Stephen W. sent us this picture of the “Hispanic” foods aisle at a Walmart in Sioux Falls, South Dakota:

Why is this odd?

The word “Hispanic” was actually invented by the U.S. government to mean Spanish-speaking. The government invented it for the census because they wanted to be able to label and identify all Spanish speakers. “Hispanic,” then, unlike the terms “Latino” or “Chicano,” is not an identity that originated among those to whom it applies. Further, though it is sometimes used as a euphemism for “Mexican” or “Latino,” Spanish is only spoken in Latin America because of the conquest of parts of Latin America by Spain.

Given the history and use of this term, what would “Hispanic” food be?! (According to Walmart, it’s salsa and tacos.)

NEW: Another use of the term “Hispanic.” This time on a bag of peanuts passed out on a Southwest Airlines flight.

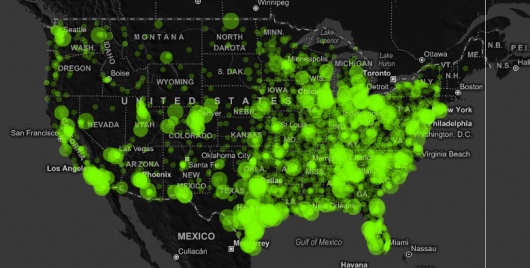

From a press release by Southwest Airlines about their celebration of Southwest Airlines:

Southwest Airlines shares its passion for Hispanic Heritage Month with our internal and external Customers by hosting celebrations in our Hispanic focus markets. Local Employees kick off the festivities by partnering with local organizations, and at airports, with gate games, Mariachi music, authentic foods, and distributing commemorative T-shirts and lapel pins emblazoned with our Hispanic Heritage Month message “Celebremos Tu Herencia,” “We Celebrate Your Heritage.” Hispanic Heritage month posters also are on display during this month-long celebration. Finally, be on the lookout for Southwest’s Hispanic Heritage Month specialty packaged peanuts! (emphasis mine)

Thanks to Stephen W. for this link, too!