In my post a few weeks back about stuff kids bring to college, I had a photo of a teddy bear lying atop a pile of belongings that included pink bed linens. Obviously, it belonged to a girl. (There was a purse in the picture, but even without it. . . .)

A couple of days later, Lisa at Sociological Images had a post reminding us that pink was once the color for boys. She linked to an article by Ben Goldacre in the Guardian.

The Sunday Sentinel in 1914 told American mothers: “If you like the colour note on the little one’s garments, use pink for the boy and blue for the girl, if you are a follower of convention.”

Goldacre uses this bit of history to debunk the claim recently made by evolutionary psychologists that girls’ preference for pink was an outcome of evolution.

But what about the teddy bear? Isn’t there something feminine, a maternal instinct perhaps, that leads girls to keep these soft, childhood objects? It is only girls, right?

Wait, now I remember seeing NYC sanitation trucks with a teddy bear mounted on the grill like a bowsprit mermaid. And Sebastian Flyte in Brideshead Revisited who takes his bear Aloysius with him to Oxford.

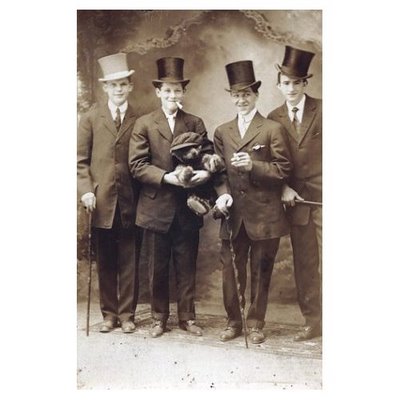

Now there’s a DVD* about a Teddy bear snapshot exhibition by Canadian Ydessa Hendeles – thousands of photos from the early twentieth century of people posing with their bears. And it’s not just girls.

*The DVD is of a documentary film by Agnès Varda, who interviews the visitors to the exhibit.

Hat tip to Magda

Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.