Originally posted at Scatterplot.

There has been a lot of great discussion, research, and reporting on the promise and pitfalls of algorithmic decisionmaking in the past few years. As Cathy O’Neil nicely shows in her Weapons of Math Destruction (and associated columns), algorithmic decisionmaking has become increasingly important in domains as diverse as credit, insurance, education, and criminal justice. The algorithms O’Neil studies are characterized by their opacity, their scale, and their capacity to damage.

Much of the public debate has focused on a class of algorithms employed in criminal justice, especially in sentencing and parole decisions. As scholars like Bernard Harcourt and Jonathan Simon have noted, criminal justice has been a testing ground for algorithmic decisionmaking since the early 20th century. But most of these early efforts had limited reach (low scale), and they were often published in scholarly venues (low opacity). Modern algorithms are proprietary, and are increasingly employed to decide the sentences or parole decisions for entire states.

“Code of Silence,” Rebecca Wexler’s new piece in Washington Monthly, explores one such influential algorithm: COMPAS (also the study of an extensive, if contested, ProPublica report). Like O’Neil, Wexler focuses on the problem of opacity. The COMPAS algorithm is owned by a for-profit company, Northpointe, and the details of the algorithm are protected by trade secret law. The problems here are both obvious and massive, as Wexler documents.

Beyond the issue of secrecy, though, one issue struck me in reading Wexler’s account. One of the main justifications for a tool like COMPAS is that it reduces subjectivity in decisionmaking. The problems here are real: we know that decisionmakers at every point in the criminal justice system treat white and black individuals differently, from who gets stopped and frisked to who receives the death penalty. Complex, secretive algorithms like COMPAS are supposed to help solve this problem by turning the process of making consequential decisions into a mechanically objective one – no subjectivity, no bias.

But as Wexler’s reporting shows, some of the variables that COMPAS considers (and apparently considers quite strongly) are just as subjective as the process it was designed to replace. Questions like:

Based on the screener’s observations, is this person a suspected or admitted gang member?

In your neighborhood, have some of your friends or family been crime victims?

How often do you have barely enough money to get by?

Wexler reports on the case of Glenn Rodríguez, a model inmate who was denied parole on the basis of his puzzlingly high COMPAS score:

Glenn Rodríguez had managed to work around this problem and show not only the presence of the error, but also its significance. He had been in prison so long, he later explained to me, that he knew inmates with similar backgrounds who were willing to let him see their COMPAS results. “This one guy, everything was the same except question 19,” he said. “I thought, this one answer is changing everything for me.” Then another inmate with a “yes” for that question was reassessed, and the single input switched to “no.” His final score dropped on a ten-point scale from 8 to 1. This was no red herring.

So what is question 19? The New York State version of COMPAS uses two separate inputs to evaluate prison misconduct. One is the inmate’s official disciplinary record. The other is question 19, which asks the evaluator, “Does this person appear to have notable disciplinary issues?”

Advocates of predictive models for criminal justice use often argue that computer systems can be more objective and transparent than human decisionmakers. But New York’s use of COMPAS for parole decisions shows that the opposite is also possible. An inmate’s disciplinary record can reflect past biases in the prison’s procedures, as when guards single out certain inmates or racial groups for harsh treatment. And question 19 explicitly asks for an evaluator’s opinion. The system can actually end up compounding and obscuring subjectivity.

This story was all too familiar to me from Emily Bosk’s work on similar decisionmaking systems in the child welfare system where case workers must answer similarly subjective questions about parental behaviors and problems in order to produce a seemingly objective score used to make decisions about removing children from home in cases of abuse and neglect. A statistical scoring system that takes subjective inputs (and it’s hard to imagine one that doesn’t) can’t produce a perfectly objective decision. To put it differently: this sort of algorithmic decisionmaking replaces your biases with someone else’s biases.

Dan Hirschman is a professor of sociology at Brown University. He writes for scatterplot and is an editor of the ASA blog Work in Progress. You can follow him on Twitter.

