Cross-posted at Sociology Lens.

A number of researchers suggest that the marketing and advertising of Gardasil has been aimed at girls and women instead of boys and men. In this post I discuss two contradictory messages aimed at women through these advertisements.

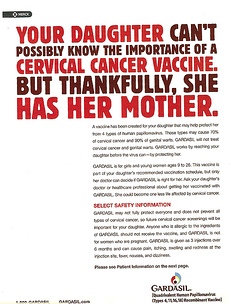

The first type of ad focused around the protection of young girls. The makers of Gardasil imply that being a good parent means vaccinating your daughter and therefore protecting her from cervical cancer (an observation also made here at Sociological Images). For example, one advertisement read, “How do you help your daughter become one less life affected by cervical cancer?” Another advertisement had a similar sentiment, stating “Your daughter can’t possibly know the importance of the cervical cancer vaccine, but thankfully, she has her mother” (source).

This narrative of protectionism is not surprising. In other contexts, like sex education debates, the discourse about adolescent sexuality, and in particular, girls’ sexuality, reveals a desire to protect their “innocence.”

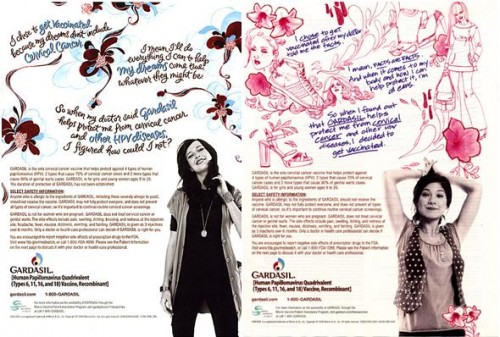

The other type of ad moves away from the narrative of protectionism and focuses on empowerment and choice. One ad stated, “I chose to get vaccinated after my doctor to me the facts” (source). Another ad read, “I chose to get vaccinated because my dreams don’t include cervical cancer” (source).

Instead of focusing on the ways in which girls and women can be protected, the ads suggest that girls and women need to protect themselves. It seems like the advertising department at Merck (the makers of Gardasil) recognize that they needed another strategy if they wanted to appeal to young women who feel empowered about their sex lives.

Instead of focusing on the ways in which girls and women can be protected, the ads suggest that girls and women need to protect themselves. It seems like the advertising department at Merck (the makers of Gardasil) recognize that they needed another strategy if they wanted to appeal to young women who feel empowered about their sex lives.

These two strategies are opposed to one another. One strategy suggests that girls and women need to be protected, while the other strategy relies on the ability of girls and women to be active and educated decision makers. Merck is tapping into two gendered narratives in order to sell to as many people as possible. This is, of course, the way that advertising works. But it does reveal the different, and sometimes contradictory, cultural ideas about women’s sexuality, ideas that advertisers will draw on in order to make a profit.

—————————

Cheryl Llewellyn is a Ph.D. candidate in sociology at Stony Brook University. She writes for Sociology Lens, where you can read her post about the feminization of the Gardasil.

Comments 70

Blabla — December 11, 2012

Well, women should get a vaccine before becoming sexually active. My country's schools vaccine girls around 14 and sooner could be better.

In this scope, I understand why informing and convincing parents matter : they choose. I know it's not done for monetary reasons (and because the vaccine is still new), but vaccinating boys and men would help eradicate much more efficiently the HPV ! ¨¨

Those ads specifically "untarget" men from the discussion.

mandassassin — December 11, 2012

I don't know that the first set of ads has anything at all to do with protecting a girl's "innocence". It's pretty clear that they're talking about protecting your child's health. Which is something that all parents ought to do for their children, when they are too young to really understand and make their own health decisions. I'm just not seeing this as a comment on anyone's sexuality. Am I missing something?

Alison — December 11, 2012

I think you're misinterpreting the first ad. It's aimed at mothers wanting to protect their child's health, not their "innocence". It's encouraging parents to be proactive about their children's health, which is probably a good thing. People who are concerned about "innocence" are fighting against the vaccine.

