Cross-posted at Ms.

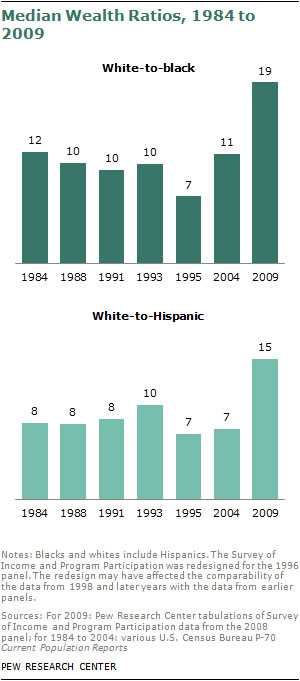

A new study from the Pew Research Center reports staggering racial gaps in median wealth — a person’s accumulated assets minus her debt — between whites ($113,149), blacks ($5,677) and Latinos ($6,325). That’s a 20-to-1 white-to-black ratio of wealth and a 18-to-1 white-to-Latino ratio.

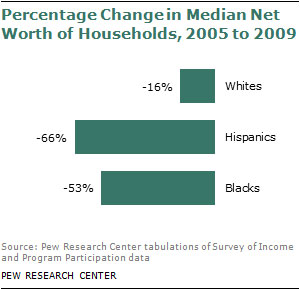

Essentially, all of the economic gains made by people of color since the Civil Rights Movement have been erased in a few years by the Long Recession. Whites experienced a net wealth loss of 16 percent from 2005 to 2009, while blacks lost about half of their wealth (53 percent) and Latinos lost two-thirds of their wealth.

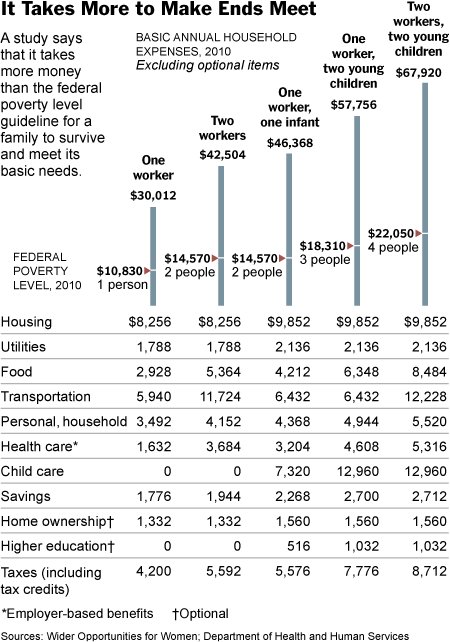

Media outlets reporting on the Pew study point to housing loss as the primary culprit, since the net worth of blacks and Latinos is heavily reliant on home ownership, while whites are more likely to have retirement accounts and stock.

