There was a great article in The Nation last week about social media and ad hoc credit scoring. Can Facebook assign you a score you don’t know about but that determines your life chances?

There was a great article in The Nation last week about social media and ad hoc credit scoring. Can Facebook assign you a score you don’t know about but that determines your life chances?

Traditional credit scores like your FICO or your Beacon score can determine your life chances. By life chances, we generally mean how much mobility you will have. Here, we mean a number created by third party companies often determines you can buy a house/car, how much house/car you can buy, how expensive buying a house/car will be for you. It can mean your parents not qualifying to co-sign a student loan for you to pay for college. These are modern iterations of life chances and credit scores are part of it.

It does not seem like Facebook is issuing a score, or a number, of your creditworthiness per se. Instead they are limiting which financial vehicles and services are offered to you in ads based on assessments of your creditworthiness.

One of the authors of The Nation piece (disclosure: a friend), Astra Taylor, points out how her Facebook ads changed when she started using Facebook to communicate with student protestors from for-profit colleges. I saw the same shift when I did a study of non-traditional students on Facebook.

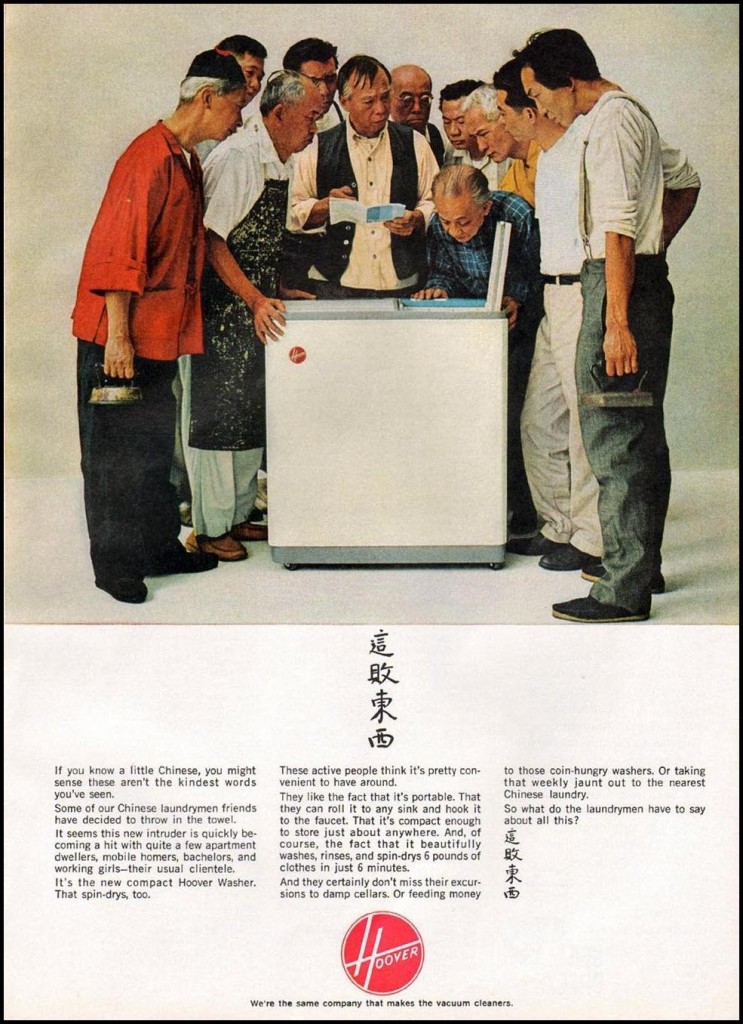

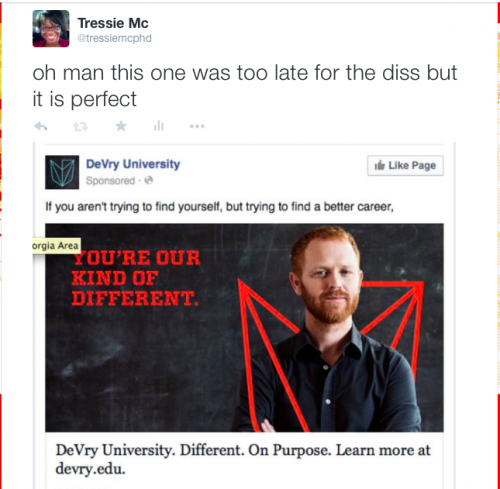

You get ads like this one from DeVry:

Although, I suspect my ads were always a little different based on my peer and family relations. Those relations are majority black. In the U.S. context that means it is likely that my social network has a lower wealth and/or status position as read through the cumulative historical impact of race on things like where we work, what jobs we have, what schools we go to, etc. But even with that, after doing my study, I got every for-profit college and “fix your student loan debt” financing scheme ad known to man.

Whether or not I know these ads are scams is entirely up to my individual cultural capital. Basically, do I know better? And if I do know better, how do I come to know it?

I happen to know better because I have an advanced education, peers with advanced educations and I read broadly. All of those are also a function of wealth and status. I won’t draw out the causal diagram I’ve got brewing in my mind but basically it would say something like, “you need wealth and status to get advantageous services offered you on the social media that overlays our social world and you need proximity wealth and status to know when those services are advantageous or not”.

