Flavia Dzodan, of Red Light Politics, sent in a link to the Global Media Monitoring Project’s new report, Who Makes the News? The document looks at the gender imbalance in news production, based on an analysis of 1,281 newspapers, TV, and radio stations in 108 countries on November 10, 2009.The results indicate that women are still under-represented as news subjects, and that stories about women often reinforce stereotypes (focusing on women in family roles, using women for “ordinary person” quotes rather than experts, emphasizing women in stories about criminal victimization, birth control, and so on but not economic policy or politics, etc.).

A note on the methodology:

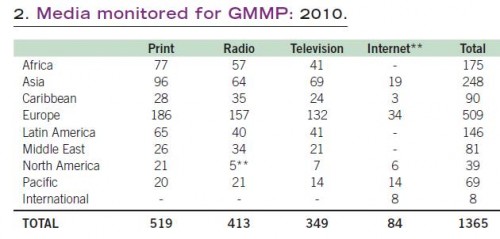

The research covered 16,734 news items, 20769 news personnel (announcers, presenters and reporters), and 35,543 total news subjects, that is people interviewed in the news and those who the news is about.

Internet sources were analyzed separately.

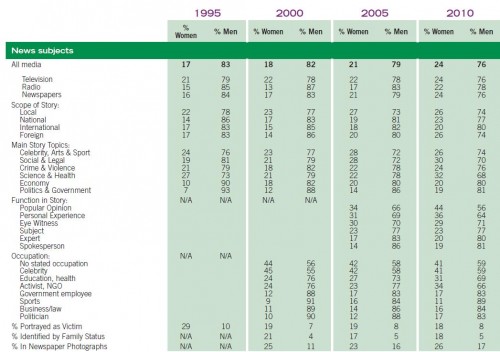

Overall, the analysis shows that both local and international news show a world in which men are highly over-represented as subjects, though women are more likely to be represented as victims, to have their family status mentioned, or to be in newspaper photos:

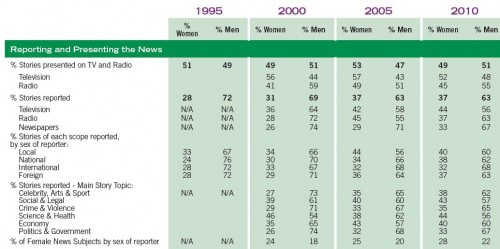

Interestingly, those reporting the news are more gender balanced, indicating that having more women producing the news doesn’t lead to an automatic reduction in under-representation of women in the news:

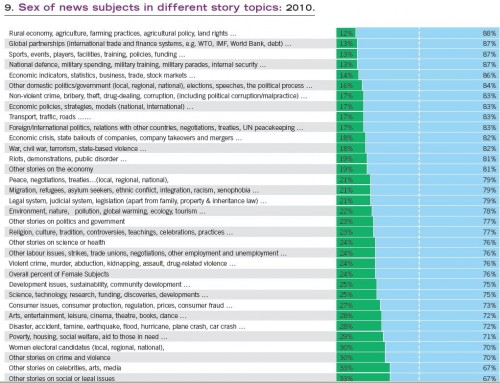

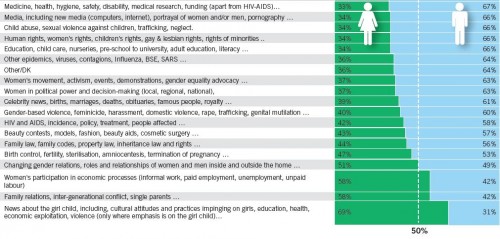

The representation of women as news subjects differs widely by category of news, from 12% of subjects in stories about agriculture to 58% in stories about family relations or single parenting (and 69% in a category they called the “girl-child,” stories about cultural practices impinging on or harming specifically female children, as opposed to children in general):

I’ll put the rest after the jump since there are quite a few images.