In her book The Body Project: An Intimate History of American Girls, Joan Jacobs Brumberg has a chaptered titled “Perfect Skin” in which she looks at the rise of acne as a significant concern among adolescent girls. Because pimples and blackheads were believed by some people to be a sign of immorality–masturbation, lascivious thoughts, or promiscuity–both teenagers and their parents were quite distressed at the appearance of teen acne. Though teens had long been concerned about their appearances, the widespread use of mirrors in bathrooms starting in the Victorian Era gave them many more opportunities to examine their faces and find themselves lacking. And girls tended to be more concerned about their faces than boys, perhaps because girls were judged more harshly for any perceived sexual immorality. A whole industry arose to sell generally useless products to teens, particularly girls, to cure their acne.

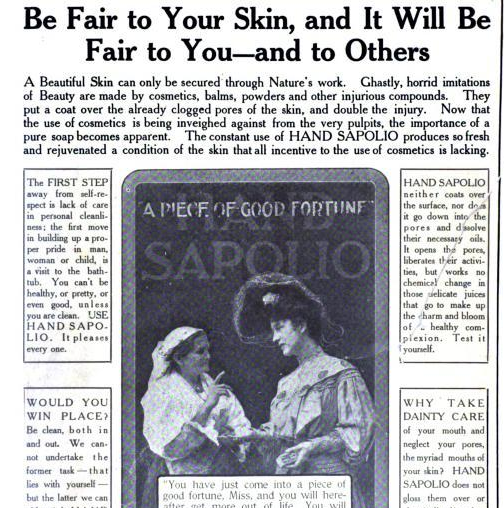

Marketers for soap and other products used concerns about morality in their ads. Here is an ad for Hand Sapolio, a popular soap in the early 1900s (found in a 1906 issue of McClure’s Magazine):

Notice how the text in the top box mentions that cosmetics, which might be used to cover pimples, were being “inveighed against from the very pulpits,” meaning good moral girls couldn’t use cosmetics to hide their acne. Also I like how the title (“Be Fair to Your Skin, and It Will Be Fair to You–and to Others”) implies that if you aren’t fair to your skin, it is going to do something dreadful to the people around you…presumably busting out into a hideous display of pimples that will pain people to look upon.

I zoomed in and did a couple of smaller screen captures of some sections of the text that also stress morality or “goodness”:

Be clean, both in and out. We cannot undertake the former task–that lies with yourself–but the latter we can aid with HAND SAPOLIO.

This section of text makes it clear that good skin is essential for popularity, at least among the “best” people:

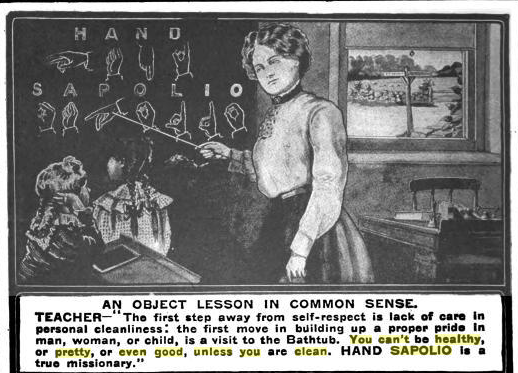

This Hand Sapolio ad (from a 1903 issue of New England Magazine), sums it up:

The first step away from self-respect is lack of care in personal cleanliness: the first move in building up a proper pride in man, woman, or child, is a visit to the Bathtub. You can’t be healthy, or pretty, or even good, unless you are clean. HAND SAPOLIO is a true missionary.

So there we see a connection being made between having good skin and being “good,” which means that, like missionaries who help save heathens, Hand Sapolio is a “missionary” spreading moral goodness and self-respect. Because what could build up self-respect more than being told that if you have less than perfectly clean skin, you can’t be pretty or good?

These could be useful for discussions of how physical appearances were steadily connected to ideas of morality and how biological processes, like getting pimples in adolescence, were turned into diseases that required (often expensive) intervention to “cure.” They could also be good for a discussion of marketing, particularly how ideas of morality were tied to particular products, such that goodness was commodified–by buying the item, you were buying goodness.