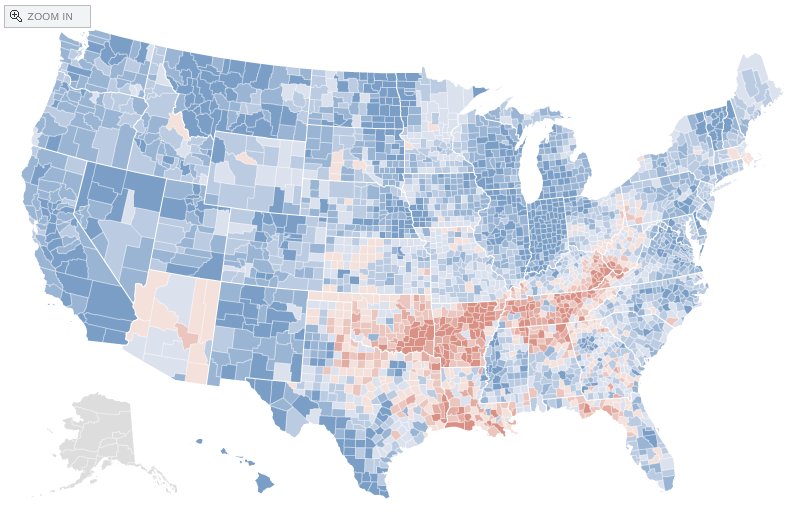

Many of you may have seen the image below. It compares the 2004 to the 2008 vote and shows, by color, how much more Democratic (blue) or Republican (red) each county leaned in 2008. In essence, compared to 2004, in this election Democrats increased the proportion of the vote that they received in most counties.

You may not have seen, however, this next image. This next image shows the same data but compares 1992 to 2008. Looking across those sixteen years it is clear that, while this last election may have looked good for Democrats, the last five have moved the country significantly to the right. If you are a Democrat, then, this election is one step forward after 10 steps back. And, if you are a Republican, it may very well be a very small setback.

(Data from the New York Times; images found here.)