Originally posted at Family Inequality.

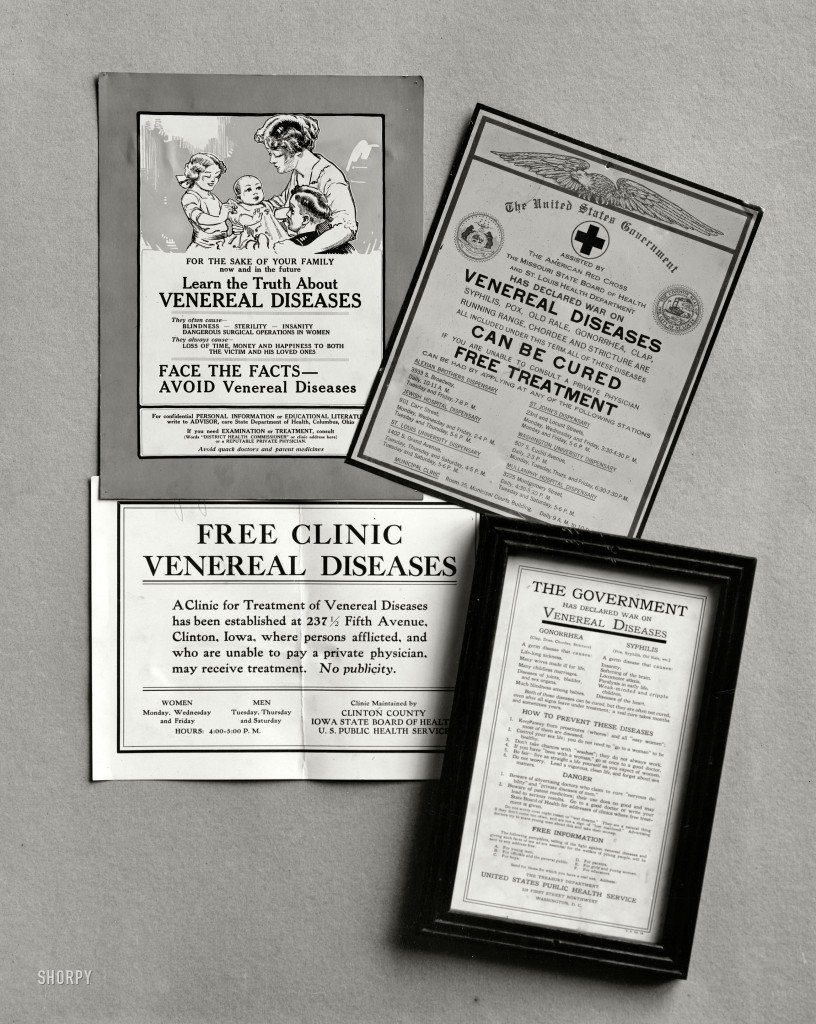

It looks like the phrase “start a family” started to mean “have children” (after marriage) sometime in the 1930s and didn’t catch on till the 1940s or 1950s, which happens to be the most pro-natal period in U.S. history. Here’s the Google ngrams trend for the phrase as percentage of all three-word phrases in American English:

Searching the New York Times, I found the earliest uses applied to fish (1931) and plants (1936).

Twitter reader Daniel Parmer relayed a use from the Boston Globe on 8/9/1937, in which actress Merle Oberon said, “I hope to be married within the next two years and start a family. If not, I shall adopt a baby.”

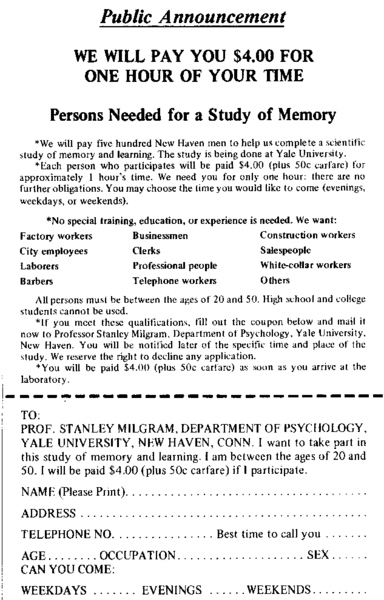

Next appearance in the NYT was 11/22/1942, in a book review in which a man marries a woman and “brings her home to start a family.” After that it was 1948, in this 5/6/1948 description of those who would become baby boom families, describing a speech by Ewan Clague, the Commissioner of Labor Statistics, who is remembered for introducing statistics on women and families into Bureau of Labor Statistics reports. From NYT:

