Last Wednesday, January 20 18, over 7000 websites participated in a massive protest opposing bills H.R. 3261, the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) and S. 968, the PROTECT IP Act (PIPA). While these bills aimed to curb online piracy, many fear that they also pave the way for widespread internet censorship. Although consideration of SOPA and PIPA has now been “postponed,” the bills and the protests raise the issue of who has the authority to control access to knowledge. The different visual and technological ways that websites protested SOPA and PIPA demonstrate the importance we as a culture place on unfettered access to information. In imagining what a censored internet might be like, the protests also show how much the medium — in this case, technology — shapes our individual and collective knowledge and what kind of a threat censorship would be. In additional to concerns about free speech and access to information, the protests also remind us how many profitable businesses are based on assumptions that those things will remain uncensored.

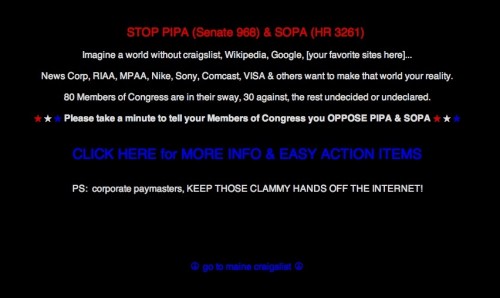

Many sites (such as Craigslist, Pinterest, and icanhascheezburger, screencaps below) took a traditional web protest approach by posting informational messages encouraging visitors to take action against the bills:

