Fashion designer Vera Wang is known world-wide for her bridal gowns, costing from thousands of dollars to tens of thousands of dollars. She opened her first store — in New York City — in 1990. In 2011, her gowns started appearing at the discount David’s Bridal, for as little as $600. Today she has a line at Kohl’s.

Why would someone who can sell a $25,000 wedding dress turn around and sell their name to a low-end department store? The answer has to do with money, of course, but it also tells a story about class and distinction. Typically trends start at “the top” with wealthy and high-profile elites. Elites embrace an expensive new look, designer, or product (e.g., men and high heels) in order to distinguish themselves from the rest of the population. The rest then imitate the trend-setters, such that the trend diffuses down throughout the population one class strata at a time. That’s why Wang’s David’s Bridal and Kohl’s collections are called “diffusion lines.”

Vera Wang is hanging in there, but lots of trends die when they diffuse down to the working class. If the working class can take part in the trend, the rich can’t use it to show that they’re special (which is why they sometimes defend their exclusive rights). So it gets dropped. Once the elites move onto something new, the process begins again.

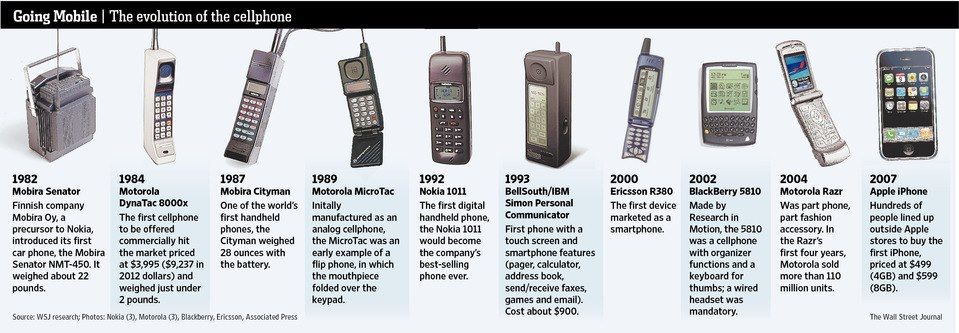

Interestingly, Whitney Erin Boesel, writing for Cyborgology, applies this process to cell phones, or what are better described as “mobile devices.” It applies, of course, to the never-ending stream of newer, faster, shinier devices, but also to the very idea of a cell phone/mobile device. As much as we make fun of the clunky cell phones of the 1980s and ’90s, very few people had them, so having one suggested that you were a Very Important Person. She writes:

When you picture someone using one of those cumbersome early cell phones, whom do you picture? Is it a white guy in a suit, maybe wearing a Rolex and 1980s sunglasses? Yeah, I thought so. When they first came out, cell phones — like pretty much every brand new, expensive technology — were status markers. A cell phone said, “I am wealthy, I am powerful, and I am so important that people must be able to reach me even when I am away from my home or office.”

Today, of course, though certain models do a little to distinguish one user from another, the possession of a mobile device doesn’t signify elite status. As Boesel points out, more people have cell phones than toilets.

Today, of course, though certain models do a little to distinguish one user from another, the possession of a mobile device doesn’t signify elite status. As Boesel points out, more people have cell phones than toilets.

Enter Google glass.

Slate reports that Google co-founder Sergey Brin is arguing that smart phones are “emasculating.” Using masculinity is a metaphor for power, he is appealing to the elite to move on to the next technology. A smart phone, in other words, “no longer signifies [that is a person is] a member of the power elite.” It’s a pretty snappy — and downright Bourdieuian — way of marketing a new technology to the very people who will drive its success.

Brin starts his discussion about this at 4 minutes, 25 seconds:

Cross-posted at Pacific Standard.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.