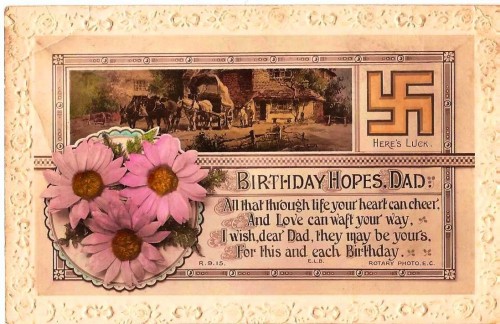

We have posted in the past about pre-World War II uses of the swastika as a symbol of good luck, a meaning that the Nazis’ appropriation of the swastika makes nearly inconceivable today. Matthieu S., who teaches anthropology at Vanier College in Montreal, sent in another example, a scan of a postcard he owns that was printed in the 1920s. The postcard, meant for a dad’s birthday, also includes pink-tinted flowers — evidence of a time when pink was considered a perfectly appropriate color for men and boys:

World War II and the atrocities of the Nazi party obviously significantly changed interpretations of both the formerly-benign swastika and the color pink. Pink wasn’t abandoned altogether, as the swastika was, but the Nazi’s use of pink to label gay and lesbian prisoners led pink to be stigmatized as effeminate and, thus, an inappropriate color for men…and over time it instead became the epitome of symbols of femininity.