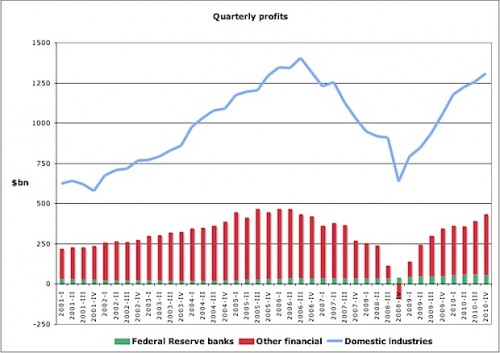

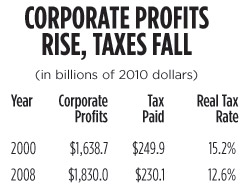

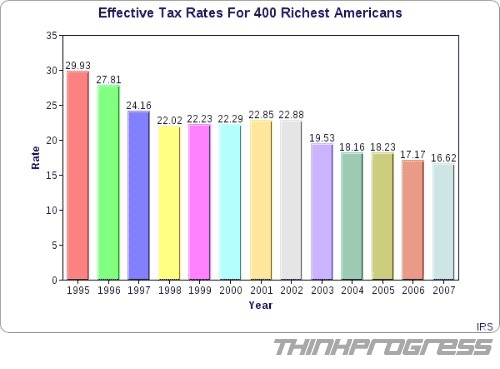

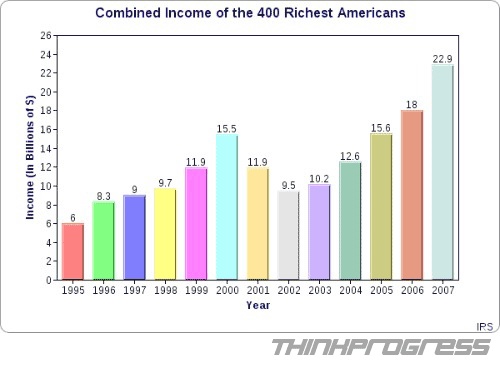

While this is certainly accurate, it obscures the core racism at play. Public policy decisions have been responsible for the speedy recovery of the financial market and the slow recovery of the housing market. From the start, the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) favored Wall Street recovery over homeowner recovery, with only $12 billion of the $700 billion bailout spent on foreclosure programs. (To be fair, most of the Wall Street money was eventually paid back.)

So prioritization of corporate interests disproportionately assisted whites in the recovery — but (perhaps) not intentionally. The same cannot be said for actual lending practices.

Rampant– — and racist — fraud in the home loan industry was a primary contributor to the collapse, with 61 percent of sub-prime loan holders actually qualifying for prime loans that would have been easier to maintain. Blacks and Latinos were especially targeted for sub-prime loans, a practice called “reverse redlining.” Wells Fargo loan officer-turned-whistle blower Elizabeth Jacobson admitted that her company specifically went after African Americans for sub-prime loans through “wealth building” conferences hosted in black churches.

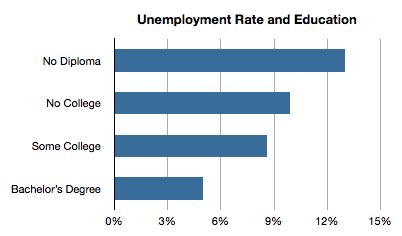

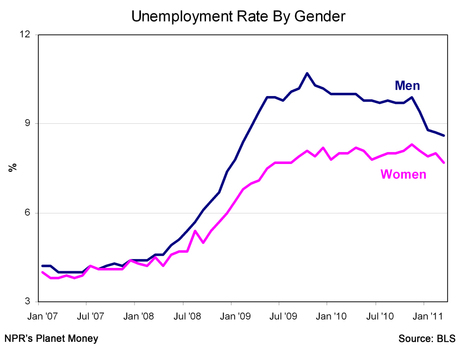

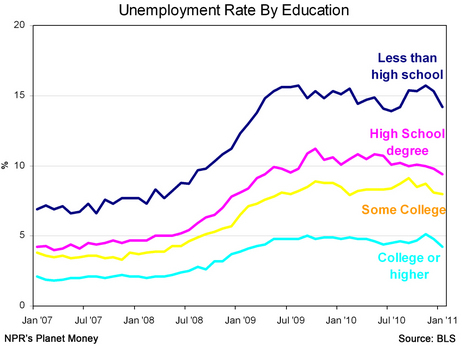

The employment gap between whites and blacks is also a contributor to the wealth gap. While white American are suffering through the Long Recession with 7.9 percent unemployment, blacks are experiencing Great Depression-like figures of 16.1 percent unemployment. This figure jumps to 31.4 percent for blacks ages 16 to 24, and black Americans have consistently had the higher rate of unemployment compared to white Americans since 2007.

Not surprisingly, the employment gap, too, has racist origins. The Center for American Progress analyzed unemployment data from the last three recessions and found that black unemployment starts earlier, rises faster and lingers longer. Explanations include the concentration of black workers in the stumbling manufacturing sector, the cutting of public sector jobs — and racial discrimination. This last finding is no shock given that employers are more likely to call back a white job applicant with a criminal record than a similarly qualified black man without a record.

The role of racism in poverty is important to keep in mind at a time Washington politicians are manufacturing crises that will slash the entitlement programs that 1 in 6 Americans rely on. It’s ironic that we’re cutting safety nets for the poor just as we’re experiencing the highest poverty rate since 1960, with blacks and Latinos three times as likely to live in poverty. Public policy is supposed to knock down racial and other non-meritorious barriers to pursuing life, liberty, and happiness, not jack them higher.