Of course it's more than a little problematic that it's aimed only at women and girls, and assumes that only mothers care about their children's health.

Gomiville — December 11, 2012

I agree with the other commentators. The first ad seems aimed at mothers because it's targeting a younger demographic for the vaccine, while the latter ads are aimed at the women themselves because it's aimed at an older demographic.

Like Alison says, there's still the issue that the first ad is aimed solely at mothers, rather than parents in general, though I think this *might* be excused for the particular medical issue involved (dad, assuming cis-normative parents, doesn't have a cervix to get cancer with, while mom and daughter share the anatomy involved).

Tusconian — December 11, 2012

Uh. Guardasil is aimed at female-bodied people between 11 and 26 (I think). While to certain people that all sounds just ~*~sewwwww young~*~ there is an ENORMOUS difference between a fifth grader and a woman in her mid twenties. An eleven year old does not have control over her medical choices. An eleven year old SHOULDN'T have complete control over her medical choices. Why would you expect an eleven year old to make informed decisions regarding sexual health and the possibility of cervical cancer when most eleven year olds are not sexually active and probably barely even know what a cervix is? Underage girls do not have complete control over their medical procedures for a reason: because they are not adult women. Twisting your fingers about the "agency" of preteen and teenage "women" is nonsense; they lack agency in such matters because they are children, not because they are girls. Children do not have the knowledge of medical necessities or the mental capability to make a good judgement call in such situations because they are children. However, the vaccine isn't aimed only at children, but at young women. I think it's pretty blatant that the people pictured are adult women; adult women have control over their medical and sexual choices because they are adults. Legally, biologically, and socially, children and adults are not the same thing, and trying to define underage girls as "women" or adult women as "young girls" to make some twisted point doesn't change those facts.

Andrew S — December 11, 2012

As others, the first ad seems to be talking about YOUNG daughters who really, for the most part, don't know what a cervix is let alone how cancer may get there.

Yes, it is protecting their "innocence", perhaps, by suggesting they're so young and innocent they know nothing about sex and how you may get HPV.

The other ads clearly show older teens, perhaps even young adults, in the images.

oofstar — December 11, 2012

where did these ads run? because i'll bet the first were in parenting magazines or magazines for older women and the others in teen magazines or whatever they think 20-something girls read.

there is nothing oppositional about these ads. like everyone else, i think you're off the mark.

also, i think you're abortion/reproduction tag doesn't make sense for this article. not everything sexual is about reproduction.

Anna — December 11, 2012

It's recently been shown to be effective for women up to the age of 45. When I had the vaccine a few years ago, it was still only approved for women up to the age of 26. My doctor told me older women could get it as well, but insurance wouldn't cover it past age 26, and there was not yet enough evidence that it could be effective past that age. In Greece, it is a semi-mandatory vaccine given to girls at the age of 13 ("semi" as guardians retain the legal right not to let their daughter get it).

26 is not an arbitrary age that the medical community selected, by the way. The vaccine was tested almost exclusively on women up to the age of 26, obviously to better limit and control the sample, but also because a woman's likelihood of contracting a kind of HPV grows with each new sexual partner. The reasoning was that most women who are at risk for HPV infections are not ultra-conservative sexually (i.e waiting for marriage to have sex, or already being married and only having one sexual partner), and that by her mid-twenties, women will be more likely of having contracted an HPV infection through her sexual partners. Yes, of course it is possible to contract HPV even if you've only had one sexual partner, but statistics show that it is far more likely if you have multiple sexual partners.

We are talking about, after all, THE most common STD, and many in the medical community claim that most people will be exposed to it at some point. Simply put, if a woman has or had any kind of HPV infection, the vaccine will NOT be effective.

I see nothing wrong with the ads. They have different messages because they are targeting two very different age groups. And yeah, it is about women taking responsibility and precautions for our sexual health, or parents taking measures for their daughters' sexual health. That's what the "appeal" of the vaccine is. It's not some cunning marketing ploy. And of course it is a gendered narrative. The vaccine has narily been approved for boys in most countries, and where it has, it is not yet covered by insurance. And it is an expensive vaccine. This will likely change in the coming years. (Leaving out "father" in the first ad is exclusionary, but while some may disagree with me, I really feel like that's nitpicking.)

