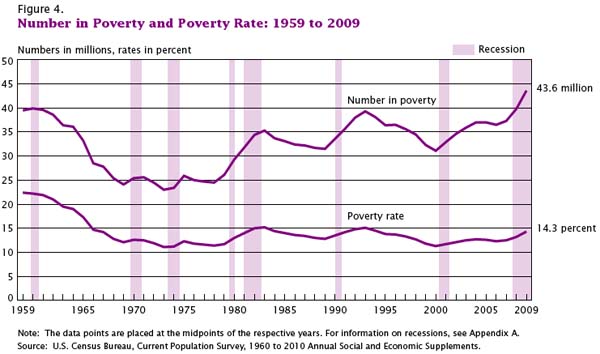

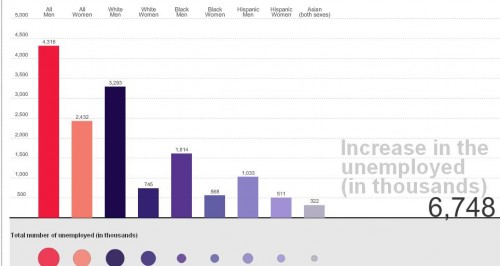

This week the U.S. Census Bureau reported that the American poverty rate has reached 14.3%, the highest it has been in 15 years:

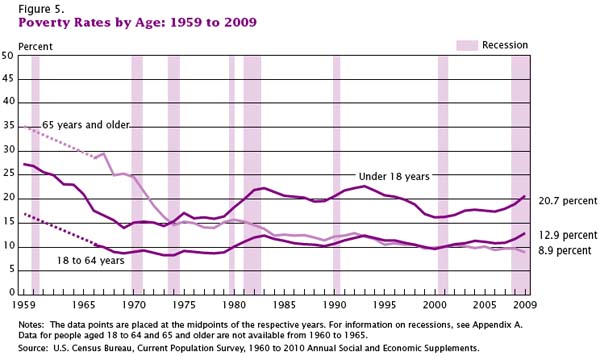

Children are over-represented among the poor; among those less than 18-years-old, the poverty rate is 20.7%:

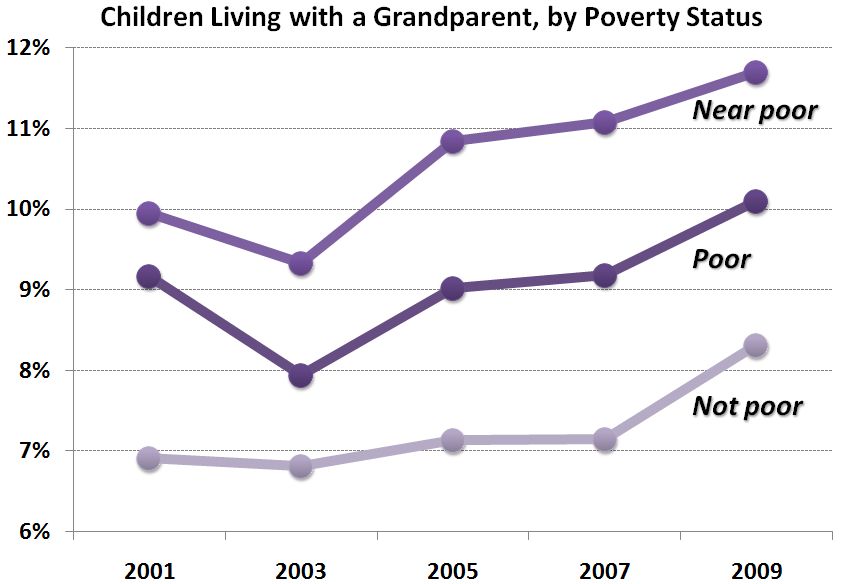

The Census report suggests that the poverty rate would be even higher if it weren’t for an increase in non-nuclear family households. Over the last two years, an additional 11.6 percent of households now include non-family or family members from three generations or more. Consider this data from Philip Cohen’s Family Inequality blog (and notice that the near poor are more likely to be living with a grandparent than the poor, who may not have this option):

So, the economic recession is correlated with an increase in poverty, but what does “poverty” really mean? The New York Times reports that in 2009 it meant a pretax income of $10,830 for a single person with no dependents and less than twice that, $22,050, for a family of four.

Trying to imagine keeping a roof over my head, sufficient food in my belly, and clothes on my back on that amount of money is difficult. But even if this was possible, human beings need more than food, shelter, and clothes. Try to imagine, with this amount of money, maintaining friendships and romantic partnerships, nurturing your children’s emotional health and educational potential, having pride and comfort in your home and personal appearance, finding the resources to invest in your own human capital, or giving yourself a modicum of leisure. Poor people are human too and these numbers only begin to scratch the surface of the kind of deprivation many Americans suffer every day.