That NYT reference is interesting because it came shortly after the first use of “start a family” in the JSTOR database that unambiguously refers to having children, in a report published by Clague’s BLS:

Trends of Employment and Labor Turn-Over: Monthly Labor Review, Vol. 63, No. 2 (AUGUST 1946): …Of the 584,000 decline in the number of full-time Federal employees between June 1, 1945 and June 1, 1946, almost 75 percent has been in the women’s group. On June 1, 1946, there were only 60 percent as many women employed full time as on June 1, 1945. Men now constitute 70 percent of the total number of full-time workers, as compared with 61 percent a year previously. Although voluntary quits among women for personal reasons, such as to join a veteran husband or to start a family, have been numerous, information on the relative importance of these reasons as compared with involuntary lay-offs is not available…

It’s interesting that, although this appears to be a pro-natal shift, insisting on children before the definition of family is met, it also may have had a work-and-family implication of leaving the labor force. Maybe it reinforced the naturalness of women dropping out of paid work when they had children, something that was soon to emerge as a key battle ground in the gender revolution.

Philip N. Cohen, PhD is a professor of sociology at the University of Maryland, College Park. He writes the blog Family Inequality and is the author of The Family: Diversity, Inequality, and Social Change. You can follow him on Twitter or Facebook.

Note: Rose Malinowski Weingartner, a student in Cohen’s graduate seminar last year, wrote a paper about this concept, which helped him think about this.

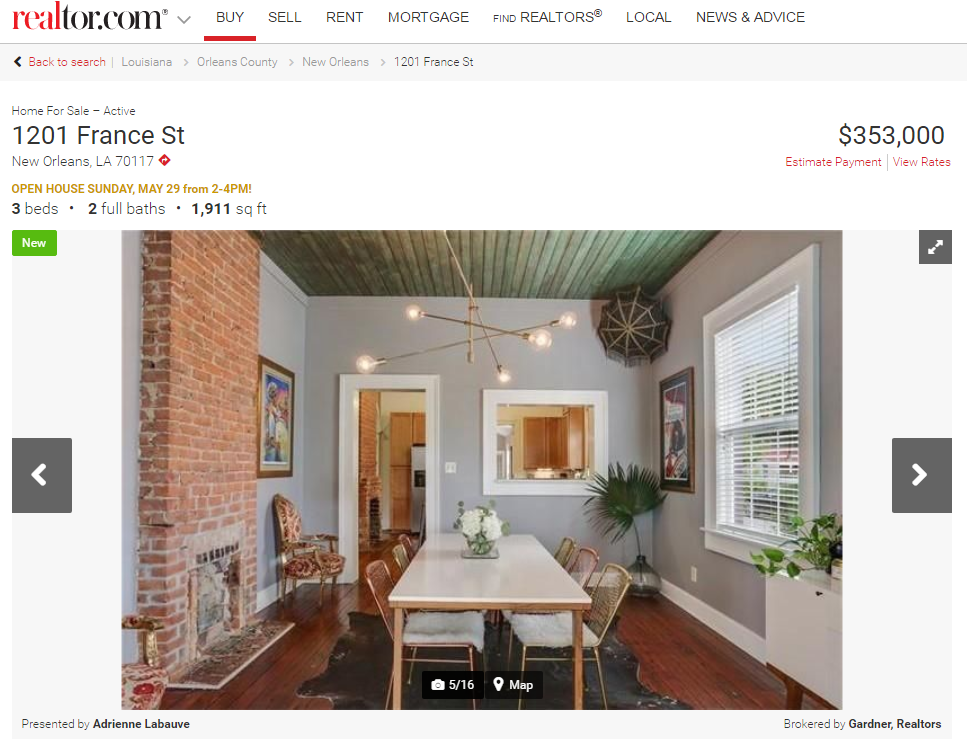

The dining rooms are coming. It’s how I know my neighborhood is becoming aspirationally middle class.

The dining rooms are coming. It’s how I know my neighborhood is becoming aspirationally middle class.