We’re celebrating the end of the year with our most popular posts from 2013, plus a few of our favorites tossed in. Enjoy!

Last year Lynne Grumet set the internet a-flutter when she appeared on the cover of TIME magazine breastfeeding her toddler. Reactions were largely negative, often reflecting unease at the open display of a sexualized body part being used to feed a child older than the age we generally find acceptable. Others objected to what they saw as the sensationalism of the photo. Grumet later posed on the cover of another magazine in a pose that focused on bonding and intimacy, commonly cited as benefits by breastfeeding advocates. The entire episode tapped into larger cultural anxieties about appropriate mothering.

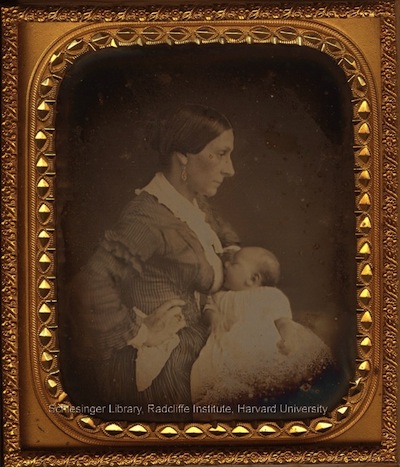

And as Jill Lepore explains in The Mansion of Happiness, it’s just the latest round in the changing discourse about breastfeeding; in the mid-1800s, images of breastfeeding mothers became a fad in the U.S. The use of wet nurses had never been as common in the U.S. as in Europe, and it became even less popular by the early 1800s; breastfeeding your own child became a central measure of your worth as a mother. Cultural constructions of femininity became highly centered on motherhood and the special bond between a mother and her children in the Victorian era.

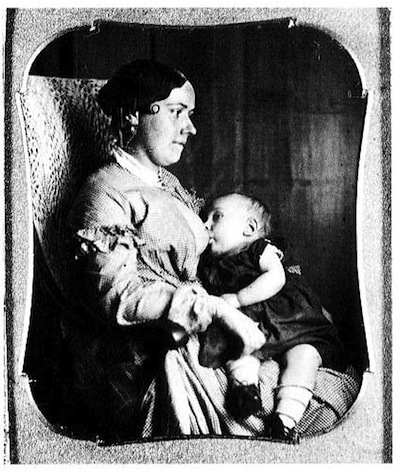

As daguerreotypes became available, women began to pose breastfeeding their infants, capturing them in this most essential of maternal roles:

Cosetra has created a Pinterest board of vintage photos and paintings of breastfeeding that has more examples.

Within decades, American women suddenly seemed to lose the ability to adequately feed their babies, just as infant formula hit the market. Doctors continued to push breastfeeding, but cultural perceptions changed, and with them the social construction of femininity. Rather than being a symbol of maternalism, breastfeeding seemed incompatible with femininity — or, specifically, with white upper-class femininity. Breastfeeding didn’t mesh well with ideas of delicate, refined white women; it was too animal-like, too uncivilized. As Lepore relates, by the early 1900s, a study in Boston found that 9 out of 10 poor mothers breastfed, but only 17% of wealthy mothers did.

By the 1950s, only 20% of mothers nursed their children. Then, ideas about motherhood changed once again; suddenly comparatively privileged, white women were drawn to movements that advocated breastfeeding. Formula came under increased scrutiny. And so continued the ongoing cultural debate over breastfeeding, motherhood, and proper femininity.

Cross-posted at The Huffington Post. Sources: Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University (direct link to daguerreotypes here); Marvelous Kiddo; liveauctioneers.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.