Larry Sanger, the co-founder of Wikipedia, wrote a wonderful piece on the rise of a new geek anti-intellectualism. The essay sparked much discussion and Sanger has done a terrific job responding to comments and even offering a thoughtful follow-up piece. However, I would like to write a short critique on a couple of points that have yet to be addressed.

Larry Sanger, the co-founder of Wikipedia, wrote a wonderful piece on the rise of a new geek anti-intellectualism. The essay sparked much discussion and Sanger has done a terrific job responding to comments and even offering a thoughtful follow-up piece. However, I would like to write a short critique on a couple of points that have yet to be addressed.

First, I have to mention that contemporary anti-intellectualism was really my first academic interest, spurred in 2000 when I heard that Al Gore lost debates to George W. Bush because Gore “sounded too smart.” Hyper-focused on epistemology (the philosophy of knowledge) at the time, it was learning about the differences between Wikipedia co-founders Larry Sanger and Jimmy Wales that first got me interested in technology as a topic of research. Sanger, himself having an epistemology background, wanted Wikipedia to have a component of expertism on the site. When that was rejected he left and started the Citizendium project. At war are two epistemologies: one based in populism and the other expertism (though, this conceptualization is far too simplistic, it will have to do for this short post).

Today, I focus on theorizing technology and was, of course, quite interested when Larry Sanger took on the rise of a new geek anti-intellectualism, stating that,

more and more mavens of the Internet are coming out firmly against academic knowledge in all its forms.

Sanger lays out what he means by “geek anti-intellectualism” in 5 bullet points:

1. Experts do not deserve any special role in declaring what is known. Knowledge is now democratically determined, as it should be. (Cf. this essay of mine.)

2. Books are an outmoded medium because they involve a single person speaking from authority. In the future, information will be developed and propagated collaboratively, something like what we already do with the combination of Twitter, Facebook, blogs, Wikipedia, and various other websites.

3. The classics, being books, are also outmoded. They are outmoded because they are often long and hard to read, so those of us raised around the distractions of technology can’t be bothered to follow them; and besides, they concern foreign worlds, dominated by dead white guys with totally antiquated ideas and attitudes. In short, they are boring and irrelevant.

4. The digitization of information means that we don’t have to memorize nearly as much. We can upload our memories to our devices and to Internet communities. We can answer most general questions with a quick search.

5. The paragon of success is a popular website or well-used software, and for that, you just have to be a bright, creative geek. You don’t have to go to college, which is overpriced and so reserved to the elite anyway.

While I largely agree with this analysis, I think it can also be improved a bit conceptually in two important ways.

I. Geeks May Be Anti-Expert, But Are They Anti-Reason and Unreflectively Instrumental?

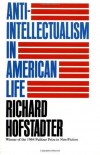

While Sanger cites Richard Hofstadter’s Pulitzer-Prize-winning 1963 book, Anti-Intellectualism in American Life, I think there is much contained in this book that is left untapped by Sanger, and his analysis suffers a bit. Some time should be spent analyzing the concept anti-intellectualism to get a proper definition. Following Hofstader (and Daniel Rigney*), we might say that anti-intellectualism consists of (at least) three dimensions: (1) anti-expertism, the rejection of specialized knowledge and the populist embracing of common-sense and the crowd; (2) anti-reason, which was religious evangelicalism for Hofstadter, and anti-rationalism for Rigney, however, I think it is better labeled anti-reason because it deals with all accounts where knowledge is not situated by reason but instead by some other dogma (which is, usually, but not exclusively, religious); and (3) unreflective instrumentalism, the notion that ideas and knowledge must be put to work rather than being appreciated for their own sake (the so-called “life of the mind”).

While Sanger cites Richard Hofstadter’s Pulitzer-Prize-winning 1963 book, Anti-Intellectualism in American Life, I think there is much contained in this book that is left untapped by Sanger, and his analysis suffers a bit. Some time should be spent analyzing the concept anti-intellectualism to get a proper definition. Following Hofstader (and Daniel Rigney*), we might say that anti-intellectualism consists of (at least) three dimensions: (1) anti-expertism, the rejection of specialized knowledge and the populist embracing of common-sense and the crowd; (2) anti-reason, which was religious evangelicalism for Hofstadter, and anti-rationalism for Rigney, however, I think it is better labeled anti-reason because it deals with all accounts where knowledge is not situated by reason but instead by some other dogma (which is, usually, but not exclusively, religious); and (3) unreflective instrumentalism, the notion that ideas and knowledge must be put to work rather than being appreciated for their own sake (the so-called “life of the mind”).

Sanger’s dimensions of geek anti-intellectualism can be similarly systematized. Sanger’s points 1 and 2 above both describe anti-expertism. They deal with a populist democratization of both the production and consumption of knowledge (i.e., “prosumption”). This is the populist epistemology where the crowd both produces content that is, then, collaboratively decided to be true or not.

Sanger’s point 3 reveals three additional aspects of geek anti-intellectualism: that material is more likely to enter our knowledge base if it is short, exciting, and easy to digest. I think these also point to the populism surrounding the “anti-expertism” dimension in that these attributes all describe how to make content appeal to many people (populism). Sanger’s point 5 deals with popularity, which most directly points to the populist notion of anti-expertism. (I’ll deal with his point 4 in a moment).

