Americans are familiar with seeing the phrase “In God We Trust” on our paper money. The motto is, indeed, the official United States motto. It wasn’t always that way, however. While efforts to have the phrase inscribed on U.S. currency began during the Civil War, it wasn’t until 1957 that it appeared on our paper money, thanks to a law signed by President Eisenhower.

1956:

1957:

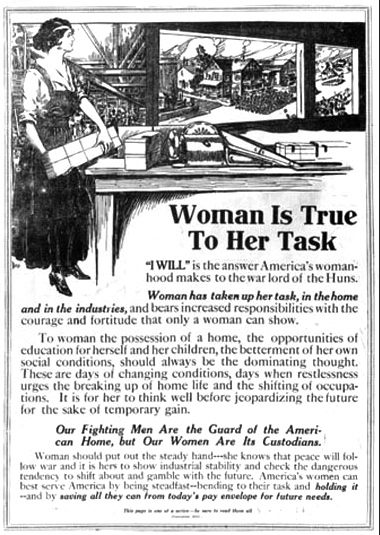

The motto wasn’t simply added in order to please God-fearing Americans, but instead had a political motivation. The mid- to late-1950s marked an escalation in the Cold War between the U.S., the Soviet Union, and their respective allies. In an effort to claim moral superiority and demonize the communist Soviet Union, the U.S. drew on the association of communism with atheism. Placing “In God We Trust” on the U.S. dollar was a way to establish the United States as a Christian nation and differentiate them from their enemy (source).

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.