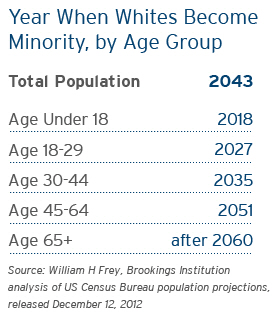

Last week, the news broke that the U.S. Census Bureau is projecting that whites will no longer be the majority by the year 2043. This is at least a year earlier than previous estimates and seven years earlier than the 2050 majority/minority prediction that first got everyone’s attention a few years back.

The Associated Press release that broke the story described the news as a “historic shift” that is “reshaping the nation’s schools, workforce, and electorate.” It attributes the trend to “higher birth rates” among American minorities, especially Hispanics who entered at the height of the immigration boom in the 1990s and early 2000s. (The story also correctly notes that immigration rates from Mexico and elsewhere have slowed dramatically with the housing bust of the previous decade and the economic recession of recent years.) The story claims these demographic shifts are “redefining long-held notions of race” in the U.S.—“easing” residential segregation, increasing intermarriage for some, “blurring” racial and ethnic lines, and “lifting the numbers of people who identify as multiracial.”

All good points, reminding me of the importance of empirical data alongside solid, sociologically informed reporting. Indeed, I had several colleagues tell me that the media coverage made many of the same points that they try to convey in their classes. Still, I couldn’t help but think about all of the other additions and complexities I’d love to see addressed. One is the uncertainty of what these demographic changes imply for American racial hierarchies. There is definitely progress and positivity on some fronts, but this doesn’t apply equally or to everyone. Obviously, one big question is how those who do not fit the historic black-white binary–Hispanics and Asian Americans–will fit in, how they will identify and how they will be identified in the future. I also continue to think about how race and racism is experienced for those at the bottom of the American racial hierarchy and status system–especially those who are poor and dark-skinned.

All of this attention to the growth of the non-white minority populations can mask other key things about race and racial privilege in the U.S. The fact that white Americans may not be the numerical majority for long should not distract us from reality that their power and position at the top of the American racial hierarchy isn’t likely to be challenged anytime soon—at least not within our lifetimes. (For an interesting look at how white Americans construct their own ideas of their race, check out Matt Hughey’s excellent white paper, published last week on TSP).

Numbers don’t lie but they are also more complicated than we often realize, and they certainly don’t speak for themselves. Such is the ongoing challenge of census data and sociology.

Comments 4

Friday Roundup: December 21, 2012 » The Editors' Desk — December 21, 2012

[...] “Whither Whiteness?” by Doug Hartmann. In which our editor considers the coming shift to an American minority-majority and wonders if it’ll change white privilege. [...]

American Children Will be “Majority Minority” by 2018 » Sociological Images — January 10, 2013

[...] at The Society Pages Editors’ Desk, sociologist Doug Hartmann offered the following table. It shows that children under the age of 18 [...]

AMERICAN CHILDREN WILL BE “MAJORITY MINORITY” BY 2018 | Welcome to the Doctor's Office — January 10, 2013

[...] at The Society Pages Editors’ Desk, sociologist Doug Hartmann offered the following table. It shows that children under the age of 18 [...]

How Democrats and Republicans Can Draw Uncommitted Minorities into Politics » Scholars Strategy Network — January 14, 2013

[...] demographic future is clear. Sometime around 2050, today’s racial and ethnic minorities will become the majority. This change will be one of the [...]