Last week Kay Hymowitz (who sometimes works out of a PO Box rented by Brad Wilcox) wrote the following in the LA Times:

As far back as the 1970s, family researchers began noticing that… [b]oys from broken homes were more likely than their peers to get suspended and arrested… And justice experts have long known that juvenile facilities and adult jails overflow with sons from broken families. Liberals often assume that these kinds of social problems result from our stingy support system for single mothers and their children. But the link between criminality and fatherlessness holds even in countries with lavish social welfare systems.

Ah, the link between criminality and fatherlessness again. So ingrained is the assumption that crime rates always go up that conservatives making this argument do not even see the need to account for the incredible, world-historical drop in violence that has accompanied the collapse of the nuclear family. I know Kay Hymowitz knows this, because we’ve argued about it before. But if her editors and readers don’t, why should she make a big deal out of it?

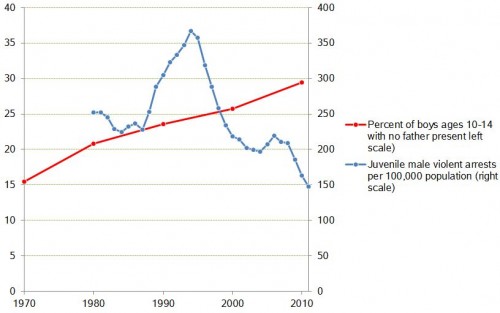

In this graph I show the scales down to zero so you can see the proportional change in each trend: father-not-present boys ages 10-14 and male juvenile violent-crime arrest rates.

I’m not arguing about whether boys living without fathers are more likely to commit crimes. I’m just saying that this is very unlikely to be the major cause of male juvenile violent crime if the trends can move so drastically in opposite directions at the same time. These aren’t little fluctuations. Even if you leave out the late-80s-early-90s spike in crime, arrests fell about 40% from 1980 to 2010 while father-absent boys increased almost 50%.

If you are going to argue for a strong association — which Hymowitz does — and use words like “tide,” you should at least acknowledge that the problem you are trumpeting is getting better while the cause you are bemoaning is getting worse.

Cross-posted at Family Inequality.

Philip N. Cohen is a professor of sociology at the University of Maryland, College Park, and writes the blog Family Inequality. You can follow him on Twitter or Facebook.