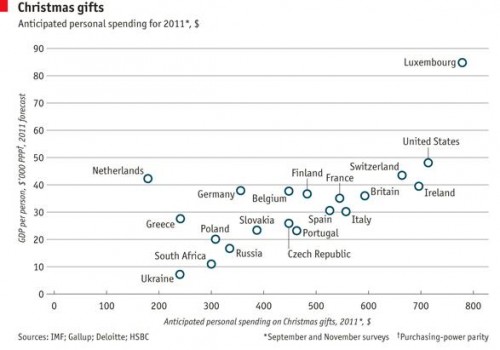

As we enter the last frenzied days of Christmas shopping, Dmitriy T.M. thought it was worth looking at international comparisons in spending on the holiday. The Economist posted a graph based on Gallup polls and other data sources about how much individuals in various countries in Europe, plus the U.S. and South Africa, plan to spend on Christmas shopping this year, plotted against national GDP. Overall, Christmas spending correlates with national wealth, with the Netherlands being a noticeable outlier (spending less than we’d expect) and Luxembourg in a spending league of its own: