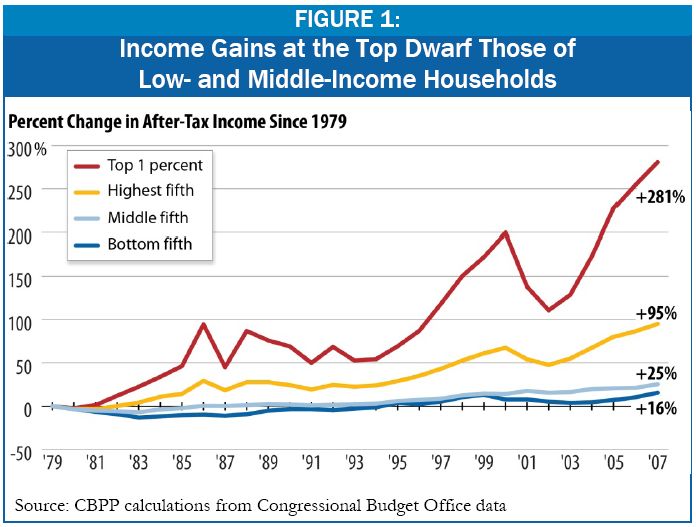

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities ran the CBO data on income and published a report showing the huge increase in inequality since 1979, especially in recent years (the data go up to 2007 – full report here). It’s the people at the top – the default swappers and hedge funders – who’ve been making out like bandits, while the rest of us limped slowly along.

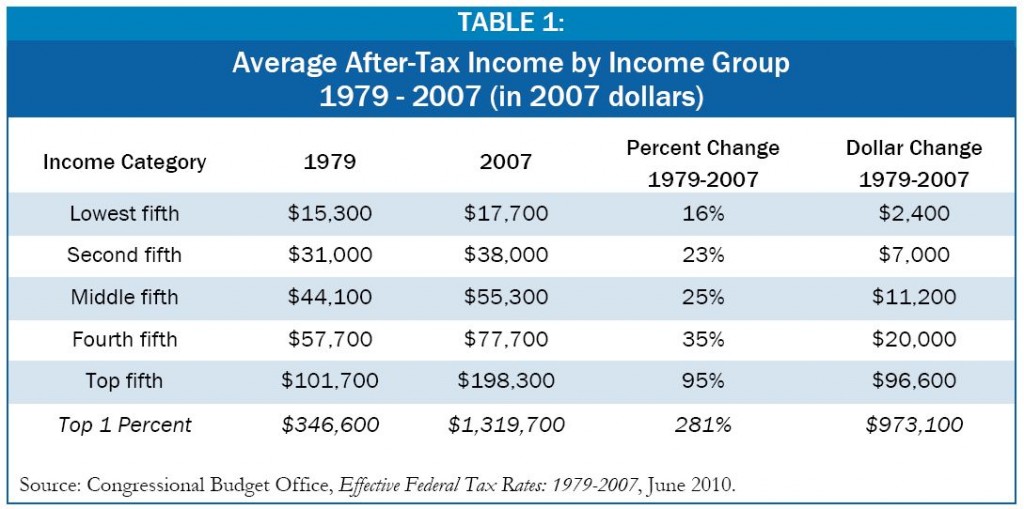

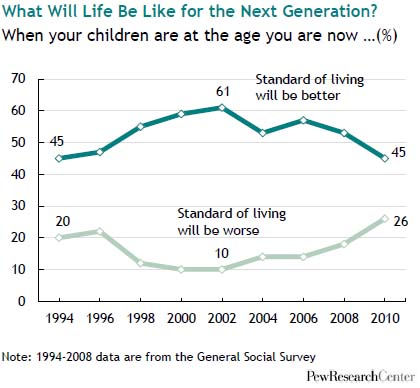

The graph shows percent changes. How much is that in American money?

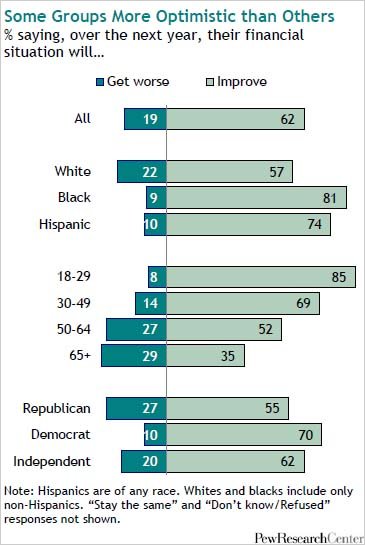

We all knew this. But I’m still surprised that supposedly intelligent people can still attribute it all to individual factors. Yes, individual differences in ability account for individual differences. But they don’t make for huge changes in the overall distribution.

But here we have Glenn Reynolds, Instapundit, one of the most widely read bloggers in the known universe (especially the conservative universe), reprinting the comment of a reader at a tax blog that posted the data.

A reason for the “wealth or income gap”: Smart people keep on doing things that are smart and make them money while stupid people keep on doing things that are stupid and keep them from achieving.

People who get an education, stay off of drugs, apply themselves, and save and wisely invest their earnings do a lot better than people who drop out of school, become substance abusers, and buy fancy cars and houses that they can’t afford, only to lose them.

We don’t have an income gap. We have a stupid gap.

Glenn calls it “the comment of the day.”

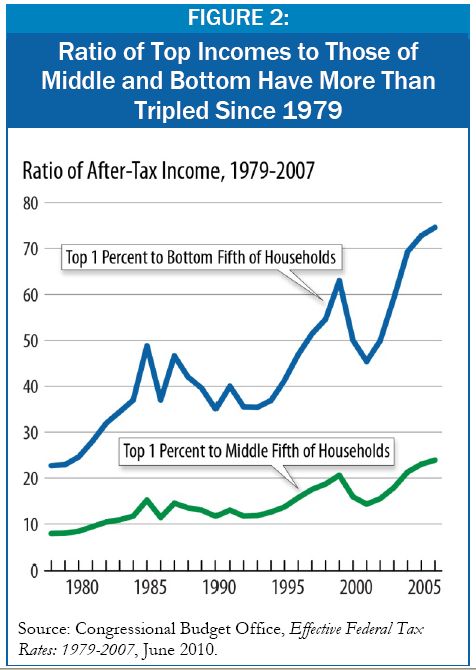

In 1993, the average household in the top 1% was making 36 times the income of a household in the lowest fifth. In the next 14 years, those top guys worked really hard while the poor apparently sold their diplomas to buy crack and Escalades, so by 2007 the gap had doubled. The richest now made 72 times the income of the poor.

The funny thing is that for a few years (1984- 1983 1993) the rich-poor gap was decreasing. It must have been all the cocaine those bond traders were doing.

The commenter is right – there may be a stupid gap. But it’s the gap that Durkheim suggested long ago. Some people look at “social facts” – large differences between one time or place and another – and try to explain them in terms of individual facts. Other people seek an explanation in social facts – facts about the society, facts which individuals have little power to change.

(HT: Mark Kleiman)