Cross-posted at Ms.

Kelly V. suggested that I check out the book Traffic: Why We Drive the Way We Do (and What It Says about Us), by Tom Vanderbilt. The book is fascinating, covering everything from individual-level psychological and perceptual factors that affect our driving to system-level issues like why building additional roads often simply creates more traffic rather than alleviating it.

Among other things, it turns out that there are clear gender patterns in our driving; in particular, women do more driving as part of their family responsibilities. As Alan Pisarski, a traffic policy consultant, explains,

If you look at trip rates by male versus female, and look at that by size of family…the women’s trip rates vary tremendously by size of family. Men’s trip rates look as if they didn’t even know they had a family. The men’s trip rates are almost independent of family size. What it obviously says is that the mother’s the one doing all the hauling. (p. 135)

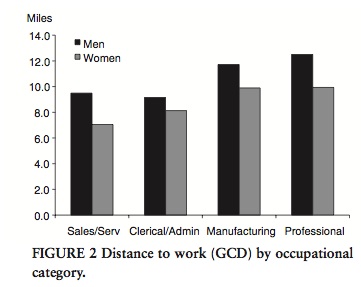

Nancy McGuckin and Yukiko Nakamoto looked at “trip chaining,” or making short stops on the way to or from work. They report that women tend to work closer to home (measured “as the crow flies,” or the great circle distance — GCD) than men in the same occupational categories (McGuckin and Nakamoto, p. 51)):

Research suggests a couple of possibilities for this pattern. Women, taking into account their family responsibilities, may look for closer jobs than men do so it will be easier to balance work and home life. It may also be that the types of jobs women are more likely to hold are more decentralized than men’s jobs and so more likely to be found closer to residential neighborhoods (although the graph above is broken down by occupational category, we see significant gender segregation in jobs within those broad categories).

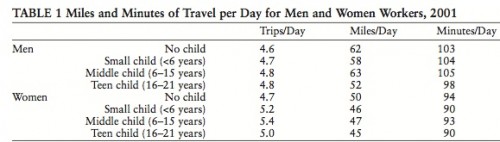

Overall, men drive more total miles, and spend more time driving, per day, but women make more trips, particularly once they have children (p. 51):

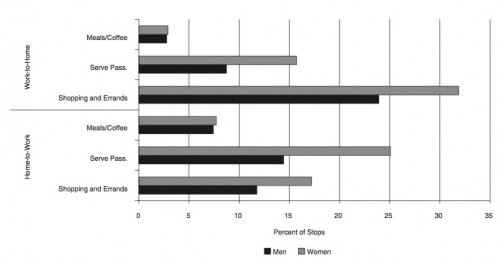

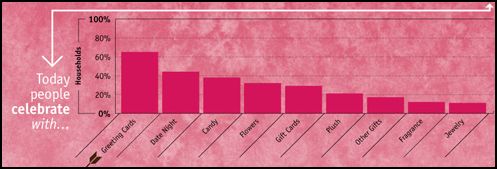

Women are more likely to engage in trip chaining, and men and women differ in the types of stops they make. Men and women both stop to grab meals or coffee for themselves (in fact, the increase in these types of stops by men is so striking it earned a name, the “Starbucks effect”). However, more of the stops women make are to “serve passengers” — that is, going somewhere only because the passenger needs to, such as dropping a child off at school or childcare — or to complete shopping or family errands (p. 54):

Overall, 2.7 million men and 4.3 million women pick up or drop off (or both) a child during their work commute, according to federal data. Among households with two working parents who commute, women make 66% of the trips for drop offs/pick ups (p. 53)

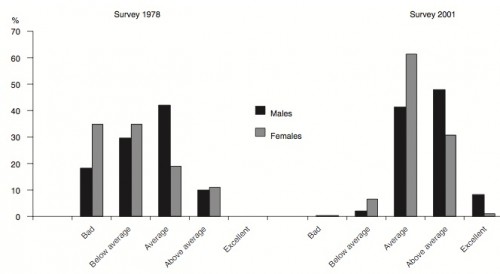

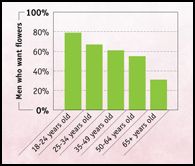

This next graph isn’t related, but I’m throwing it in as a bonus. Sirkku Laapotti found that in both 1978 and 2001, men rated their own driving skills higher, on average, than women rated theirs…but both sexes thought they were way better drivers than people in 1978 did:

[Both papers are from Research on Women’s Issues in Transportation — Report of a Conference. Volume 2: Technical Papers. Conference Proceedings 35 (2005). Washington, D.C.: Transportation Research Board. The McGuckin and Nakamoto paper, “Differences in Trip Chaining by Men and Women,” is found on p. 49-56. Laapotti’s paper, “What Are Young Female Drivers Made Of? Differences in Driving Behavior and Attitudes of Young Women and Men in Finland,” is on p. 148-154.]