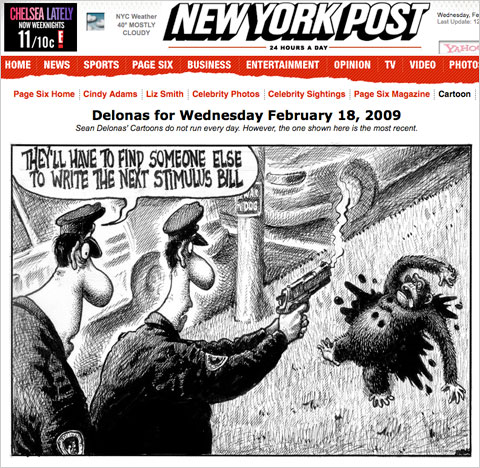

This cartoon is currently causing quite a stir in both the political realm and the blogosphere (thanks to Sewell C. and Franklin S. for pointing it out):

The question is, is this a racist cartoon? According to the NYT,

The chimpanzee was an apparent reference to the 200-pound pet chimpanzee that was shot dead by a police officer in Stamford, Conn., on Monday evening, after it mauled a friend of his owner.

You can read another account of it at Gawker.

So what is the implication? That the bill is so messed up a chimp must have written it? That he mauled the budget the way he mauled his owner’s friend? Given that the stimulus bill is widely associated with Obama (despite the fact that he, of course, did not write it–a bunch of Congressional staffers and policy geeks did, I suspect), it seems likely that many people will make a jump from the supposed author of the stimulus bill to Obama, meaning the chimp is a stand-in for the President. Is that the cartoonist’s intent? If so, is that intent inherently racist?

Of course, there’s some historical context here. As this post illustrates, there is a long history of Africans and African Americans being portrayed as ape-like, or even as a link between apes and Europeans in the Great Chain of Being. Can we use monkeys as caricatures of African American public figures without bringing some of the old racist overtones along as well?

Again from the NYT:

In a statement, Col Allan, editor in chief of The Post, denied Mr. Sharpton’s assertion that the cartoon was “racially charged.” Mr. Allan said:

The cartoon is a clear parody of a current news event, to wit the shooting of a violent chimpanzee in Connecticut. It broadly mocks Washington’s efforts to revive the economy. Again, Al Sharpton reveals himself as nothing more than a publicity opportunist.

The cartoon brings up some interesting issues surrounding artistic intent and reader interpretation. The cartoonist may or may not have meant to be in any way drawing on the older association between African Americans and apes. It’s likely that a fair number of readers will interpret the image that way, though, regardless of what the intent might be. Some will laugh and others will be offended at the implication. This gets at the crux of many conflicts over media images, TV shows, etc.: which matters, the stated intent of the creator, or what consumers of the material interpret it to be or what they do with it? And of course, the stated intent of the creator might be a bit disingenuous too; you can certain claim to have no racist intent while using imagery that is very much associated with racism, racial violence, etc.

Anyway, it’s a conversation starter, I guess.

Also, for the record, chimps make bad pets! They’re really strong and have sharp teeth. The live a long time. They reach sexual maturity and get frustrated and aggressive. Just go adopt a dog!