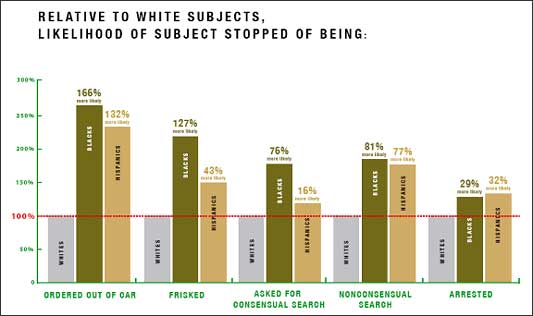

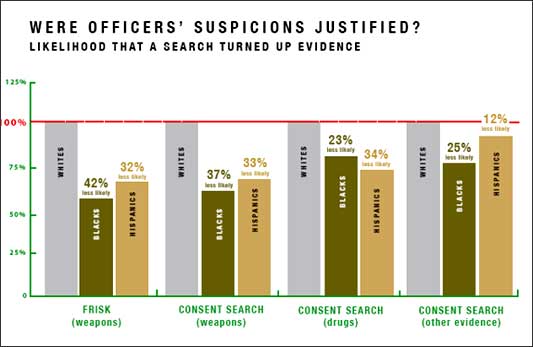

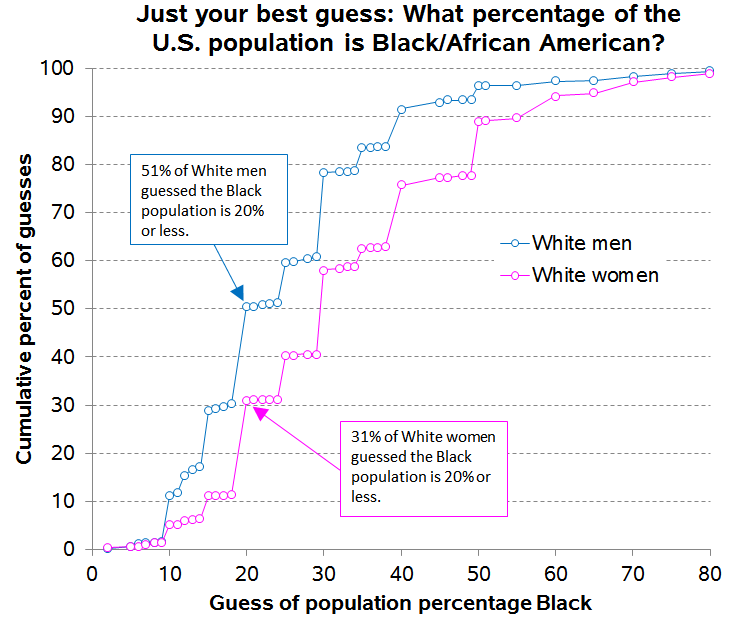

Jay Livingston at Montclair SocioBlog discussed the two figures below (full report here). The first shows that Black and Hispanic drivers are more likely to be stopped by Los Angeles Police than White drivers. The second shows that, when stopped, if searched, police are more likely to find weapons and drugs on Whites than on either Blacks or Hispanics. Conclusion: Blacks and Hispanics are being racially profiled by the L.A.P.D. and racial profiling does not work. Data from New York City in 2008 tells a similar story.

The New York Civil Liberties Union reports that the NYPD stopped 161,000 people in the first quarter of 2011. A record number. Eighty-four percent of those stopped were Black or Latino. The Civil Liberties Union has filed a lawsuit, claiming that the practice is unconstitutional.

