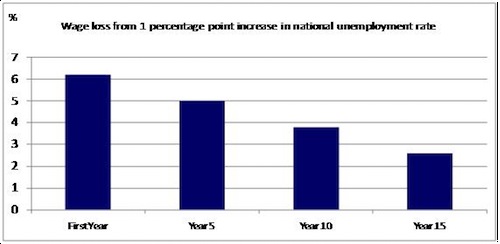

Existing data suggests that, for college students graduating during an economic recession, wage depression will follow them throughout their life. The figure below shows that, for every one percentage point increase in the national unemployment rate, a college grad’s wages will drop by about six percent. Five years later, their wages will still lag by five percent. Fifteen years later they’ve recovered their losses to about three percent, but they’re still behind where they would have been. And remember, this data is for each percentage point increase in the unemployment rate.

Data borrowed from the Office of Management and Budget, via Matthew Yglesias.

For more happy graduation news, see here.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.