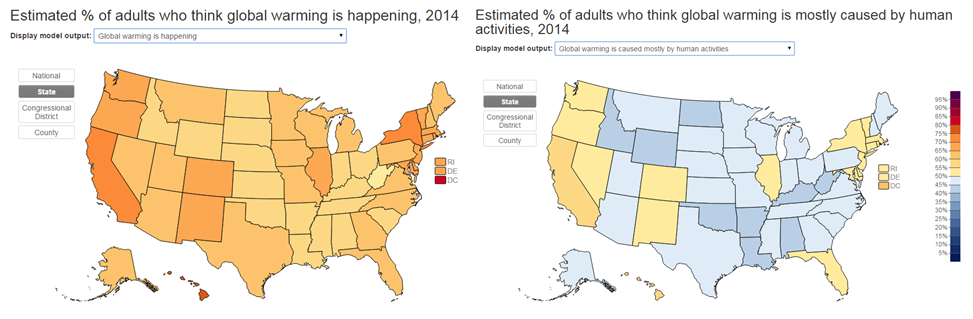

It is in interesting twist on how credit scoring shapes life chances. And it runs right through social media and how a “personalized” platform can never be democratizing when the platform operates in a society defined by inequalities.

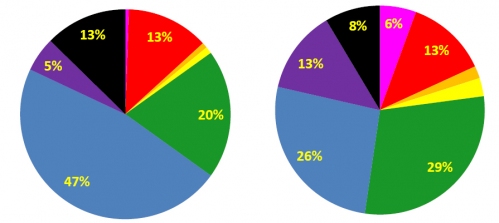

I would think of three articles/papers in conversation if I were to teach this (hint, I probably will). Healy and Fourcade on how credit scoring in a financialized social system shapes life chances is a start:

providers have learned to tailor their products in specific ways in an effort to maximize rents, transforming the sources and forms of inequality in the process.

And then Astra Taylor and Jathan Sadowski’s piece in The Nation as a nice accessible complement to that scholarly article:

Making things even more muddled, the boundary between traditional credit scoring and marketing has blurred. The big credit bureaus have long had sidelines selling marketing lists, but now various companies, including credit bureaus, create and sell “consumer evaluation,” “buying power,” and “marketing” scores, which are ingeniously devised to evade the FCRA (a 2011 presentation by FICO and Equifax’s IXI Services was titled “Enhancing Your Marketing Effectiveness and Decisions With Non-Regulated Data”). The algorithms behind these scores are designed to predict spending and whether prospective customers will be moneymakers or money-losers. Proponents claim that the scores simply facilitate advertising, and that they’re not used to approve individuals for credit offers or any other action that would trigger the FCRA. This leaves those of us who are scored with no rights or recourse.

And then there was Quinn Norton this week on The Message talking about her experiences as one of those marketers Taylor and Sadowski allude to. Norton’s piece summarizes nicely how difficult it is to opt-out of being tracked, measured and sold for profit when we use the Internet:

I could build a dossier on you. You would have a unique identifier, linked to demographically interesting facts about you that I could pull up individually or en masse. Even when you changed your ID or your name, I would still have you, based on traces and behaviors that remained the same — the same computer, the same face, the same writing style, something would give it away and I could relink you. Anonymous data is shockingly easy to de-anonymize. I would still be building a map of you. Correlating with other databases, credit card information (which has been on sale for decades, by the way), public records, voter information, a thousand little databases you never knew you were in, I could create a picture of your life so complete I would know you better than your family does, or perhaps even than you know yourself.

It is the iron cage in binary code. Not only is our social life rationalized in ways even Weber could not have imagined but it is also coded into systems in ways difficult to resist, legislate or exert political power.

Gaye Tuchman and I talk about this full rationalization in a recent paper on rationalized higher education. At our level of analysis, we can see how measurement regimes not only work at the individual level but reshape entire institutions. Of recent changes to higher education (most notably Wisconsin removing tenure from state statute causing alarm about the role of faculty in public higher education) we argue that:

In short, the for-profit college’s organizational innovation lies not in its growth but in its fully rationalized educational structure, the likes of which being touted in some form as efficiency solutions to traditional colleges who have only adopted these rationalized processes piecemeal.

And just like that we were back to the for-profit colleges that prompted Taylor and Sadowski’s article in The Nation.

Efficiencies. Ads. Credit scores. Life chances. States. Institutions. People. Inequality.

And that is how I read. All of these pieces are woven together and its a kind of (sad) fun when we can see how. Contemporary inequalities run through rationalized systems that are being perfected on social media (because its how we social), given form through institutions, and made invisible in the little bites of data we use for critical minutiae that the Internet has made it difficult to do without.

Tressie McMillan Cottom is an assistant professor of sociology at Virginia Commonwealth University. Her doctoral research is a comparative study of the expansion of for-profit colleges. You can follow her on twitter and at her blog, where this post originally appeared.

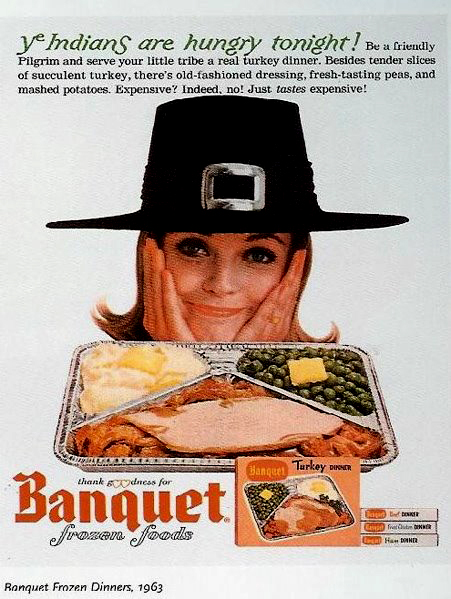

Pre-prepared frozen meals pre-dated the Swanson “TV dinner,” but it was Swanson who brought the aluminum tray — previously only seen in taverns and airplanes — into the home.

Pre-prepared frozen meals pre-dated the Swanson “TV dinner,” but it was Swanson who brought the aluminum tray — previously only seen in taverns and airplanes — into the home.