Cross-posted at Reports from the Economic Front.

It’s election season and Republicans and Democrats are working hard to demonstrate that they support dramatically different policies for rejuvenating the economy.

While the Democratic Party’s call for more government spending makes far more sense than the Republican Party’s call for cuts in government spending (see below), the resulting back and forth hides the far more serious reality that our existing economic system no longer appears capable of supporting meaningful social progress for the great majority of Americans.

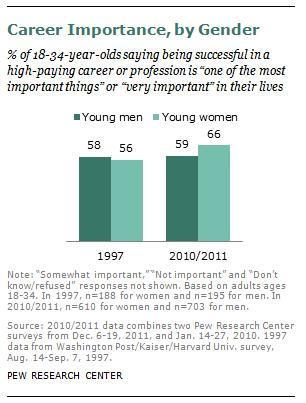

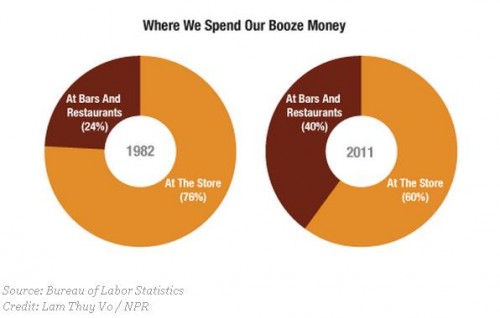

The chart below helps to highlight our economy’s worsening stagnation tendencies. Each point shows the 10 year annual average rate of growth and the chart reveals a decade long growth trend that is moving sharply downward.

As David Leonhardt explains:

The economy’s recent struggles arguably began in late 2001, when a relatively mild recession ended and a new expansion began. The problem with this new recovery was that it wasn’t especially strong. From the fourth quarter of 2001 through the fourth quarter of 2007 (when the financial crisis began), the economy grew at an average annual rate of only 2.7 percent. By comparison, the average annual growth rate of both the 1990s and 1980s expansions exceeded 3.5 percent.

This mediocre expansion was followed by the severe recession and weak recovery brought on by the financial crisis. The combined result is that, in recent years, the economy has posted its slowest 10-year average growth rates since the Commerce Department began keeping statistics in 1947.

In fact, the economic growth figures for the period 1995 to 2007 were artificially propped up by a series of bubbles, first stock and then housing. Once those bubbles popped, average growth rates began steadily falling.

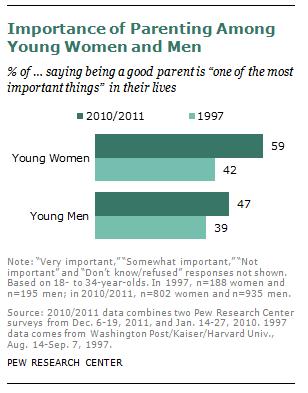

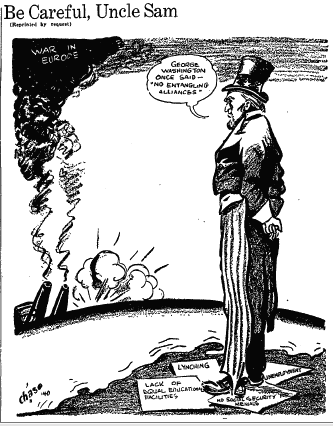

The weakness (and unbalanced nature) of our current weak recovery is well captured in the following chart from Catherine Rampell, which compares the percent change in various indicators in the current recovery (which began in June 2009) with previous post-war recoveries. The first point to stress is that the current recovery lags the average in all indicators but one: corporate profits. The second is that government spending has actually been falling during the current recovery, no doubt one reason that the percent increase in so many indictors remains below the average in previous recoveries; the public sector is actually smaller today than it was three years ago.

The relative strength in the performance of corporate profits helps to explain why the two established political parties feel no real pressure to focus on our long term economic problems; corporations just don’t find the current situation problematic despite the economy’s weak overall economic performance.

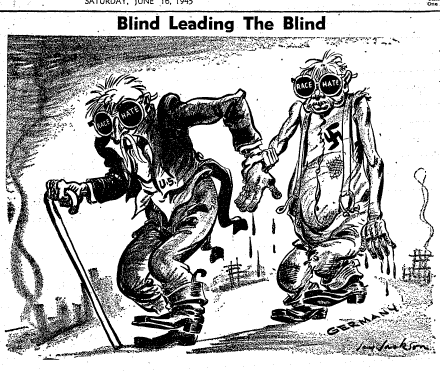

Even more telling of the growing class divide is the explosion in income inequality over the last thirty years, which is illustrated in the following chart.

In other words, while corporations have succeeded in raising profits at the expense of wages, those in the top income brackets have been even more successful in raising their income at the expense of almost everyone else. Notice, for example, that median household income in 2010 is roughly where it was in the late 1980s while the median income of the top households racked up impressive gains. Thus, the very wealthy have every reason to do what they are currently doing, which is using their wealth to ensure that candidates restrict their economic proposals to reforms that will do little to change the existing system.

The takeaway: without a mass movement demanding change, election debates are unlikely to seriously address our steady national economic decline.