Cross-posted at OrgTheory.

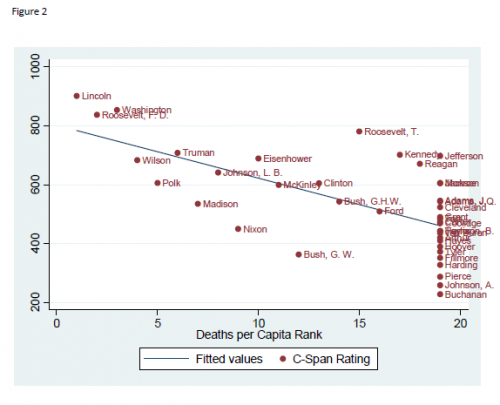

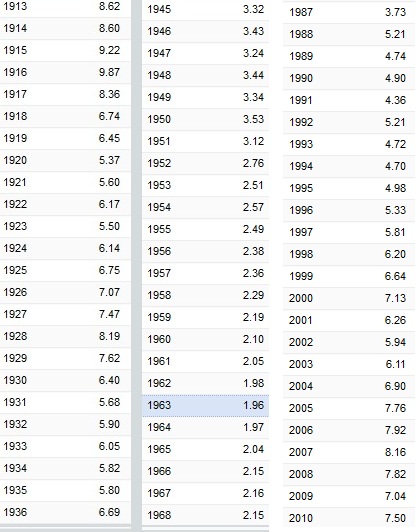

David Henderson and Zachary Gouchenour have a paper on the topic of presidential ratings. The finding is simple. American war casualties, as a fraction of the population, positively correlate with how historians rate U.S. presidents. More death = better presidents. The regression model includes some controls, like economic growth. Here’s the chart:

This is consistent with sociological research on state building, which has traditionally linked wars, bureaucratic growth, and tax collection. See, for example, Charles Tilly’s classic work “Warmaking and Statemaking as Organized Crime.” My one criticism of the paper is that there is no measure in the regression that controls for “big legislation” (i.e., New Deal). Historians like law passing and it might account for some variation. I have a hunch that is how variation on the right hand side of the figure would be explained.

Henderson and Gouchenour then spin out the policy implication. Greatness rankings by historians may prompt presidents to start more wars. The historians may have more blood on their hands than we care to admit.

Adverts: From Black Power/Grad Skool Rulz

—————————

Fabio Rojas is an Associate Professor of Sociology at Indiana University. He is the author of two books: From Black Power to Black Studies: How a Radical Social Movement Became an Academic Discipline and Grad Skool Rulz: Everything You Need to Know about Academia from Admissions to Tenure. Rojas’ academic research addresses political sociology, organizational analysis, and computer simulations.