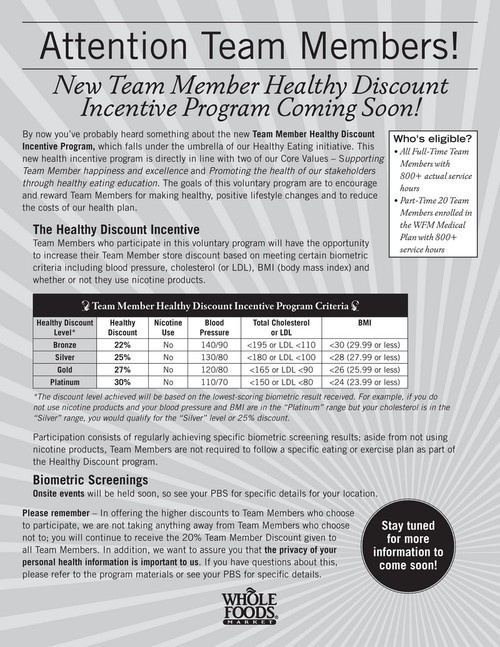

Nicolé L.-G. sent along a story on Jezebel about a new policy that Whole Foods is offering to its employees. Whole Foods has heretofore offered a 20% discount to all employees but, from now on, employees who are willing to undergo surveillance of a selection of body measures (blood pressure, cholesterol tests, and BMI calculations) and refrain from nicotine use, can try to qualify for better discounts:

Whole Foods specifies that you are only allowed the discount that correlates with your “worst” measure. So, even if you’re a non-smoker with 110/70 blood pressure and <150 or LDL <80 cholesterol, if you have a BMI of 30 or higher, you’re stuck at the “Bronze” level.

As has been discussed on this blog, and excellently at Shapely Prose, BMI does not translate directly into “health.” But Nicolé did a great job offering some additional analysis of this policy. She wrote:

…according to the popular media’s perception of weight management, eating healthy (whole) foods is one of the best ways to achieve health, so why make it easier (cheaper) for already “healthy” people to continue eating healthy and make it harder (more expensive) for “unhealthy” people to eat better quality food? I wonder how the employees with a healthy (thin) appearance would have felt if the increased discount was given to those with bad cholesterol, higher BMI’s and high blood pressure?!

Then there’s the idea that your employer will now be keeping track of your health information! It supports the idea that our bodies and weight (across genders) are being relegated to the role of either a commodity or liability for a company; useful for aiding or damaging the bottom-line. The way [CEO John] Mackay speaks of the collection of the “bio-marker” data as being cheap or expensive denotes a sense of ownership that the company then has over our physical autonomy that no company has a right to.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.