When companies advertise their products in largely segregated markets, they can tell different, even opposing stories to different groups of people with confidence that the messages will reach their intended audience, and not the unintended one. In an earlier post, for example, we showed how Basil Hayden Bourbon, Miller Lite, and Crown Royal were advertised differently in separated markets.

I was reminded of this phenomenon when DPK, as well as Sean M. of Santa Fe College, submitted this ad for Coca Cola in China. The ad ran during the 2008 Olympics. In fact, the Coca Cola company has partnered with the Olympics for over 80 years, so the fact that they advertised there isn’t surprising; they spent $75 million dollars advertising in China that year.

The slogan, “Red Around the World,” clearly references the color of Coca Cola marketing, but it is also the color China uses to represent itself, as well as the color associated with communism. Meanwhile, the visual of the ad invokes communist propaganda. Coca Cola appears to be solidly on China’s side in this ad, even leading the charge towards a Chinese communist take-over of the world (if I may be a bit dramatic).

This is in stark contrast to the long-standing effort by Coca Cola to market itself as a distinctly American drink.

.jpg)

I am supposing here that the ability to target their marketing to the Chinese (even during the Olympics?) offered Coca Cola some protection from a backlash against the company from both the left and the right (based on the argument that Coca Cola is pro-China/pro-communism/anti-human rights).

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

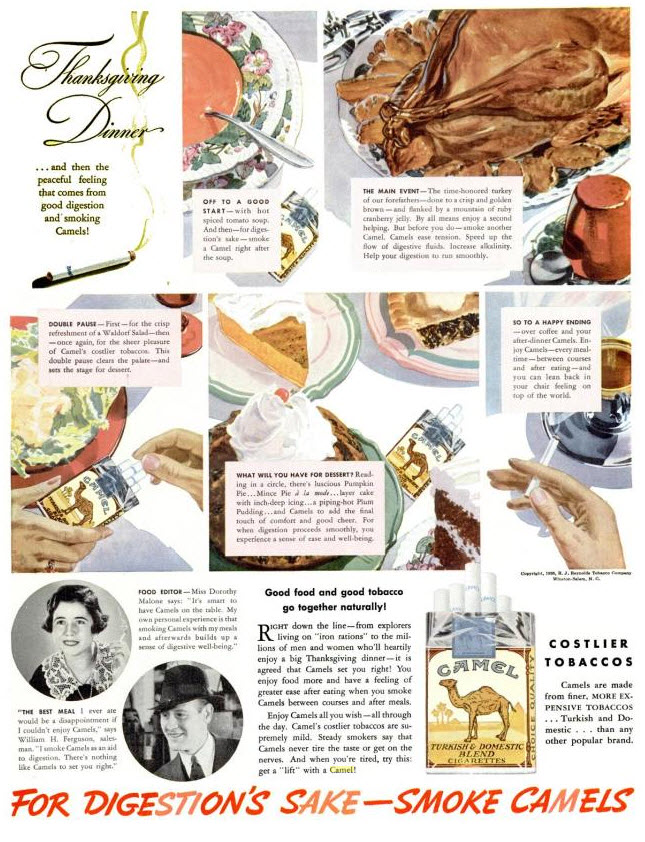

I am hard pressed to imagine that such an ad would fly today. That these ads would not only be un-palatable, but impermissible, is evidence that the power of corporations is not absolute.

I am hard pressed to imagine that such an ad would fly today. That these ads would not only be un-palatable, but impermissible, is evidence that the power of corporations is not absolute.