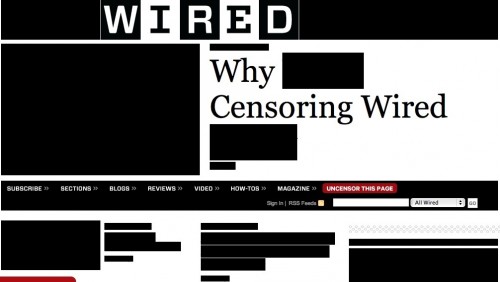

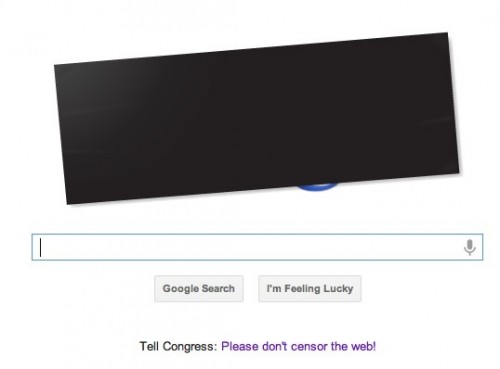

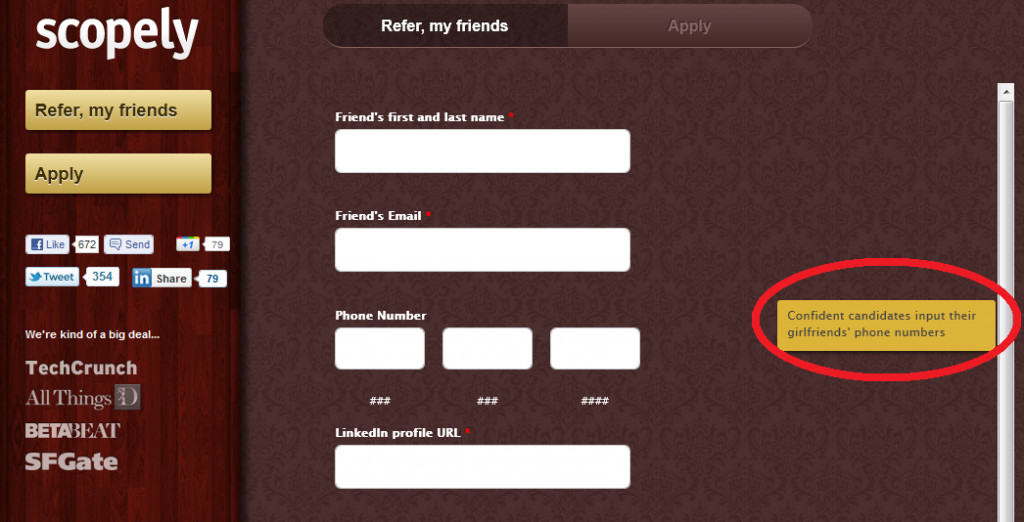

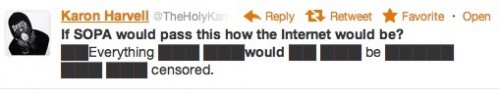

Other websites (WordPress, Wired, Google), along with Facebook status updates and Tweets, visually depicted what internet censorship would look like. This kind of protest is particularly visually powerful — stark black blocks out the text, making the message unreadable:

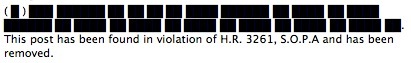

Others shut down altogether (like Wikipedia, Reddit, MoveOn, and Mozilla), essentially removing their website’s resources and information for 24 hours:

Others shut down altogether (like Wikipedia, Reddit, MoveOn, and Mozilla), essentially removing their website’s resources and information for 24 hours:

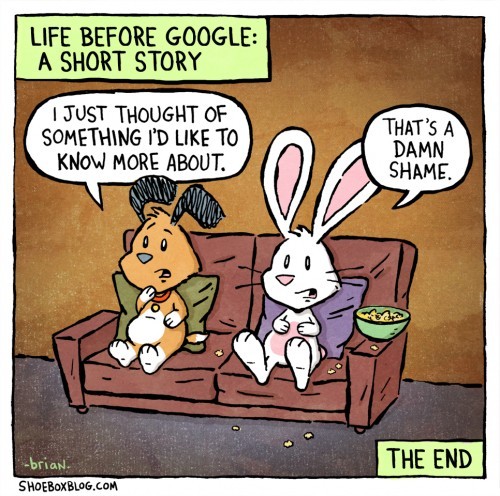

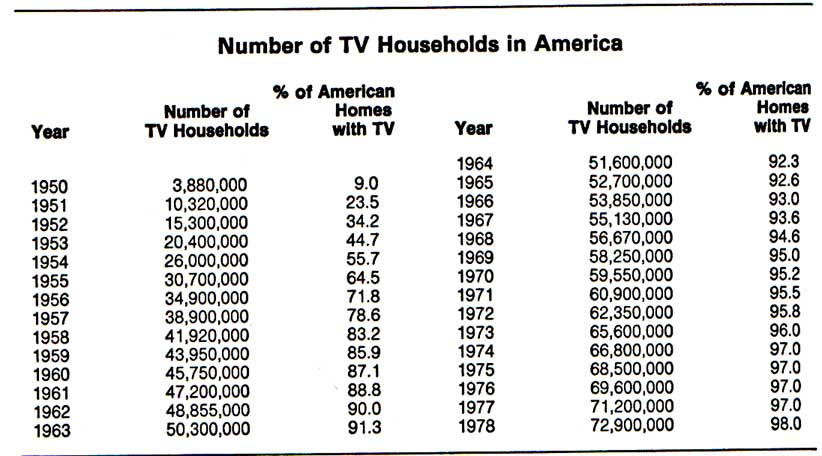

Many of us are fortunate to take for granted open, easy access to information, including open access to everything on the internet (though the continued existence of a digital divide makes such information more available to some than others, and school districts routinely censor online content for students). The protests of SOPA and PIPA illustrate how much we rely on technology for access to information by raising important questions about what censorship would mean for access to knowledge. Seemingly boundless information is at the tips of our fingers everywhere we go:

(Via Shoebox Blog.)

As the cartoon shows, our knowledge is shaped by what medium is physically available to us for seeking new information. Students in my classes can’t fathom a time when they couldn’t look up any bit of information they needed on Google. They can’t imagine the way I used to do research for a school paper– by consulting my family’s dusty encyclopedia set, or heading down to the library. Though their experience is physically removed from the research librarian’s desk, they have access to much more information than I ever did in my local library. The protests against SOPA and PIPA — the website outages and blacked out texts — make real the idea that if the internet were censored, our avenues for learning would shrink.