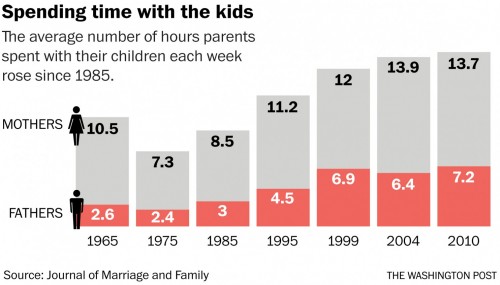

While the ’50s is famous for its family-friendly attitude, the number of hours that parents spend engaged in childcare as a primary activity has been rising ever since:

The driving force behind all this focused time is the idea that it’s good for kids. That’s why parents often feel guilty if they can’t find the time or even go so far as to quit their full-time jobs to make more time.

This assumption, however, isn’t bearing out in the science, at least not for mothers’ time. Sociologist Melissa Milkie and two colleagues just published the first longitudinal study of mothers’ time investment and child well-being. They found that the amount of time mothers spent with their children had no significant impact on their children’s academic achievement, incidence of behavioral problems, or emotional health.

Quoted at the Washington Post, Milkie puts it plainly:

I could literally show you 20 charts, and 19 of them would show no relationship between the amount of parents’ time and children’s outcomes… Nada. Zippo.

Benefits for adolescents, they argued, were more nuanced, but still minimal.

These findings suggest that the middle-class intensive mothering trend may be missing its mark. As Brigid Shulte comments at the Washington Post, it’s really the quality, not the quantity that counts. In fact, Milkie and colleagues did find that “family time” — time with both parents while engaged in family activities — was related to some positive outcomes.

The findings also offer evidence that women can work full-time, even the long hours demanded in countries like the U.S., and still be good mothers. Shulte points out that the American Academy of Pediatrics actually encourages parent-free, unstructured time. Moms just don’t need to always be there after all, freeing them up to be people, workers, partners, and whatever else they want to be, too.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.