Apparently for the last several presidential elections 7-11 has had a “7-Election” marketing campaign, in which they offer blue and red coffee cups and customers “vote” by choosing one or the other. Here is a screenshot from the 7-Election 2008 website:

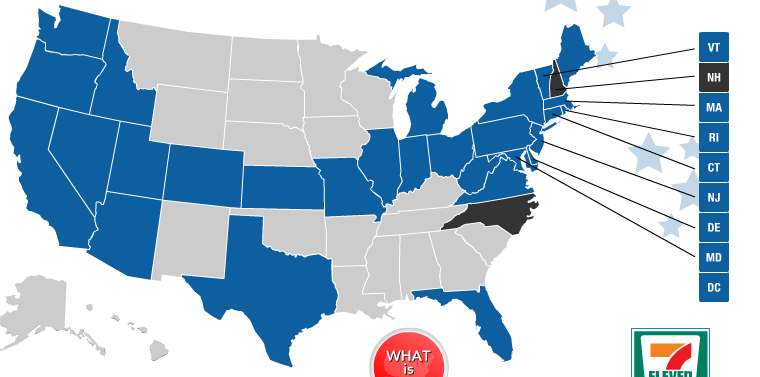

You can go to the website and see the “voting” results map (current as of this morning), which shows two states at 50/50 and every other state going for Obama:

If you go to the actual website, you can hover over each state and see what the % breakdown is.

Now, in and of itself, I just thought this was slightly interesting as an example of the commodification of political choice (“express your voting preference through a coffee cup!”), and I thought it could be used as an example of made-up statistics that are entirely meaningless. For instance, at the 7-11 near my house, I noticed they only have blue cups available, so it would be impossible to “vote” for McCain. Anyone with just some basic common sense could think of tons of problems with this as a real methodology–it didn’t even really seem worth my time to go into much detail about why a poll based on sale of coffee cups is unscientific and stupid.

But then I noticed something on the website: according to the website, results are reported weekly in USA Today (although I wasn’t able to find links to any weekly reports, which seemed odd). I know USA Today isn’t considered a high-quality newspaper by a lot of people, but still, it’s at least ostensibly reporting news. The 7-Election website also has a link to CNN, so perhaps they are partnering with them, too. Editor & Publisher ran a story on it. The results of a marketing scheme to sell coffee is being treated as news. I’m going to try to use it in class to discuss how things get defined as “newsworthy,” and who sets the agenda for what we’re going to talk about. Here we have a company getting free publicity for its marketing promotion because that marketing promotion has been declared “news.” What important information about the world is being ignored in favor of this? How does treating this as newsworthy legitimize it, as though these statistics are meaningful or accurate? Does that increase sales for 7-11?

I found a lot of comments on blogs where people claimed that after hearing about this campaign, they went out and bought coffee just to “vote” for their preferred candidate, and a few who said they refused to buy coffee because the store was out of the cups they wanted. I find this entire thing incredibly bizarre, and I don’t see why news outlets and individuals are buying into the idea that this is anything other than a way to convince more people to buy 7-11 coffee.

NEW! In our comments, Penny pointed out that Baskin Robbins does the same thing. Here are the results from this suspicously delicious poll as of the morning of Nov. 4th: