Several weeks ago, I wrote about the “fear of being missed (FOBM).” The flip side of FOMO (fear of missing out), FOBM captures the anxiety surrounding a complex and fast moving online realm in which it is easy to be buried, ignored, and/or forgotten. This anxiety is amplified by the online/offline connectedness, through which invisibility online can lead to neglect offline (personally and professionally). FOMO and FOBM speak to the difficulty of deleting social media accounts, the discomfort of a dead cell/laptop/tablet battery, and the drive to livetweet, status update, tag oneself in pictures, and be physically present for tagable photo-ops.

Soon after posting my piece on Cyborgology, I read Tiana Bucher’s article in New Media & Society about Facebook algorithms and the fear of invisibility. Bucher’s work offers a useful theoretical frame (Foucault’s Panoptican) for FOBM, and an equally good (if not better) term for the phenomena (fear of invisibility). In what follows, I describe Bucher’s piece and its utilization. I then offer critiques of her work. In this way, I hope to further the theoretical substance of FOBM, framing it with the tools suggested by Bucher, and refining it through juxtaposition to Bucher’s arguments.

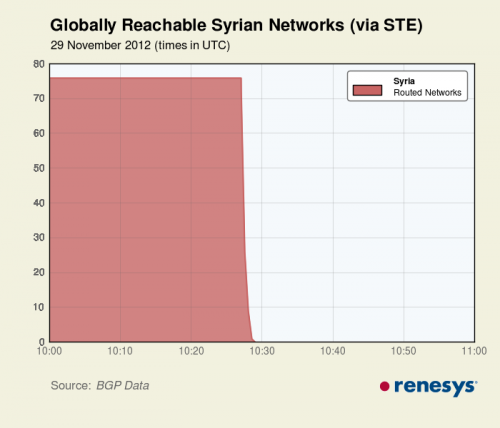

Bucher comes from a Foucauldian perspective, but takes a new angle. Foucault famously describes the disciplinary technology of the panopticon, an architectural form that grants power to the seer over the always potentially seen. Epitomized in prisons, schools and hospitals, the subject must always assume s/he is watched, and must therefore discipline hirself accordingly. Numerous researchers have applied Foucault’s panoptic model to digital surveillance (see examples here, here, and here). The key threat is ubiquitous visibility, an end to privacy, and instilled normative discipline. Bucher flips this panoptic model. She argues that social network sites’ discriminating algorithms produce not a threat of full visibility, but instead, create a dearth of vlisibility. In short, the real threat is that of invisibility. As a case example, Bucher describes how EdgeRank—Facebook’s algorithmic system that shapes News Feed content—works, resulting in about a 12% chance for one’s post to end up in their network’s Top News. There are 3 main components of Edgerank:

- Affinity: those with whom a user is more intimately connected have increased News Feed visibility

- Weight: Some interactions are weighted more than others. For instance, a “Like” weighs less than a photograph

- Time Decay: Older objects are less visible. Newer objects are more visible

This algorithm creates a self-perpetuating loop, such that those who are less visible are less frequently objects of interaction, decreasing further their visibility. To remain visible and relevant within one’s network, the subject must manage these algorithmic preferences. S/he must update frequently (time decay), engage intimately (affinity), and participate substantively (weight).

Foucault is indeed a useful frame with which to understand the algorithmic and behavioral dynamics of visibility on social media. Bucher’s angle on Foucault is unique among the literature, and captures an important experiential component of mediated interaction in the contemporary era. As such, Bucher’s use of Foucault is a fruitful frame with which to theorize FOBM (or fear of invisibility as she aptly calls it).

Pushing Bucher’s work (and my own) further, I offer the two main critiques:

First, Bucher’s argument is algorithmically deterministic. Indeed, visibility and privacy are guided by algorithms, but far from determined by them. Most significantly, visibility need not be directly tied to digital communication (e.g. posting and commenting on pictures). Rather, one can increase hir visibility while away from the computer by simply attending events in which others will check in, post pictures, send invitations etc. Moreover, viewers actively surpass the algorithmic preferences through highlighting some Friends and types of content, and hiding, deleting, or minimizing others (for a full discussion of this second point, see my earlier post on reality curation). In this vein, a Facebook user may perform with algorithmic perfection, messaging, updating frequently, and posting lots of substantive content, but if this content is of the “wrong” type (e.g. politically inflammatory material, pictures of one’s children) or in too high an abundance, the user may find hirself manually removed from hir network’s view, or in extreme cases, deleted as a connection, rendering hir performative work—and hir very presence—obsolete.

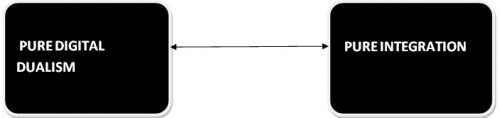

Second, Bucher frames visibility as a juxtaposition between an omnipresent gaze and a laser sharp eye with discriminating vision. For instance, Bucher states:

“…visibility is not something ubiquitous, but rather something scarce.”

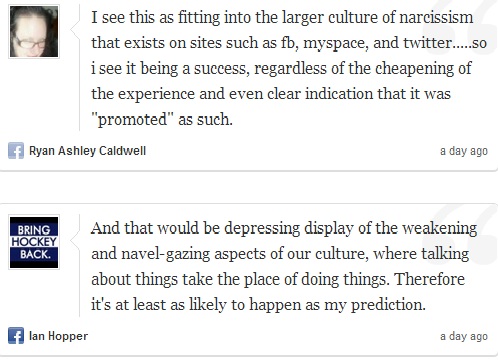

I argue that these poles do not exist in opposition, but in conjunction with one another. Hyper-visibility and invisibility are not mutually exclusive, and the tension between scarcity and abundance becomes part of users’ ambivalent experience with social media. As I have shown elsewhere, the potentialities of a connected era, coupled with competing desires, moral values, and goals of social actors, create a highly ambivalent relationship between humans and the technologies of the time. In the case of visibility, users simultaneously angst over an omnipresent gaze and relegation to the margins (or out of frame altogether). They worry about narcissism, surveillance, and invasions of privacy, while finding pleasure in sharing and micro-stardom.

I think there is a lot more theorizing to be done with regards to visibility. What I hope to have shown here is its complexity. Admittedly, the above post may do more complicating than clarifying.

Pic creds:

Anxiety girl: http://on-account-of.com/

Unfriend: http://blog.hudsonhorizons.com

Jenny Davis (@Jup83) is a weekly contributor for Cyborgology. She wants this post to be visible, so please tweet it, respond to it, and share it on Facebook in an algorithmically effective way (hopefully no one will hide or Unfriend you for it).