Flashback Friday.

U.S. women of color have historically been the victims of forced sterilization. Sometimes women were sterilized during Cesarean sections and never told; others were threatened with termination of welfare benefits or denial of medical care if they didn’t “consent” to the procedure; teaching hospitals would sometimes perform unnecessary hysterectomies on poor women of color as practice for their medical residents. In the south it was such a widespread practice that it had a euphemism: a “Mississippi appendectomy.”

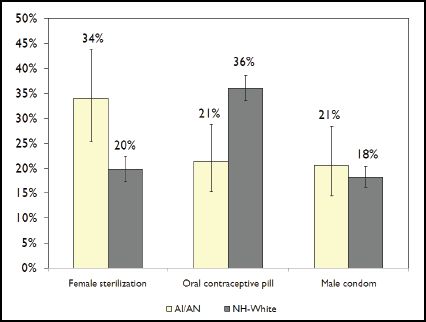

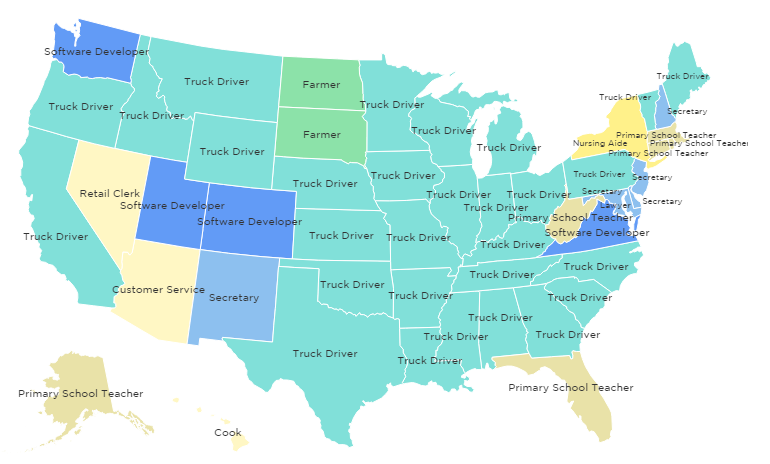

Interestingly, today populations that were subject to this abuse have high rates of voluntary sterilization. A recent report by the Urban Indian Health Institute included data showing that, compared to non-Hispanic white women (in gray), American Indian and Alaskan Native women (in cream) have very high rates of sterilization:

Iris Lopez, in an article titled “Agency and Constraint,” writes about what she discovered when she asked Puerto Rican women in New York City why they choose to undergo sterilization.

During the U.S. colonization of Puerto Rico, over 1/3rd of all women were sterilized. And, today, still, Puerto Rican women in both Puerto Rico and the U.S. have “one of the highest documented rates of sterilization in the world.” Two-thirds of these women are sterilized before the age of 30.

Lopez finds that 44% of the women would not have chosen the surgery if their economic conditions were better. They wanted, but simply could not afford more children.

They also talked about the conditions in which they lived and explained that they didn’t want to bring children into that world. They:

…talked about the burglaries, the lack of hot water in the winter and the dilapidated environment in which they live. Additionally, mothers are constantly worried about the adverse effect that the environment might have on their children. Their neighborhoods are poor with high rates of visible crime and substance abuse. Often women claimed that they were sterilized because they could not tolerate having children in such an adverse environment…

Many were unaware of other contraceptive options. Few reported that their health care providers talked to them about birth control. So, many of them felt that sterilization was the only feasible “choice.”

Lopez argues that, by contrasting the choice to become sterilized with the idea of forced sterilization, we overlook the fact that choices are primed by larger institutional structures and ideological messages. Reproductive freedom not only requires the ability to choose from a set of safe, effective convenient and affordable methods of birth control developed for men and women, but also a context of equitable social, political and economic conditions that allows women to decide whether or not to have children, how many, and when.

Originally posted in 2010. Cross-posted at Ms.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.