Cross-posted at Montclair SocioBlog.

I’m not sure what effect prime-time sitcoms have on the general public. Very little, I suspect, but I don’t know the literature on the topic. Still, it’s surprising how many people with a similar lack of knowledge assume that the effect is large and usually for the worse.

Isabel Sawhill, is a serious researcher at Brookings; her areas are poverty and inequality. Now, in a Washington Post article, she, says that Dan Quayle was right about Murphy Brown.

Some quick history for those who were out of the room — or hadn’t yet entered the room: In 1992, Dan Quayle was vice-president under Bush I. Murphy Brown was the title character on a popular sitcom then in its fourth season — a divorced TV news anchor played by Candice Bergen. On the show, she got pregnant. When the father, her ex, refused to remarry her, she decided to have the baby and raise it on her own.

Dan Quayle, in his second most famous moment,* gave a campaign speech about family values that included this:

Bearing babies irresponsibly is simply wrong… Failing to support children one has fathered is wrong… It doesn’t help matters when prime-time TV has Murphy Brown, a character who supposedly epitomizes today’s intelligent, highly paid professional woman, mocking the importance of fathers by bearing a child alone and calling it just another lifestyle choice.

Sawhill, citing her own research and that of others, argues that Quayle was right about families: children raised by married parents are better off in many ways — health, education, income, and other measures of well-being — than are children raised by unmarried parents whether single or together.**

But Sawhill also says that Quayle was right about the more famous part of the statement – that “Murphy Brown” was partly to blame for the rise in nonmarried parenthood.

Dan Quayle was right. Unless the media, parents and other influential leaders celebrate marriage as the best environment for raising children, the new trend — bringing up baby alone — may be irreversible.

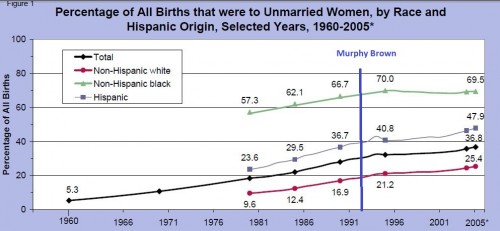

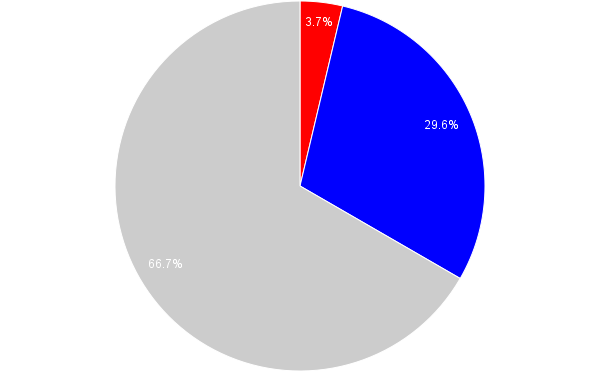

Sawhill, following Quayle, gives pride of place to the media. But unfortunately, she cites no evidence on the effects of sitcoms or the media in general on unwed parenthood. I did, however, find a graph of trends in unwed motherhood. It shows the percent of all babies that were born to unmarried mothers. I have added a vertical line to indicate the Murphy Brown moment.

The “Murphy Brown” effect is, at the very least, hard to detect. The rise is general across all racial groups, including those who were probably not watching a sitcom whose characters were all white and well-off. Also, the trend begins well before “Murphy Brown” ever saw the light of prime time. So 1992, with Murphy Brown’s fateful decision, was no more a turning point than was 1986, for example, a year when the two top TV shows were “The Cosby Show” and “Family Ties,” sitcoms with a very low rate of single parenthood and, at least for “Cosby,” a more inclusive demographic.

————————

* Quayle’s most remembered moment: when a schoolboy wrote “potato” on the blackboard, Quayle “corrected” him by getting him to add a final “e” – “potatoe.” “There you go,” said the vice-president of the United States approvingly. (A 15-second video is here.)

** These results are not surprising. Compared with other wealthy countries, the US does less to support poor children and families or to ease the deleterious effects on children who have been so foolhardy as to choose poor, unmarried parents.