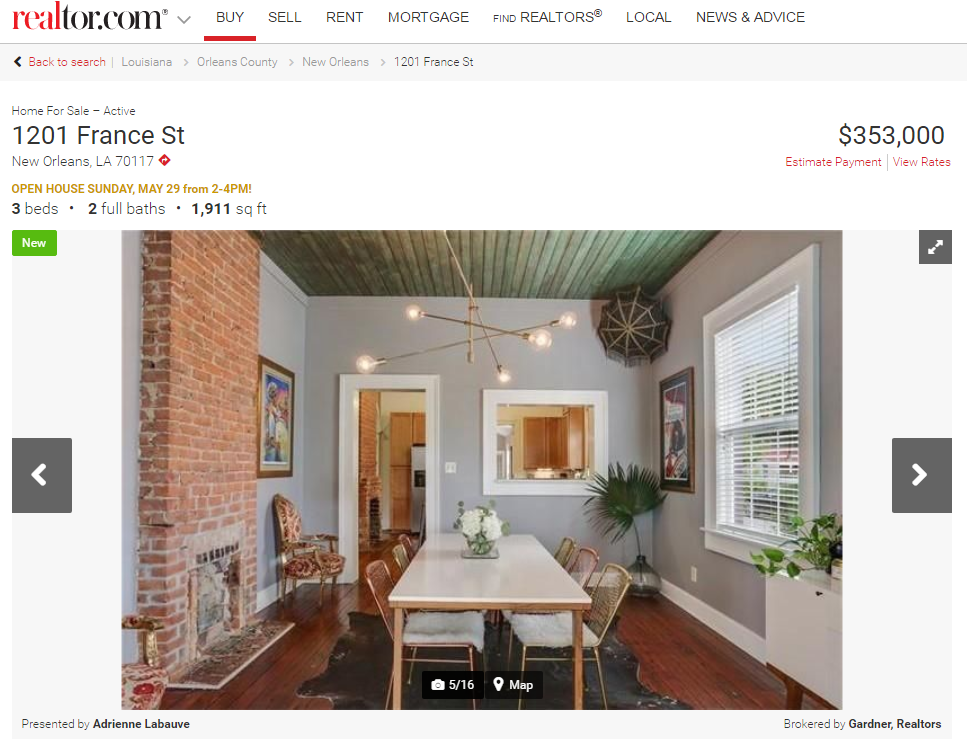

The dining rooms are coming. It’s how I know my neighborhood is becoming aspirationally middle class.

The dining rooms are coming. It’s how I know my neighborhood is becoming aspirationally middle class.

To make a long, well-put, and worth-reading argument short: eviction isn’t rare as many policymakers and sociologists might assume; it is actually a horrifyingly common phenomenon. Urban sociologists have missed the magnitude of the eviction phenomenon because they have traditionally used neighborhoods as the unit of analysis, studying issues such as segregation and gentrification. Because eviction is rarely studied, we don’t have good data on eviction. Establishing a dataset of eviction is not a simple data collecting task, given that there are many forms of informal eviction. The consequences of eviction are devastating and have a profound, negative, and life-long impact on subsequent trajectories: worse housing, more eviction, and homelessness, all disproportionately affecting women of color with children (“a female equivalent of mass incarceration,” Desmond argued at a

To make a long, well-put, and worth-reading argument short: eviction isn’t rare as many policymakers and sociologists might assume; it is actually a horrifyingly common phenomenon. Urban sociologists have missed the magnitude of the eviction phenomenon because they have traditionally used neighborhoods as the unit of analysis, studying issues such as segregation and gentrification. Because eviction is rarely studied, we don’t have good data on eviction. Establishing a dataset of eviction is not a simple data collecting task, given that there are many forms of informal eviction. The consequences of eviction are devastating and have a profound, negative, and life-long impact on subsequent trajectories: worse housing, more eviction, and homelessness, all disproportionately affecting women of color with children (“a female equivalent of mass incarceration,” Desmond argued at a