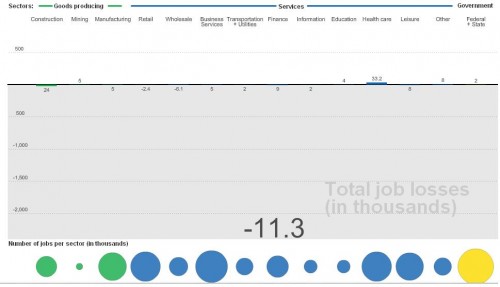

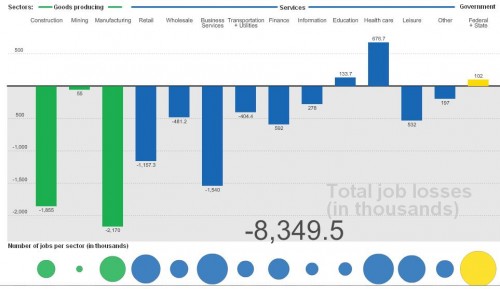

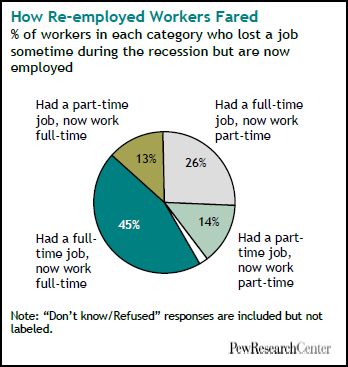

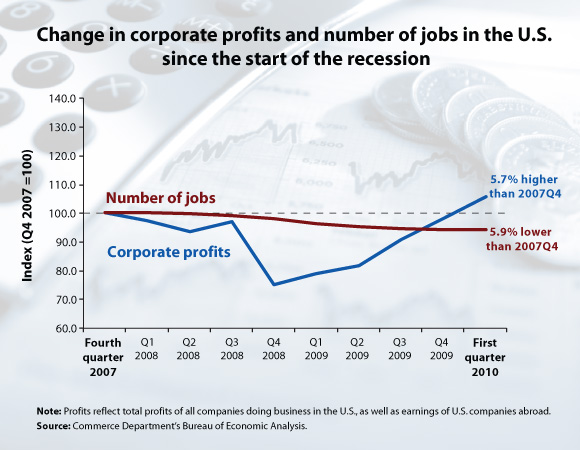

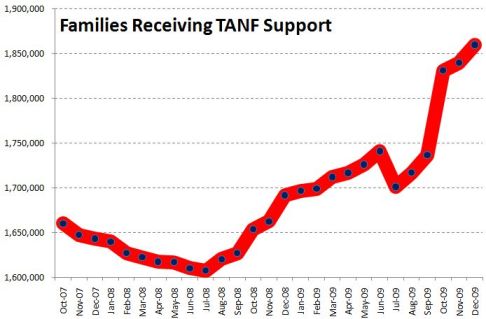

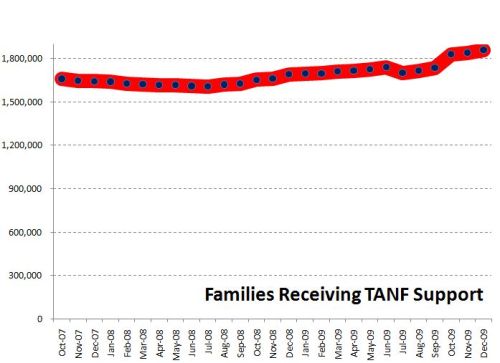

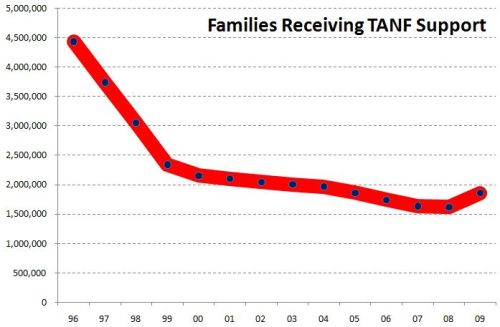

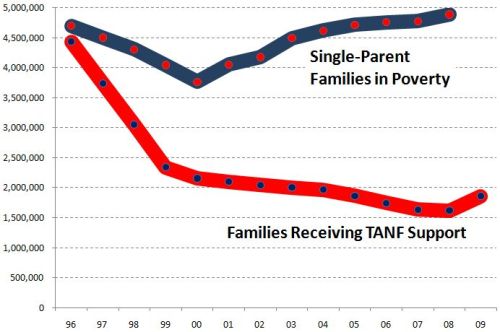

Images borrowed from Graphic Sociology.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.