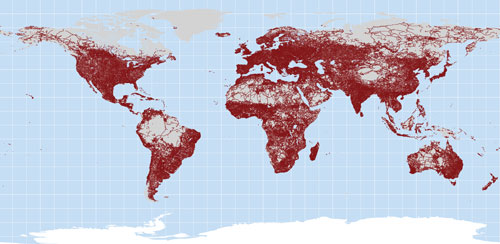

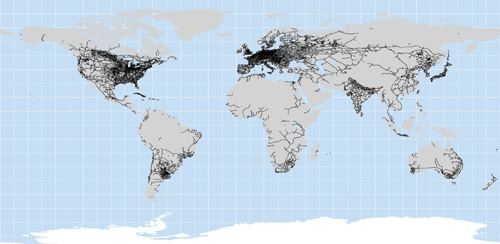

How much of the earth can humans now access? Some images developed by the New Scientist (via ChartPorn) give us some great visuals showing just how thoroughly we’ve colonized the (non-ocean) planet.

A map of all roads:

A map of all railroads:

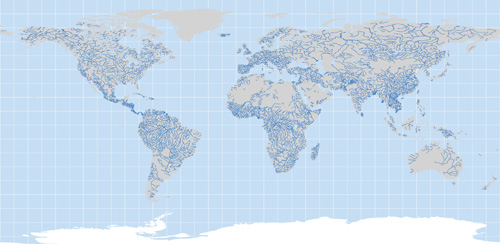

A map of all navigable rivers:

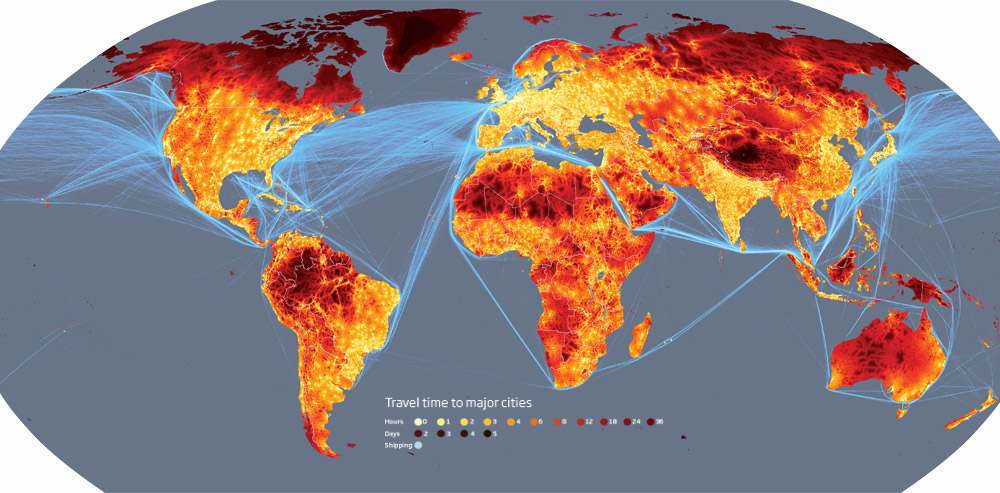

Considering all of these modes of transportation and the type of terrain, the New Scientist calculated how long it would take, from everywhere on the planet, to get to a city of 50,000 people or more:

They estimate that less than 10% of the world is more than two days from the nearest city. The most remote place, they calculate, is the Tibetan plateau.

—————————

Lisa Wade is a professor of sociology at Occidental College. You can follow her on Twitter and Facebook.