Thus, Sanger has done much to demonstrate that there is indeed a geek anti-intellectualism because it centers on a populist rejection of expertism. I think looking more closely at Hofstadter better organizes Sanger’s points. However, more work should be done to see if geeks display the other dimensions of anti-intellectualism: are they evangelical/dogmatic in their knowledge justification (beyond populism)? Do they appreciate knowledge and thinking for its own sake, or does it always have to be put to work towards instrumental purposes? Neither of these points are substantiated by Sanger (yet).

I would argue that geeks are not dogmatic, but instead typically rely on reason (e.g., they employ reason in their defense of populism and the “wisdom of the crowds”; even if I and many others are unconvinced). Further, geeks indeed do seem to engage in knowledge projects for fun. Part of the success of Wikipedia is that it allows for purposelessly clicking through random entries for no other reason than because learning is fun. However, my task in this essay is to better conceptualize Sanger’s points and not really make the case for a geek intellectualism. I’m only half-convinced myself of these last two points. I’ll leave it to Sanger to describe how geeks are anti-intellectual on these other two dimensions of anti-intellectualism. Until then, the story of geek anti-intellectualism remains mixed.

II. Intelligence Versus Intellect

Let’s muddle things further by bringing up perhaps the main reason Sanger should take another look at Hofstadter’s famous book, and it deals with Sanger’s 4th bullet point above (the decline of memorization online). Sanger has conflated intellect and intelligence in his essay. He repeatedly accuses geek culture as being anti-knowledge, which indeed follows from his analysis. However, Sanger’s title refers to anti-intellectualism. Hofstadter’s essential distinction between intelligence and intellect (see 1963;24-25) is that the former means having lots of knowledge and facts whereas the latter deals with creative and contemplative thought (the “life of the mind”). A computer has intelligence whereas Hofstadter and Sanger also have intellect.

Let’s muddle things further by bringing up perhaps the main reason Sanger should take another look at Hofstadter’s famous book, and it deals with Sanger’s 4th bullet point above (the decline of memorization online). Sanger has conflated intellect and intelligence in his essay. He repeatedly accuses geek culture as being anti-knowledge, which indeed follows from his analysis. However, Sanger’s title refers to anti-intellectualism. Hofstadter’s essential distinction between intelligence and intellect (see 1963;24-25) is that the former means having lots of knowledge and facts whereas the latter deals with creative and contemplative thought (the “life of the mind”). A computer has intelligence whereas Hofstadter and Sanger also have intellect.

The dismissal of memorization online is indeed an attack on knowledge and intelligence but not necessarily a dismissal of intellect. While the geeks argue that focusing less on memorizing facts provides more time for creative and contemplative thought, Sanger’s rebuttal points “only” to a geek anti-knowledge/intelligence stance, but not towards a geek anti-intellectualism. The creative and contemplative piece that differentiates intelligence and intellectualism requires little memorization. Some is necessary, sure, but it certainly is not the essence of the difference.

In sum, I think there is a partial argument to be made that the geeks Sanger describes are anti-intellectual; specifically, in their rejection of experts in favor of the crowd. However, the rest of Sanger’s analysis really points to how these geeks remain intellectual, even if they are anti-intelligence/anti-knowledge. What is missing in is evidence that these geeks reject the life of the mind.

To conclude, I am left partially agreeing with Sanger after re-conceptualizing his analysis: (1) the “geeks” are partly anti-intellectual (their populism); (2) they are perhaps partly intellectual (their seeming appreciation, at times, of the life of the mind; though I bet Sanger can convince me out of this); and (3) the geeks are often anti-knowledge (Sanger’s convincing argument surrounding their attack on memorization). And this final point, that the geeks have been shown to be anti-intelligence, is indeed an important contribution (even if mis-labeled by Sanger as anti-intellectualism).

*Rigney, Daniel. 1991. “Three Kinds of Anti-Intellectualism: Rethinking Hofstadter.” Sociological Inquiry. 61(4):434-451.

Following Bataille, philosopher

Following Bataille, philosopher  All this is true, but even if we are as honest online as off, we should not forget that offline self-presentation is a creative performance as well.

All this is true, but even if we are as honest online as off, we should not forget that offline self-presentation is a creative performance as well.

Beyond Global Voices,

Beyond Global Voices,

As the 2012 presidential race ever so slowly gains momentum it remains clear that social media will be influencing elections for a long time to come. In the long run, does the shift towards social media campaigning change who is perceived to be a legitimate candidate? If so, social media might change who wins elections and therefore changes how we are governed. Avoiding [for now] the issue of whether social media has inherent tendencies towards the left or right, what I want to ask is: opposed to old media, does new media benefit political underdogs and outsiders?

As the 2012 presidential race ever so slowly gains momentum it remains clear that social media will be influencing elections for a long time to come. In the long run, does the shift towards social media campaigning change who is perceived to be a legitimate candidate? If so, social media might change who wins elections and therefore changes how we are governed. Avoiding [for now] the issue of whether social media has inherent tendencies towards the left or right, what I want to ask is: opposed to old media, does new media benefit political underdogs and outsiders?