At the New York Times, Ross Douthat has called out liberals who think, and declare, that churches today are more focused on “culture war” issues like abortion and homosexuality than on poverty.

Ridiculous, says Douthat. Religious organizations spend only “a few hundred million dollars” on pro-life causes and “traditional marriage” but tens of billions on charities, schools, and hospitals. Douthat and his sources, though, lump all spending together rather than separating domestic U.S. budgets from those going to the developing world. But even in the U.S. and other wealthy countries, abortion and gay marriage are largely legislative and legal matters. Building schools and hospitals and then keeping them running – that takes real money.

Why then do liberals get this impression about the priorities of religious organizations? Douthat blames the media. He doesn’t do a full O’Reilly and accuse the media (liberal, it goes without saying) and others of ganging up in a war on religion, but that’s the subtext.

Anyone who tells you that America’s pastors are obsessed with homosexuality or abortion only hears them through a media filter. You can attend Masses or megachurches for months without having those issues intrude.

Actually, the media do not report on the sermons and homilies of local clergy at all, whether they are urging their flocks to live good lives, become wealthy, help the needy, or oppose gay marriage. Nor is there a data base of these Sunday texts, so we don’t know precisely how much American chuchgoers are hearing about any of these topics. Only a handful of clergy get media coverage, and that coverage focuses on their pronouncements about controversial issues. As Douthat says, liberals are probably reacting to “religious leaders who make opposition to abortion more of a political priority than publicly-funded antipoverty efforts.”

Of his own Catholic church, Douthat adds, “You can bore yourself to tears reading denominational statements and bishops’ documents (true long before Pope Francis) with a similar result.” Maybe he has done this reading, and maybe he does think that his Church does not let “those issues intrude.” Or as he puts it, “The belief that organized religion is organized around culture war is largely a conceit of the irreligious.”

But here, thanks to the centralized and hierarchical structure of the Church, we can get data that might reveal what the Church is worried about. As Douthat implies, the previous pope (Benedict XVI, the former Joseph Ratzinger), was more concerned about culture-war issues than is the current pope.

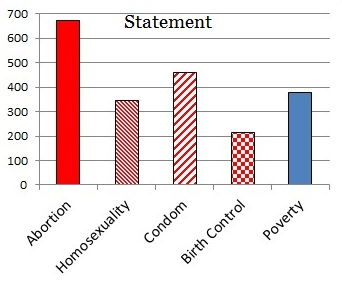

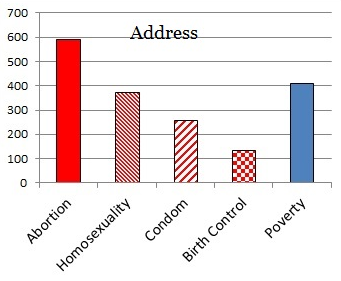

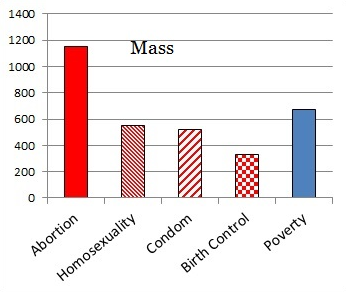

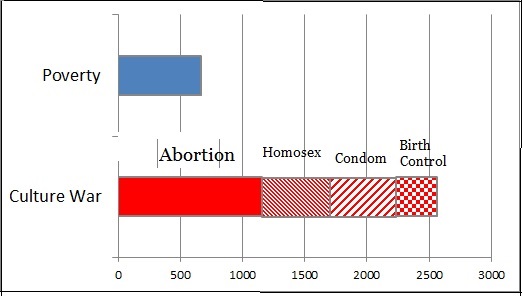

How concerned? I went to Lexis-Nexis. I figured that papal pronouncements on these issues would be issued in masses, in official statements, and in addresses. For each of those three terms, I searched for “Pope Benedict” with four “culture-war” terms (Abortion, Homosexuality, Condom, and Birth control) and Poverty.

Abortion was the big winner. Poverty was referred to in more articles than were the other individual culture-war terms. But if those terms are combined into a single bar, its clear that poverty as a papal concern is dwarfed by the attention to these other issues. The graph below shows the data for “mass.”

This is not the best data. It might reflect the concerns of the press more than those of the Church. Also, some of those Lexis-Nexis articles are not direct hits. They might reference an “address” or “statement” by someone else. But there’s no reason to think that these off-target citations are skewed towards Abortion and away from Poverty.So it’s completely understandable that liberals, and perhaps non-liberals as well, have the impression that Big Religion has a big concern with matters of sex and reproduction.Cross-posted at Montclair SocioBlog and Pacific Standard.

Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.