Social media blurs private and public, production and consumption, play and work, physical and digital. There. I just saved myself about 500 words worth of work.

Now with this blurring framework in mind, let us take a look at Facebook’s newest feature: Pay-to-Promote posts.

Back in May, Facebook began allowing brands to pay to promote their pages. This feature gave fan page administrators the opportunity to increase visibility. I say “brands” here, instead of “businesses” because fan pages represent a range of organizations, companies, and even individual “celebrities” (e.g. journalists, academics, actors, musicians etc.). Not much buzz surrounded this new feature, as paid brand promotion is a well established and fairly expected course of action, even within social spaces. Then, on October 3, 2012 Facebook began testing promoted posts for personal pages. My Twitter feed exploded (though ironically, not my Facebook feed, but this is probably due to different networks on each platform).

This feature has actually been around for several months, just not in the U.S. Facebook first released the personal pay-to-promote feature in New Zealand in May, and has since made it available in 20 other countries. The feature allows personal users to pay money (tentatively, the amount looks to be $7) to promote posts (pictures, status updates, party invitations, announcements etc.), locating these updates at the top of their Friends news feeds. The customer then receives feedback on the level of improved visibility that their $7 bought. Reactions seem to sway between anger, discomfort, and dismissal. I want to talk theoretically about why we’re angry and uncomfortable, and speculate about the extent to which we can dismiss this as a doomed financial venture for Facebook.

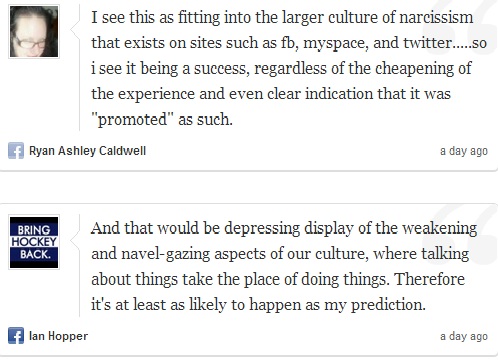

The current Facebook algorithm tailors each person’s news feed based on user interaction and interest. If a user clicks and/or interacts with another page frequently, updates from that page are made more visible. Those with whom the Facebook user does not frequently interact become less visible. In this sense, interaction begets visibility, which begets interaction. I have talked previously about the curation of the social media landscape, where users make choices about who to follow and unfollow, who to Friend and UnFriend, who to highlight, unsubscribe, or hide altogether. We see here a sort of implicit version of this curation, by which user propensities curate the landscape quietly and without curatorial efforts. The pay-to-promote feature messes with this quiet curation, and that makes people angry. For example:

Users want to use Facebook to interact with Friends. The ones they care about. Yet, users are often Friends with more people than those with whom they care to interact. These are connections born of obligation, norms of politeness, or occasional curiosity. They don’t much care about the baby pictures, political rants, or drunken stories from these Friends. Up until now, Facebook has abided by this general disinterest, de-emphasizing the interactionally ignored without any explicit efforts on the part of the user (although users can and sometimes do hide these posts/Friends altogether). The pay-to-promote feature disrupts the interest-based algorithm, and forces potentially unwanted content into a harmoniously accomplished setting, possibly requiring more explicit curatorial work.

This does more than make people annoyed. It also makes people uncomfortable. For example:

- From my own Facebook page in response to a link and a prompt about the pay to promote feature (shared with permission)

This speaks in many ways to the allusive term that Whitney Erin Boesel (@phenatypical) scrambled to come up with last week. Paying to promote a personal status not only makes us aware of identity work and the connection between network benefits and resources, but also, as Nathan Jurgenson (@nathanjurgenson) points out in the comments section of Whitney’s piece discussed above, isolates these connections within the realm of social media, obscuring their presence in the offline realm through juxtaposition.

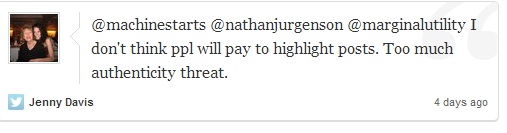

Finally, some (including me) have been dismissive, arguing that this feature will likely not take off. I make the argument quite simply on Twitter:

I want to expand a bit upon this here. I argued that paid posts pose too much of an authenticity threat, deterring use. This was met with a flurry of questions about whether those viewing the post would see that it was “promoted.” The general point behind this question was to argue that if the promotion were invisible, the authenticity threat would be ameliorated. I disagree. Jessica Vitak (@jvitak) finally showed that indeed, the promotional status will be visible. I want to argue that while transparency matters, it is not all that matters. The importance of seeing (versus not seeing) that a post was promoted rests on the notion of others as the judge of authenticity. It rests on the assumption that social actors work to seem authentic. This is not a wrong assumption, but certainly incomplete.

Social actors do not only work to seem authentic, but to be authentic. We try to keep identity work hidden not only from others, but also—perhaps especially—from ourselves. We come to know ourselves through the perceived eyes of others, but also by watching our own behaviors, seeing what we do. To pay to promote a status update—whether or not it is publicly visible—poses a strong threat to authenticity. The user has to see hirself take the action, and moreover, document this action in hir tangible social media reflection.

With this logic, I speculate that individual Facebook users will utilize the feature rarely. When they do, it will likely be as a representative of an organization (e.g. promoting a fundraiser), not an unsimilar usage to the brand promotion already available. This, of course, is an empirical question, and I look forward to seeing how it all plays out.

P.S. Also check out Chris Baraniuk’s (@machinestarts) blog post inspired by the Twitter conversation displayed above

Jenny Davis is a Doctoral Candidate in the Department of Sociology at Texas A&M University. Follow Jenny on Twitter @Jup83.

Comments 3

Doug Hill — October 9, 2012

Smart, excellent analysis! This whole desperate struggle to at least LOOK authentic, if we can't actually BE authentic, as discussed in this and other posts over the past week or so, is just fascinating. Apparently this turning into a cyborg business is not without its strains!

Apps, Autonomy, & Anxiety: a Sociological Perspective » Cyborgology — October 13, 2012

[...] week were Klout and Facebook’s new “sponsored” status updates (which Jenny Davis has since explored in greater depth); this week, I’m going to take a look at ‘helpful’ devices and smartphone [...]

Surrogate Pay-To-Promote: A New Network of Exchange? » Cyborgology — February 18, 2013

[...] October, Facebook began offering a paid promotion option to its users. This gave users the opportunity to pay money for their pictures and status [...]