Last week Sarah Wanenchak (@dynamicsymmetry) and Whitney Erin Boesel (@phenatypical) separately broached the tensions between technologies, bodies, ownership, and power. Here, I want to articulate this tension more explicitly, and argue that at a broad level, this is a tension between empowerment and dependence. Empowerment—as producers become consumers, reducing institutional authority over identity meanings and cultural representations; dependence— as these identity and cultural prosumers necessarily rely upon increasingly complex technical systems of implementation.

Let us look specifically at the body, as this is the most sharply felt site of contestation. New technologies empower us to take control of our bodies and of ourselves. We can track bodily movement and internal states; we can search the web for alternative opinions and peer-produced information; we can come together with a community of others to prosume embodied experience into individually held and culturally available identity categories. This increased empowerment is indeed technologically facilitated, and indeed liberating. And yet, with each move towards increased empowerment, we embed ourselves more deeply in the biomedical institution, broadening its umbrella of control. We may have the power to define our embodied experiences, but we do so with an institutional language, and within a medicalized logic. We insist on recognition, a label, an infrastructure, and treatment protocols—none of which those without medical authority have the skills to accomplish. All of which makes these non-authoritied subjects dependent upon those who do.

As such, even as medical professionals lose authority over knowledge, they maintain—through a relationship of dependence—authority over subjects’ bodies. This tension is well illustrated through a discussion of contested illness and the internet. Contested illnesses are themselves a product of a biomedical era. In a time of biomedical logics, we expect illnesses to have visible and measurable effects. When embodied experiences—specifically those that cause suffering— are not connected with an observable physiological abnormality, the experience is largely negated. Examples include Fibromyalgia, Multiple Chemical Sensitivity, Restless Leg Syndrome, and a topic I actively research—Transability.

The internet enables those with contested illnesses to come together, establish shared experience, act collectively, exchange advice, coach one another in advocacy, empower themselves through self-identification, educate medical professionals, and lobby for institutional recognition. This institutional recognition is crucial. It is a means by which those with a contested illness receive insurance coverage, the way funding gets channeled into pain management, and the way doctors receive training for, and education about, treatment of the currently unrecognized embodied experience of sufferers.

Because I know the example well, we will take the example of body integrity identity disorder (BIID)—otherwise known as transability. Persons with BIID (PWBs) experience a deep schism between a physically-able body and a self-view of very specific impaired embodiment (e.g. amputation 2 inches above the knee, L3 paraplegia). This embodied experience is currently unrecognized by medical professionals, though it may be included in the upcoming DSM-V. This lack of recognition means that PWBs often find themselves educating therapists, who sometimes reject the transabled client and almost ubiquitously lack the training to treat them properly. It means that transabled persons can be fired from their jobs without protections from the Americans with Disabilities Act. It means that those seeking ability reassignment surgery have no safe,legal, options, let alone insurance coverage. The fight for recognition is therefore a very real fight for resources.

This fight for resources and recognition, however, also locates subjects necessarily in a dependent relationship with medical authorities. Suffering subjects fight to define their bodies in a way that facilitates the surrendering of these bodies to the medical institution. Here, they will be treated with sophisticated technologies operated by those with highly specialized expertise—all of which is far beyond the typical subject’s understanding.

In short, those with contested illnesses take control over definitions of the body while actively relinquishing control over treatment of the body. Next week, I will discuss why, social-psychologically, many suffering subjects view this trade as “worth it.”

Jenny Davis is a Doctoral Candidate in the Department of Sociology at Texas A&M University. Follow Jenny on Twitter @Jup83

Pic credits:

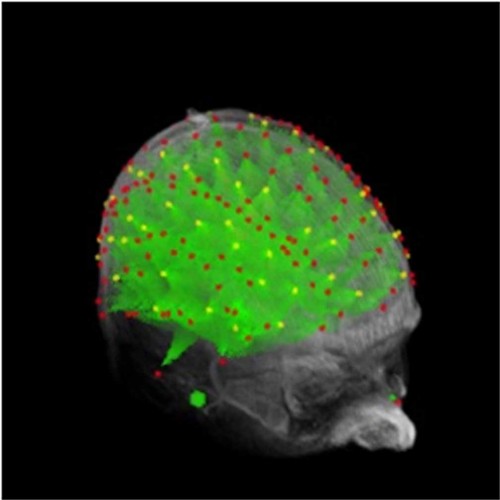

http://www.imaging.beckman.illinois.edu/areas/biomedical.html

Comments 3

Empowerment without Independence | Flash Politics & Society News | Scoop.it — September 11, 2012

[...] Last week Sarah Wanenchak (@dynamicsymmetry) and Whitney Erin Boesel (@phenatypical) separately broached the tensions between technologies, bodies, ownership, and power. [...]

Empowerment without Independence Part II » Cyborgology — September 25, 2012

[...] weeks ago, I talked about the tension between empowerment and dependence in light of pervasive technological advancement in general, and its application to the body in [...]

Empowerment without Independence » Cyborgology | The Sociology of the Quantified Self | Scoop.it — September 29, 2012

[...] [...]