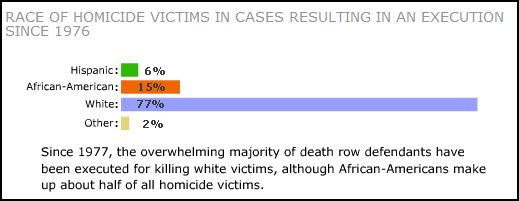

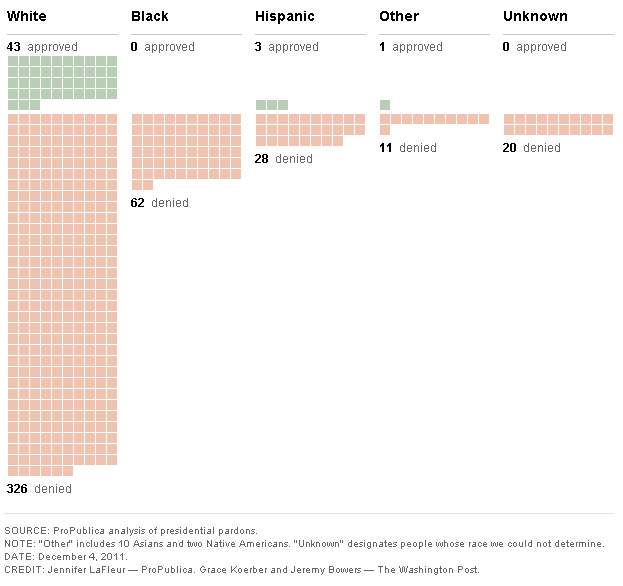

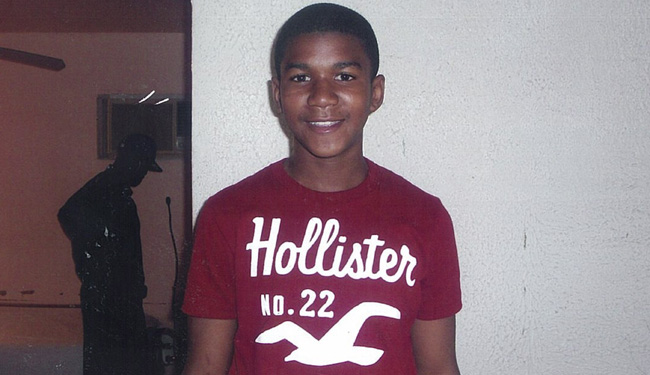

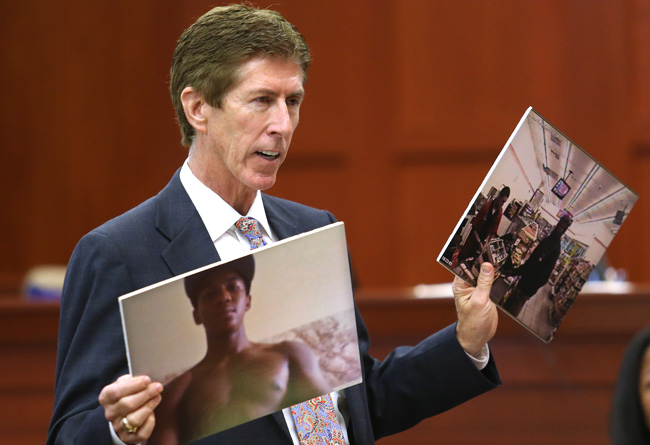

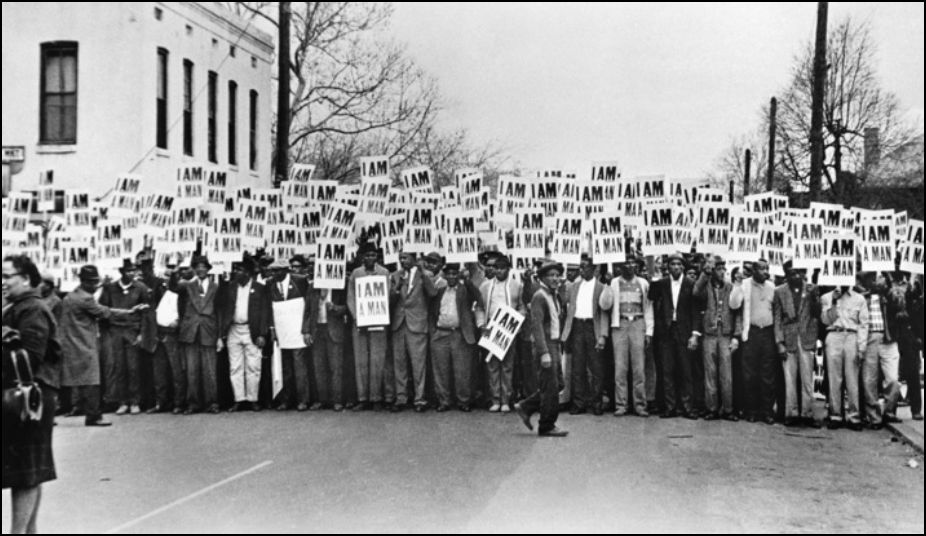

Originally posted in 2011. Re-posted in solidarity with the African American community; regardless of the truth of the Martin/Zimmerman confrontation, it’s hard not to interpret the finding of not-guilty as anything but a continuance of the criminal justice system’s failure to ensure justice for young Black men.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.