For the last week of December, we’re re-posting some of our favorite posts from 2011. Originally cross-posted at Ms.

————————

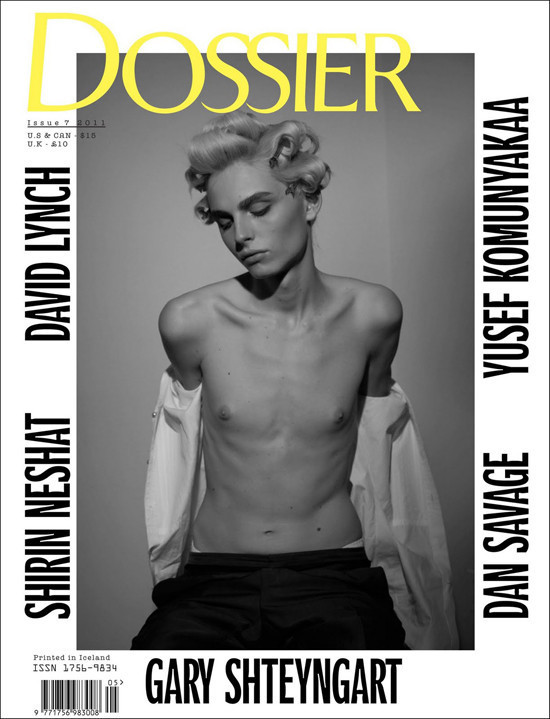

The cover of this month’s Dossier Journal magazine has caused a great stir. In a matter of a few hours, five readers — Andrew, Jessica B., anthropology professor Kristina Kilgrove, artist Thomas Gokey, and my brilliant colleague, music professor David Kasunic — all sent in a link. Here’s what all the fuss is about:

(source)

(source)

The model is a man named Andrej Pejic, with hair and make-up usually seen only on women, sliding his shirt off his back. Some might say that he is gender-ambiguous and the image deliberately blurs gender; are we seeing a chest or small breasts? It is not immediately apparent.

Both Barnes & Noble and Borders “bagged” the magazine, like they do pornographic ones, such that one can see the title of the magazine but the rest of the cover is hidden. Barnes and Noble said that the magazine came that way, representatives for Dossier say that the bookstore “chains” required them to do it (source). Non-ambiguously-male chests pepper most magazine racks, but this man’s chest hints at boobs. And so he goes under.

What’s going on?

Explaining why it is legal for men to be shirtless in public but illegal for women to do the same, most Americans would probably refer to the fact that women have breasts and men have chests. Breasts, after all, are… these things. They incite us, disgust us, send us into grabby fits. They’re just so there. They force us to contend with them; they’re bouncy or flat or pointy or pendulous and sometimes they’re plain missing! They demand their individuality! Why won’t they obey some sort of law and order!

Much better to contain those babies.

Chests… well they do have those haunting nipples… but they’re just less unruly, right? Not a threat to public order at all.

So, there you have it. Men have chests and women have breasts and that’s why topless women are indecent.

Of course it’s not that straightforward.

It’s not true that women have breasts and men have chests. Many men have chests that look a bit or even a lot like breasts (there is a thriving cosmetic surgery industry around this fact). Meanwhile, many women are essentially “flat chested,” while the bustiness of others is an illusion created by silicone or salt water. Is it really breasts that must be covered? Clearly not. All women’s bodies are targeted by the law, and men’s bodies are given a pass, breasty or chesty as they may be.

Unless.

Unless that man’s gender is ambiguous; unless he does just enough femininity to make his body suspect. Indeed, the treatment of the Dossier coverreveals that the social and legislative ban on public breasts rests on a jiggly foundation. It’s not simply that breasts are considered pornographic. It’s that we’re afraid of women and femininity and female bodies and, if a man looks feminine enough, he becomes, by default, obscene.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.