In truth, I didn’t pay a tremendous amount of attention to iOS8 until a post scrolled by on my Tumblr feed, which disturbed me a good deal: The new iteration of Apple’s OS included “Health”, an app that – among many other things – contains a weight tracker and a calorie counter.

And can’t be deleted.

Okay, so why is this a big deal? Pretty much all “health” apps include those features. I have one (third-party). A lot of people have one. They can be very useful. Apple sticking non-removable apps into its OS is annoying, but why would it be something worth getting up in arms over? This is where it becomes a bit difficult to explain, and where you’re likely to encounter two kinds of people (somewhat oversimplified, but go with me here). One group will react with mild bafflement. The other will immediately understand what’s at stake.

The Health app is literally dangerous, specifically to people dealing with/in recovery from eating disorders and related obsessive-compulsive behaviors. Obsessive weight tracking and calorie counting are classic symptoms. These disorders literally kill people. A lot of people. Apple’s Health app is an enabler of this behavior, a temptation to fall back into self-destructive habits. The fact that it can’t be deleted makes it worse by orders of magnitude.

So why can’t people just not use it? Why not just hide it? That’s not how obsessive-compulsive behavior works. One of the nastiest things about OCD symptoms – and one of the most difficult to understand for people who haven’t experienced them – is the fact that a brain with this kind of chemical imbalance can and will make you do things you don’t want to do. That’s what “compulsive” means. Things you know you shouldn’t do, that will hurt you. When it’s at its worst it’s almost impossible to fight, and it’s painful and frightening. I don’t deal with disordered eating, but my messed-up neurochemistry has forced me to do things I desperately didn’t want to do, things that damaged me. The very presence of this app on a device is a very real threat (from post linked above):

Whilst of course the app cannot force you to use it, it cannot be deleted, so will be present within your apps and can be a source of feelings of temptation to record numbers and of guilt and judgement for not using the app.

Apple doesn’t hate people with eating disorders. They probably weren’t thinking about people with eating disorders at all. That’s the problem.

Then this weekend another post caught my attention: The Health app doesn’t include the ability to track menstrual cycles, something that’s actually kind of important for the health of people who menstruate. Again: so? Apple thinks a number of other forms of incredibly specific tracking were important enough to include:

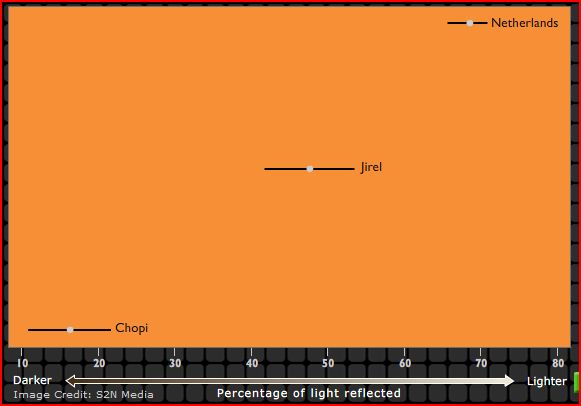

In case you’re wondering whether Health is only concerned with a few basics: Apple has predicted the need to input data about blood oxygen saturation, your daily molybdenum or pathogenic acid intake, cycling distance, number of times fallen and your electrodermal activity, but nothing to do with recording information about your menstrual cycle.

Again: Apple almost certainly doesn’t actively hate cisgender women, or anyone else who menstruates. They didn’t consider including a cycle tracker and then went “PFFT SCREW WOMEN.” They probably weren’t thinking about women at all.

During the design phase of this OS, half the world’s population was probably invisible. The specific needs of this half of the population were folded into an unspecified default. Which doesn’t – generally – menstruate.

I should note that – of course – third-party menstrual cycle tracking apps exist. But people have problems with these (problems I share), and it would have been nice if Apple had provided an escape from them:

There are already many apps designed for tracking periods, although many of my survey respondents mentioned that they’re too gendered (there were many complaints about colour schemes, needless ornamentation and twee language), difficult to use, too focused on conceiving, or not taking into account things that the respondents wanted to track.

Both of these problems are part of a larger design issue, and it’s one we’ve talked about before, more than once. The design of things – pretty much all things – reflects assumptions about what kind of people are going to be using the things, and how those people are going to use them. That means that design isn’t neutral. Design is a picture of inequality, of systems of power and domination both subtle and not. Apple didn’t consider what people with eating disorders might be dealing with; that’s ableism. Apple didn’t consider what menstruating women might need to do with a health app; that’s sexism.

The fact that the app cannot be removed is a further problem. For all intents and purposes, updating to a new OS is almost mandatory for users of Apple devices, at least eventually. Apple already has a kind of control over a device that’s a bit worrying, blurring the line between owner and user and threatening to replace one with the other. The Health app is a glimpse of a kind of well-meaning but ultimately harmful paternalist approach to design: We know what you need, what you want; we know what’s best. We don’t need to give you control over this. We know what we’re doing.

This isn’t just about failure of the imagination. This is about social power. And it’s troubling.

Sarah Wanenchak is a PhD student at the University of Maryland, College Park. Her current research focuses on contentious politics and communications technology in a global context, particularly the role of emotion mediated by technology as a mobilizing force. She blogs at Cyborgology, where this post originally appeared, and you can follow her at @dynamicsymmetry.