Ted_Howard — December 11, 2012

This analysis is bizarre.

The first ad is clearly aimed at mothers who have girls that are not yet sexually active (< age 14? 15?), who usually are responsible for the health decisions of a child. It's fairly rare to see a father manage his children's healthcare, except in the cases of a single father. The point is young girls do not make their health care decisions, hence the ad is directed at their parents. The second ad is clearly aimed at older women - they even show pictures of women who appear to be over the age of 18. At that age a women takes responsibility for her own health care decisions, hence the ad is not going to be about some paternalistic protection. Also, isn't the line "I chose to get vaccinated because my dreams don't include cervical cancer" based on a protective motive? Protecting yourself! Both ads appeal to protective motives, just in a different way. One is about paternalistic protection another is about personal protection. It's clear there is not contradiction here, unless they teach some new-fangled semantic interpretation method at Stony Brook.

Sjcottrell — December 11, 2012

In response to the general voice of previous comments, I would like to note that Dr. Llewellyn isn't condemning the ads. She doesn't call them "problematic" or "troubling" or any other other negative language.

She's just pointing out the differences in the two campaigns. I mean, the messages are using these two pretty standard gender themes of 1) women and girls need to be protected and 2) women have the right to choose for themselves.

That's kind of interesting to me, honestly. That the ad machine has produced these fairly contradictory pitches to sell their product. It underlines the fact that the company is using whatever means it can to get people interested.

Also, I think some people here might be underestimating the weight of the sexual aspect of this issue. Even though the ad copy might not mention the idea of "protecting a girl's sexual innocence," the idea is heavily linked to the product. I doubt that the ad designers were unaware of that attitude.

http://www.theatlanticwire.com/national/2012/10/study-hpv-vaccine-doesnt-turn-girls-sex-maniacs/57941/

Umlud — December 11, 2012

Note: I'm basing my argumentation on the information about age-related efficacy of the HPV vaccine, taken from the CDC's website (http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd-vac/hpv/vac-faqs.htm ).

Based on this information, I think that Merck likely was targeting pre-teens in the first set of ads, because it's within this group that the vaccine is the most potent:

It makes sense to me that, given this information, the first ad would be targeting parents to protect their 11 and 12 year old (or even down to the age of 9 year old) children. Okay, so they mostly have been focusing on protecting girls, even though Gardasil has been approved for use in males, but the maximum effective age-class is actually at an age during which the subjects of the immunization can't really make a well-informed decision (let alone a legally binding independent decision).

I agree that the wording of the ad does overlap strongly with wording that evokes "protection" tropes toward girls' sexuality, but I don't know that it is as simple as merely asserting it to be so, especially when you consider the social implications of how to market a vaccine that is best when administered to pre-pubecent females.

I also agree that the tone of the second set of advertisements is quite different from the first, but it seems that these are likely to be targeted at women (not girls) up to the age of 26 (which is the estimated maximum age of efficacy for Gardasil). Although post-pubecent females are not - at least according to the CDC - the group within which the vaccine is the most effective, the last time I checked, advertising something that has even a hint of a connection to sex is far, FAR easier to do when you target adults - male or female - compared to when you target children, especially girls.

What We Missed — December 11, 2012

[...] the contradictory messaging of Garadasil [...]

Saba — December 11, 2012

But...these are aimed at two different audiences. One is clearly for parents of underage girls and the other is for youn adults. So of course the messages are different.

dragon847 — December 11, 2012

What? One campaign is targeting the parents of girls (children), the other is targeting young women (adults). There's no contradiction here. Girls and women are not equivalent. And the consistent conflation of these groups, I believe, also contributes to the early sexualization of girls and the infantilization of adult women.

