Laura Agustin, author of Sex at the Margins: Migration, Labour Markets, and the Rescue Industry, asks us to be critical consumers of stories about sex trafficking, the moving of girls and women across national borders in order to force them into prostitution. Without denying that sex trafficking occurs or suggesting that it is unproblematic, Agustin wants us to avoid completely erasing the possibility of women’s autonomy and self-determination.

About one news story on sex trafficking, she writes:

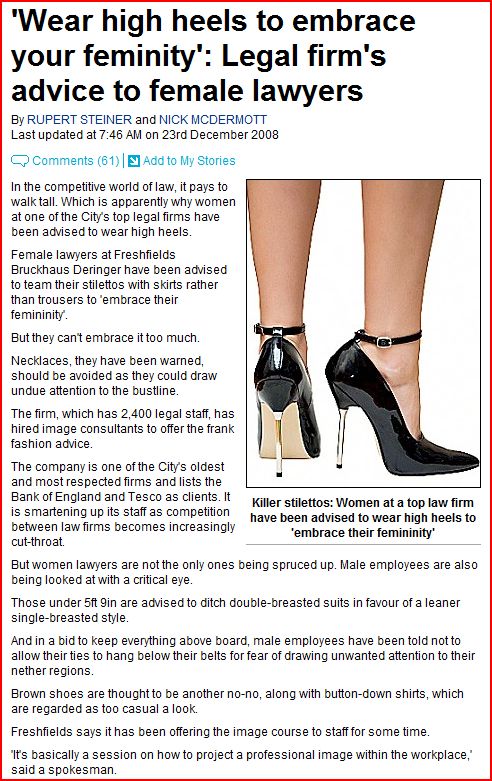

…[the] ‘undercover investigation’, one with live images, fails to prove its point about sex trafficking… reporters filmed men and women in a field, sometimes running, sometimes walking, sometimes talking together.

…I’m willing to believe that we’re looking at prostitution, maybe in an informal outdoor brothel. But what we’re shown cannot be called sex trafficking unless we hear from the women themselves whether they opted into this situation on any level at all. They aren’t in chains and no guns are pointed at them, although they might be coerced, frightened, loaded with debt or wishing they were anywhere else. But we don’t hear from them. I’m not blaming the reporters or police involved for not rushing up to ask them, but the fact is that their voices are absent.

…

There are lots of things we might find out about the fields near San Diego… [but] we don’t see evidence for the sex-trafficking story. Feeling titillated or disgusted ourselves does not prove anything about what we are looking at or about how the people actually involved felt.

Regarding a news clip, Agustin writes:

…a reporter dressed like a tourist strolls past women lined up on Singapore streets, commenting on their many nationalities and that ‘they seem to be doing it willingly’. But since he sees pimps everywhere he asks how we know whether they are victims of trafficking or not? His investigation consists of interviewing a single woman who… articulates clearly how her debt to travel turned out to be too big to pay off without selling sex. Then an embassy official says numbers of trafficked victims have gone up, without explaining what he means by ‘trafficked’ or how the embassy keeps track…

So here again, there could be bad stories, but we are shown no evidence of them. The women themselves, with the exception of one, are left in the background and treated like objects.

To recap, what Agustin is urging us to do is to refrain from excluding the possibility of women’s agency by definition. Why might a woman choose a dangerous, stigmatized, and likely unpleasant job? Well, many women enter prostitution “voluntarily” because of social structural conditions (e.g., they need to feed their children and prostitution is the most economically-rewarding work they can get). Assuming all women are forced by mean people, however, makes the social structural forces invisible. We don’t need mean pimps to force women into prostitution, our own social institutions do a pretty good job of it.

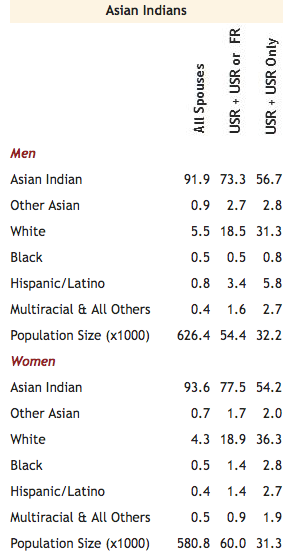

And, of course, we must also acknowledge the possibility that some women choose prostitution because they like the work. You might say, “Okay, fine, there may be some high-end prostitutions who like the work, but who could possibly like having sex with random guys for $20 in dirty bushes?” Well, if we decide that the fact that their job is shitty means that they are “coerced” in some way, we need to also ask about those people that “choose” other potentially shitty jobs like migrant farmwork, being a cashier, filing, working behind the counter at an airline (seriously, that must suck), factory work, and being a maid or janitor. There are lots of shitty jobs in the U.S. and world economy. Agustin simply wants us to give women involved in prostitution the same subject status as women and men doing other work.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.