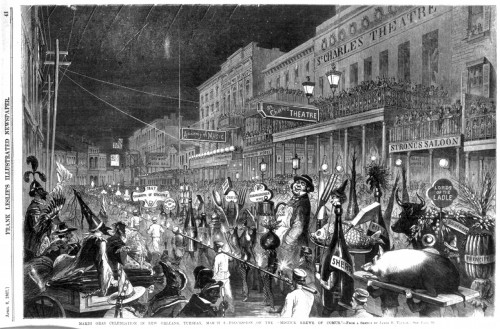

The first Mardi Gras parade New Orleans was held in 1856, over 150 years ago. Today there are, by my count, sixty-eight official Mardi Gras parades in New Orleans and the vicinity. No doubt there are many more informal groups. Each is a private organization, typically still called krewes, wholly funded by its members.

In this sense, Mardi Gras in New Orleans is truly a product of locals who choose to play a role in creating its magic every year. That is, unlike other spectacles — like the city of Las Vegas or the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade — Mardi Gras in New Orleans is a non-corporate holiday facilitated, but not put on by, the city or state government. Even in light of it’s oppressive past and present, it is truly one of the most purely generous, creative, and authentic things I have ever had the pleasure to observe.

Understanding why there are so many parades is part of the story.

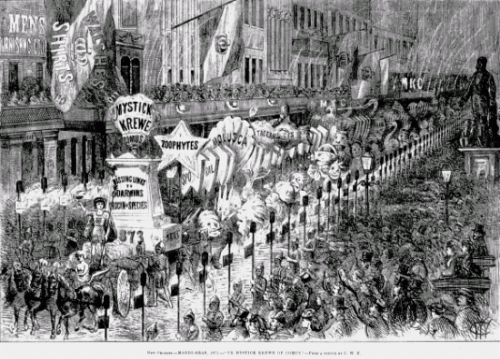

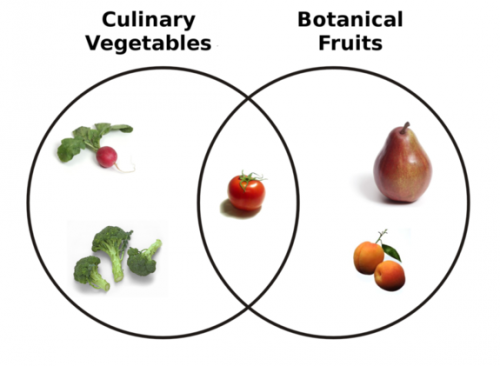

First, krewes have traditionally been segregated by race and gender. New krewes have formed to enable the participation of excluded groups (Zulu 1909, Iris 1917) or integrate the tradition (e.g., Orpheus 1993).

Krewes have also emerged as commentary on this sort of exclusion. The Krewe of Tucks was started by two white male Loyola students in 1969. They wanted to parade as flambeaux carriers — a nod to the original form of parades in which slaves or free men of color carried flames through the streets to illuminate the floats — but were denied. No white person had ever carried the flambeaux.

Annoyed, they started their own parade aimed at mocking the whole parade tradition. Their king sits on a toilet throne and to this day they TP the city in toilet paper as they parade through the streets.

Other parades simply reflect the unending creativity and ingenuity of the people of New Orleans. Responding to the increasing grandeur of Mardi Gras floats over time, ‘tit Rex (as in “petite”) decided to go miniature. Every year, members build tiny floats on a theme and parade them through the Marigny neighborhood. The theme in 2013? “Wee the people.”

‘tit Rex:

Flickr Creative Commons, Chuck Robinson

Not enough sci-fi in the super krewes? There is the Krewe of Chewbacchus — riffing off the famous Krewe of Bacchus. These BacchanAliens offer an intergalactic parade, tripping down the streets of New Orleans with a Bar-2-D2 and other creations.

Chewbacchus:

Flickr Creative Commons, C. Paul Counts

Other parades came about to serve neighborhoods or individuals who were isolated geographically or by mobility. The Krewe of Thoth (1948) was founded in order to offer a parade to the residents of 14 institutions, off the typical parade route, that served people with illnesses or disabilities, bringing Mardi Gras to those who couldn’t come to it. Other krewes emerged simply to serve neighborhoods that tourists rarely visit.

Images: Flickr Creative Commons, James Cage

So there are the stories of a few Mardi Gras krewes, helping to explain the bounty of parades available to enjoy in New Orleans. If you have any favorites, please add them in the comments!

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.