Cross-posted at Reports from the Economic Front.

Media and policy-makers seem anxious to convince us that the economy is in strong recovery mode, therefore, no further significant policy interventions are needed.

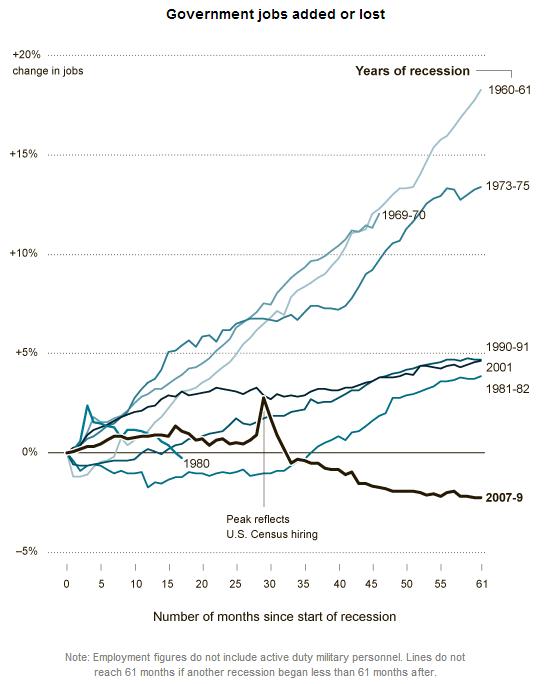

Their optimism appears to rest heavily on the recent acceleration in consumer spending. After all, there are strong reasons for concern with the other major sources of growth: government spending on all levels is being cut, exports face a weakening world economy, and business investment remains largely stagnate.

But there are also strong reasons to challenge this optimistic view of consumer spending as a growth engine. The charts below, from a Wall Street Journal article, highlight some of the most important.

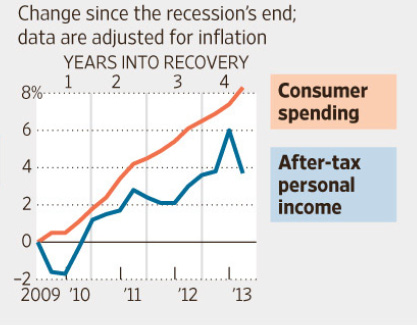

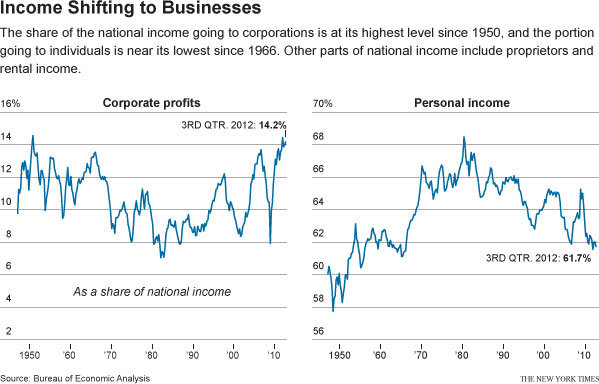

As we see below, while consumption spending is indeed accelerating, after tax personal income is falling. In other words, there appears little reason to believe that there is a solid foundation for sustaining this trend.

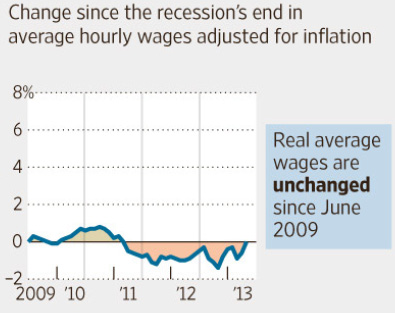

Additionally, after four years of recovery we still have 2.4 million fewer jobs than we had at the start of the recession. Moreover, as we see below, there has been no real wage growth. In fact, real average wages have fallen for most of the so-called expansionary period.

Yes, housing values are finally starting to rise and household debt payments as a share of after-tax income are declining. But to a large extent the new burst in consumption spending has more to do with renewed borrowing than solid gains in job creation and income.

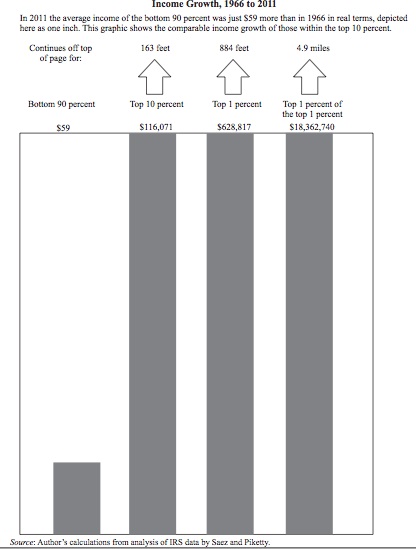

Unfortunately, there is little reason for us to have confidence that the economy is gathering strength in ways that will be sustainable or benefit the great majority of working people.

Martin Hart-Landsberg is a professor of economics at Lewis and Clark College. You can follow him at Reports from the Economic Front.