Enquire — December 11, 2012

Let's not forget that this vaccination (or product, if you prefer) actually does save lives, unlike majority of other products marketed to women. The ads are produced in order to reduce the incidence of cervical cancer amongst all women, and therefore I think in this case the end more than justifies the means.

Candy — December 12, 2012

It disappoints me to see the commenters in this thread are by and large agreeing with one another.

Jane2responsible — December 12, 2012

From a healthcare perspective I see this as guilting parents. We have to do this every day and with all sorts of vaccines. How do I get a parent who STILL thinks vaccines cause autism to cooperate with me? Tell her she needs to protect her child who could otherwise die from measles. How do I get a parent to consent to the gardisil vaccine? Tell the parents the vaccine protects her child from getting HPV related cancers - (which include head and neck cancers in men and women.) I find this to be what works.

shut up — December 13, 2012

hey everyone just do some coke and yo dont need antibiotics

Ellen — December 13, 2012

I believe that the Author is angered by the fact that Gardasil has gendered ads aimed towards women, but the fact is, Gardasil was designed for women as a vaccine, it has only recently been tested and proven effective for men. The ads are gendered so they appeal to the customers they are designed for. However, as a woman, I do not find this offensive. These are two separate ads directed at two different groups. One towards the mother's of girls, telling them to give their daughters the necessary tools to be empowered in their sexual choices and reproductive health. The other is directed directly at the girls, and again is empowering them to take charge of their reproductive health. Both ads are designed to sell because that is the purpose of ads, however, they do so in an appeal to the strength of women, not their weakness and supposed need for protection. By telling women and mothers, to make the choice, and not men to make the choice for them, they are empowering women to make their own choices, not pandering to the weakness of the female sex.

Haylee — December 13, 2012

I received the HPV vaccine when I was about 14 or 15 and I discussed it with my doctor and my mother. At that age I was not thinking about protecting myself from cervical cancer and was not thinking about empowering myself about my sex life. I got the vaccine because my mother and doctor thought it was a good idea. I think it is a good thing to market to "protecting your daughter" because young girls, who the drug is for, aren't going to be making this decision on their own. Even if it's not their mother who is making the decision, someone who cares about them is. I don't think it is neccessary to focus so much on the mother. But protecting daughters is a good advertisement strategy. I don't feel like it left me unempowered to have that choice basically made for me, I'm thankful.

Rachel — December 14, 2012

This analysis fell rather flat.

Richard Strong — December 18, 2012

What the hell is a cervix?!

Laura — October 29, 2013

This article does a terrible job of making the point it is attempting to make. This space could have better been utilized to discuss the need for a male-centric ad in addition to these. If all men were vaccinated, women wouldn't need to get the vaccine themselves... However, since not all men are, it is indeed smart for women to protect themselves by getting the vaccine in today's world.

I agree with previous commenters that parents DO need to keep watch for health issues and threats that their kids aren't yet aware of. And I don't see anything wrong with an ad that focuses on female empowerment and agency to protect themselves. The threat is real, and therefore so is the need for protection.

If you don't appreciate either of these, I'd like to know how you would advertise this product in an effective manner?

Lastly, unfortunately, if the target market is cervix possessors, I don't really see a "do you possess a cervix?" campaign going over effectively, though I could be wrong. As a researcher, targeting women within the cervix possessing demographic covers over 95% of the target market, so realistically this approach may make the most sense for advertising purposes.

Women Laughing Alone With Vaccine Injection Sites | The Daily News Report — December 17, 2013

[…] though a former Merck ad depicts me as a helpless waif who depends on my mother’s vaccine wisdom to ‘do the […]

Women Laughing Alone With Vaccine Injection Sites | Pakalert Press — December 18, 2013

[…] though a former Merck ad depicts me as a helpless waif who depends on my mother’s vaccine wisdom to ‘do the […]

Women Laughing Alone With Vaccine Injection Sites : Natural Wellness Review — January 7, 2014

[…] though a former Merck ad depicts me as a helpless waif who depends on my mother’s vaccine wisdom to ‘do the […]