One of the important conversations that has began in the wake of Dylann Roof’s racist murder in South Carolina has to do with racism among members of the Millennial generation. We’ve placed a lot of faith in this generation to pull us out of our racist path, but Roof’s actions may help remind us that racism will not go away simply by the passing of time.

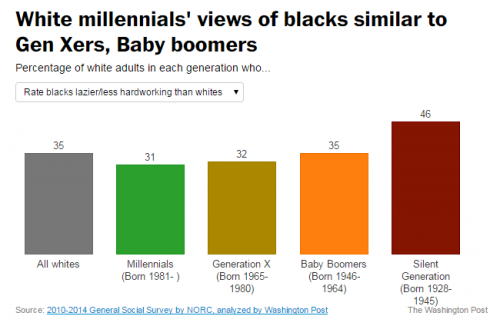

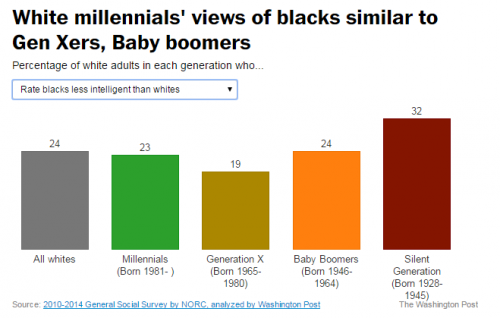

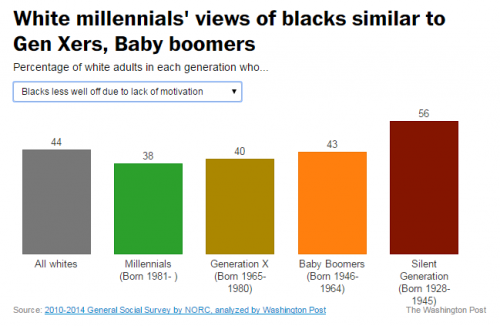

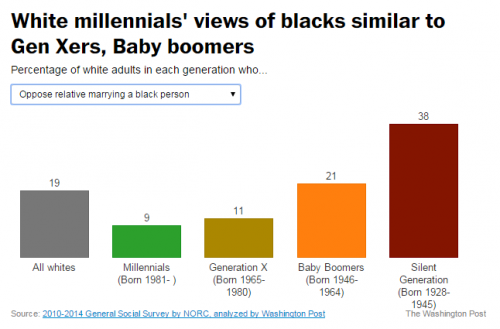

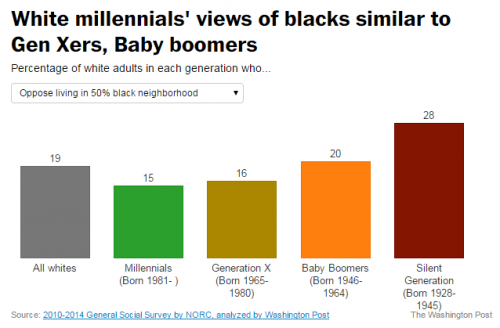

In fact, data from the General Social Survey — one of the most trusted social science data sets — suggests that Millennials are failing to make dramatic strides toward a non-racist utopia. Scott Clement, at the Washington Post, shows us the data. Attitudes among white millennials (in green below) are statistically identical to whites in Generation X (yellow) and hardly different from Baby Boomers on most measures (orange). Whites are about as likely as Generation X:

- to think that blacks are lazier or less hardworking than whites

- to think that blacks have less motivation than whites to do well

- to oppose living in a neighborhood that is 50% or more black

- to object if a relative marries a black person

And they’re slightly more likely than white members of Generation X to think that blacks are less intelligent than whites. So much for a Millennial rescue from racism.

All in all, white millennial attitudes are much more similar to those of older whites than they are to those of their peers of color.

***

At PBS, Mychal Denzel Smith argues that we are reaping the colorblindness lessons that we’ve sowed. Millennials today may think of themselves as “post-racial,” but they’ve learned none of the skills that would allow them to get there. Smith writes:

Millennials are fluent in colorblindness and diversity, while remaining illiterate in the language of anti-racism.

They know how to claim that they’re not racist, but they don’t know how to recognize when they are and they’re clueless as to how to actually change our society for the better.

So, thanks to the colorblindness discourse, white Millennials are quick to see racism as race-neutral. In one study, for example, 58% of white millennials said they thought that “reverse racism” was as big a problem as racism.

Smith summarizes the problem:

For Millennials, racism is a relic of the past, but what vestiges may still exist are only obstacles if the people affected decide they are. Everyone is equal, they’ve been taught, and therefore everyone has equal opportunity for success. This is the deficiency found in the language of diversity. … Armed with this impotent analysis, Millennials perpetuate false equivalencies, such as affirmative action as a form of discrimination on par with with Jim Crow segregation. And they can do so while not believing themselves racist or supportive of racism.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.