Societies grow and change all the time, but it can be tough to think about big-picture shifts when you’re living through the practical details of the day to day. Take the recent popularity of large language models (LLMs). In the short term, we face important sociological questions about how they fit into the norms of everyday life. Is it cheating to use an LLM to help you write, or to generate new ideas? How will new kinds of automation change work, or will they take jobs away?

These are important questions, but it is also useful to take a step back and think about what rapid developments in technology might do to our foundational social relationships and core beliefs. I was fascinated by a recent set of studies published in PNAS that suggest automated work and LLMs could even change the way we think about religion.

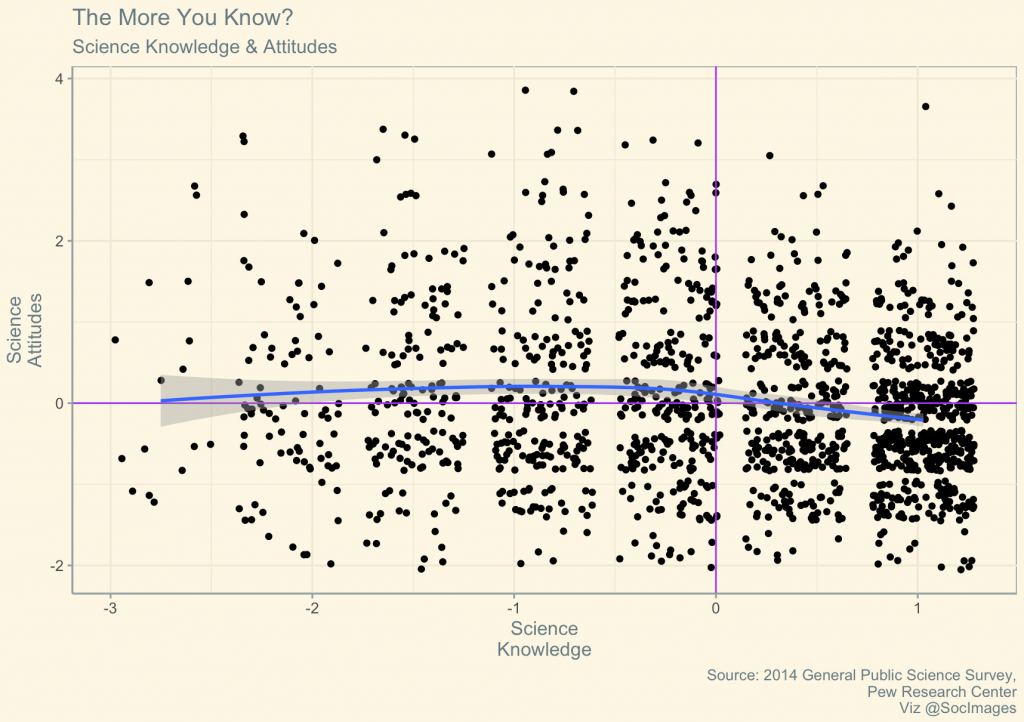

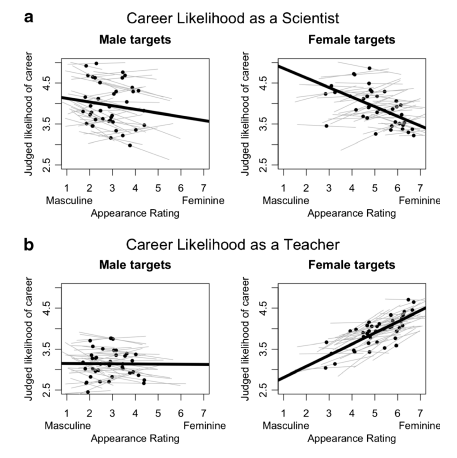

In the article “Exposure to Automation Explains Religious Declines,” authors Joshua Conrad Jackson, Kai Chi Yam, Pok Man Tang, Chris G. Sibley, and Adam Waytz review the findings from five studies. In one, their analysis of longitudinal data across 68 countries from 2006 to 2019 finds nations with higher stocks of industrial robots also tend to have lower proportions of people who say religion is an important part of their daily lives in surveys.

I was most surprised by the results of their fifth study—an experiment teaching people about recent advances in science and AI. Respondents who read about the capabilities of LLMs like ChatGPT showed “greater reductions in religious conviction than learning about scientific advances” (8).

The authors suggest one reason for this pattern is that “people may perceive AI as having capacities that they do not ascribe to traditional sciences and technologies and that are uniquely likely to displace the instrumental roles of religion” (2). This is important for us, whether or not you’re personally religious, because religion is a socially powerful force – people use shared beliefs to accomplish things in the world and solve problems, even to cope with hardships like losing a job.

But these results show that new changes in technology, like the advent of LLMs, might be expanding people’s imaginations about what we can do and achieve, possibly even changing the core beliefs that are central to their lives over the long term.

Evan Stewart is an assistant professor of sociology at University of Massachusetts Boston. You can follow his work at his website, or on BlueSky.