answer is because the physical photograph was scarce. Producing a photo took longer and cost more money prior to the advent of digital photography. This is one of the main differences between atoms and bits: the former is scarce and the later is abundant; something I have written about before. That an old photo was taken and has survived grants it an authority that the equivalent digital photo taken today cannot achieve. In any case, that the faux-vintage photograph aspires to physicality is only part of why they have become so massively popular.

Nostalgia and Authenticity

I submit that we have chosen to create and view faux-vintage photos because they seem more authentic and real. One does not need to be consciously aware of this when choosing the filter, hitting the “like” button on Facebook or reblogging on Tumblr. We have associated authenticity with the style of a vintage photo because, previously, vintage photos were actually vintage. They stood the test of time, they described a world past, and, as such, they earned a sense of importance.

People are quite aware of the power of vintage and retro as carriers of authenticity. Sharon Zukin’s book Naked City expertly describes the recent gentrification of inner cities as the quest for authenticity, often in the form of grit and decay. For those born in the plastic, inauthentic world of suburban Disneyfied and McDonaldized America, there has been a cultural obsession with decay (“decay porn”) and a search for authentic reality in our simulated world (as Jean Baudrillard might say).

The faux-vintage photos populating our social media streams share a similar quality with the inner-city Brooklyn neighborhood rich with authentic grit: they conjure authenticity and real-ness in the age of simulation and the vast proliferation of digital images. And, in this way, the Hipstamatic photo places yourself and your present into the context of the past, the authentic, the important and the real.

But, of course, unlike urban grit or the rarity of an expensive antique, the vintage-ness of a Hipstamatic or Instagram photo is simulated (the faux in faux-vintage). We all know quite well that these photos are not really aged with time but instead by an app. These are self-aware simulations (perhaps the self-awareness is the hipster in Hipstamatic). The faux-vintage photo is more similar to a fake 1950’s diner built many decades later. They are Main St. in Disney world or the fake checkered cab in the New York, New York hotel and casino complex in Las Vegas. These are all simulations attempting to make people nostalgic for a time past. Consistent with Baudrillard’s description of simulations, photos in their Hipstamatic form have become more vintage than vintage; they exaggerate the qualities of the idea of what it is to be vintage and are therefore hyper-vintage.

The very thing that a faux-vintage photo provides, authenticity, is thus negated by the fact that it is a simulation. However, this fact does preclude these photos conjuring feelings of nostalgia and authenticity because what is being referenced is not “the vintage” but “the idea of the vintage,” similar to the simulated diner, modern checkered-cab or Disney Main St.; all hyper-real versions of something else and all quite capable of causing and exploiting feelings of nostalgia. Therefore, simply being aware that the authenticity Hipstamatic purchases is simulated does disqualify the faux-vintage photo from entering into the economy of the real and authentic.

What all this hints at– and this will be the topic for the third and final part of this essay tomorrow– is that Hipstamatic and Instagram are merely good examples of a larger trend inherent to all social media: that the rapid proliferation of self-documentation possibilities makes us increasingly live our present as a potential documented past.

*quote is from page 284 of Jameson’s Postmodernism: Or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham: Duke University Press, 1991.

Follow Nathan on Twitter: @nathanjurgenson

I am working on a dissertation about self-documentation and social media and have decided to take on theorizing the rise of faux-vintage photography (e.g., Hipstamatic, Instagram). I want to start fleshing out ideas and will do so with a three-part series on this blog: I will post part two (“Grasping for Authenticity”) tomorrow and part three (“Nostalgia for the Present”) Thursday.

This past winter, during an especially large snowfall, my Facebook and Twitter streams became inundated with grainy photos that shared a similarity beyond depicting massive amounts of snow: many of them appeared to have been taken on cheap Polaroid or perhaps a film cameras 60 years prior. However, the photos were all taken recently using a popular set of new smartphone applications like Hipstamatic or Instagram. The photos (like the one above) immediately caused a feeling of nostalgia and a sense of authenticity that digital photos posted on social media often lack. Indeed, there has been a recent explosion of retro/vintage photos. Those smartphone apps have made it so one no longer needs the ravages of time or to learn Photoshop skills to post a nicely aged photograph.

In this essay, I hope to show how faux-vintage photography, while seemingly banal, helps illustrate larger trends about social media in general. The faux-vintage photo, while getting a lot of attention in this essay, is merely an illustrative example of a larger trend whereby social media increasingly force us to view our present as always a potential documented past. But we have a ways to go before I can elaborate on that point (see parts II and especially III of this essay). Some technological background is in order.

