The media likes to talk about markets as if they were just a force of nature. In fact, markets and their outcomes are largely shaped by political power. In a capitalist system like ours, that power is largely used to advance the interests of those who own and run our dominant corporations.

Thanks to Bloomberg News we have yet another example of this reality. In brief, as a result of Congressional and media pressure the Federal Reserve was recently forced to reveal its lending activity for the period August 2007 through April 2010. Bloomberg News examined these Federal Reserve records and found that the Fed secretly provided selected banks, brokerage houses, and even non-financial firms (such as General Electric and Ford) with at least $1.2 trillion in loans, often with minimal collateral required and at below market interest rates.

This money was given through more than a dozen lending programs. Many firms tapped multiple programs through multiple subsidiaries. Bloomberg arrived at its total by focusing on the seven largest programs, which included the Fed’s discount window and six temporary lending facilities (the Asset-Backed Commercial Paper Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility; the Commercial Paper Funding Facility; the Primary Dealer Credit Facility; the Term Auction Facility; the Term Securities Lending Facility; and so-called single- tranche open market operations).

If you like visuals, here is a 5 minute video that provides a good summary of what Bloomberg gleaned from its examination.

UPDATE: Embedding was disabled, but you can watch it here.

Bloomberg also has an interactive site that allows you to chart who got what and over what period.

Some of the highlights are as follows:

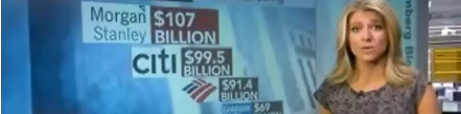

The largest borrower, Morgan Stanley, got as much as $107.3 billion, while Citigroup took $99.5 billion and Bank of America $91.4 billion . . .

Almost half of the Fed’s top 30 borrowers, measured by peak balances, were European firms. They included Edinburgh-based Royal Bank of Scotland, which took $84.5 billion, the most of any non-U.S. lender, and Zurich-based UBS AG, which got $77.2 billion. . . .

The $1.2 trillion peak on Dec. 5, 2008 — the combined outstanding balance under the seven programs tallied by Bloomberg — was almost three times the size of the U.S. federal budget deficit that year and more than the total earnings of all federally insured banks in the U.S. for the decade through 2010, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

The Federal Reserve fiercely resisted making its records public, arguing that doing so would stigmatize those institutions that received loans. A group of the largest commercial banks actually petitioned the Supreme Court in an unsuccessful effort to keep the loan information secret.

Perhaps one reason that the Federal Reserve and the banks were reluctant to have these records made public is that they raise significant questions of conflict of interest. According to a statement by Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders:

…the Fed provided conflict of interest waivers to employees and private contractors so they could keep investments in the same financial institutions and corporations that were given emergency loans.

For example, the CEO of JP Morgan Chase served on the New York Fed’s board of directors at the same time that his bank received more than $390 billion in financial assistance from the Fed. Moreover, JP Morgan Chase served as one of the clearing banks for the Fed’s emergency lending programs.

In another disturbing finding, the GAO said that on Sept. 19, 2008, William Dudley, who is now the New York Fed president, was granted a waiver to let him keep investments in AIG and General Electric at the same time AIG and GE were given bailout funds. One reason the Fed did not make Dudley sell his holdings, according to the audit, was that it might have created the appearance of a conflict of interest.

Another reason may be that the Federal Reserve didn’t want it known that it was deviating from its past practice of requiring borrowers to provide secure collateral, which was normally either Treasuries or corporate bonds with the highest credit rating, and never stocks. For example:

Morgan Stanley borrowed $61.3 billion from one Fed program in September 2008, pledging a total of $66.5 billion of collateral, according to Fed documents. Securities pledged included $21.5 billion of stocks, $6.68 billion of bonds with a junk credit rating and $19.5 billion of assets with an “unknown rating,” according to the documents. About 25 percent of the collateral was foreign-denominated.

Moreover, as Bloomberg News also reported, many Fed loans were made at below market interest.

On Oct. 20, 2008, for example, the central bank agreed to make $113.3 billion of 28-day loans through its Term Auction Facility at a rate of 1.1 percent, according to a press release at the time.

The rate was less than a third of the 3.8 percent that banks were charging each other to make one-month loans on that day. Bank of America and Wachovia Corp. each got $15 billion of the 1.1 percent TAF loans, followed by Royal Bank of Scotland’s RBS Citizens NA unit with $10 billion, Fed data show.

These loans were absolutely critical to the survival of our leading companies. A case in point:

Citigroup was in debt to the Fed on seven out of every 10 days from August 2007 through April 2010, the most frequent U.S. borrower among the 100 biggest publicly traded firms by pre- crisis market valuation. On average, the bank had a daily balance at the Fed of almost $20 billion.

These loans are also a key reason that our post-Great Recession economy remains largely unchanged in structure. In other words, it was the exercise of political power, rather than so-called market dynamics or efficiencies, that explains the financial industry’s continuing profitability and economic dominance.

Now imagine if we had a state that engaged in transparent planning and was committed to using our significant public resources to reshape our economy in the public interest. As we have seen, state planning and intervention in economic activity already goes on. Unfortunately, it happens behind closed doors and for the benefit of a small minority. It doesn’t have to be that way.