The first very popular app that made your photographs instantly retro was Hipstamatic app. Instagram is even more powerful with its selection of multiple “filters,” that is, different flavors of vintage (a few not-so-vintage filters are available, too). Instagram also features a popular social networking layer that allows users to contribute and view a stream of Instagram photos with “friends.” Other retro photography applications are available as well.

What do these apps do? Among other things, they fade the image (especially at the edges), adjust the contrast and tint, over- or under-saturate the colors, blur areas to exaggerate a very shallow depth of field, add simulated film grain, scratches and other imperfections and so on. And, importantly for the next post, the photos are often made to mimic being printed on real, physical photo paper. And many of our Facebook, Tumblr, Twitter, etc. streams have become the home to one of these vintage-looking photos after another.

Why Faux-Vintage Now?

This trend was made possible due to the rise of smartphones because smartphone photography has at least three important differences from the previous (and increasingly endangered) point-and-shoot digital cameras: (1) your smartphone is more likely to be on you all the time, even while sleeping, than was even the most portable point-and-shoot; (2) the smart phone camera exists as part of a powerful computer-software ecosystem comprised of a series of applications; and (3) the smartphone is typically connected to the Internet in more ways and more often than previous cameras were. Thus, the photos you take are more likely to be social (opposed to for personal consumption only) because the camera is now always with you in social situations, and, most importantly, the device is connected to the web and exists within a series of other apps on your smartphone that are often capable of delivering content to various social media. Beyond being social, the applications make it far easier to apply different filters to photos than did point-and-shoot cameras or using photo editing software on your computer.

But the question I am asking with this essay is not just about the rise of digitally manipulated social photography, but why these digitally manipulated photos showing up in our social media streams are manipulated specifically to look vintage. Why do so many of us prefer to take, share and view these faux-aged photos?

Is Picture-Quality the Reason?

Perhaps, as another blogger noted, it is the low quality of phone cameras that has lead to the rise of faux-vintage. Maybe the current quality of smartphone cameras tends to produce stale photographs which are then made more interesting when given a faux-vintage filter? Photographers have long known that, depending on the situation, a gritty photo can be as good as or better than a technically perfect shot, and now everyone with a smartphone can take an interesting picture with just one additional press of a button. But, this explanation does little to explain why we equate vintage with interesting in the first place. [Also, many current smartphone cameras are of high quality].

Poets and Scribes?

Another reason for the rise of faux-vintage photography might be that these apps allow us to be more creative with our photos. Susan Sontag in the wonderful On Photography discusses how photography is always both the capturing of truth as well as a subjective creation. In this sense, when taking a photograph we are at once both poets and scribes; a point that I have used to describe our self-documentation on social media: we are both telling the truth about our lives as scribes, but always doing so creatively like poets. So, if “photography is not only about remembering, it is [also] about creating,” then the rise of smartphones and photo apps have democratized the tools to create photos that emphasize art, not just truth. But, again, this explanation would only explain why we might want to manipulate photos in the first place. It does not explain why so many of us have so often chosen to manipulate them into looking specifically retro/vintage.

In the next post, I will argue that the rise of faux-vintage photos using apps like Hipstamatic and Instagram is part of a grasp for authenticity. The photos evoke “a nostalgia for the present” that grants them a feeling of being more authentic and real. The third and last part of this essay will describe how the faux-vintage photo is indicative of a larger trend surrounding how our lives are increasingly always a potential document, and I will conclude the essay with a prediction about the future of the faux-vintage photo.

look out for part II tomorrow and part III thursday

The Facebook “like” button is only one year old, but has already become ubiquitous across the web, and the globe [via Facebook]. Theorizing the effect of this is becoming an important new project.

The Facebook “like” button is only one year old, but has already become ubiquitous across the web, and the globe [via Facebook]. Theorizing the effect of this is becoming an important new project.

Zizek writes this week in Inside Higher Ed about how cloud computing is a space dominated by two or three companies (read: Apple and Google). He states,

Zizek writes this week in Inside Higher Ed about how cloud computing is a space dominated by two or three companies (read: Apple and Google). He states,

“cloud computing offers individual users an unprecedented wealth of choice — but is this freedom of choice not sustained by the initial choice of a provider, in respect to which we have less and less freedom? Partisans of openness like to criticize China for its attempt to control internet access — but are we not all becoming involved in something comparable, insofar as our “cloud” functions in a way not dissimilar to the Chinese state?”

Is a computing market dominated by a few private companies really similar to the “Great Firewall” (officially, the “Golden Shield”) of China?