What should we make of changes in fashion? Are they the visible outward expression of new ways of thinking? Or do fashions themselves influence our sentiments and ideas? Or are fashions merely superficial and without any deeper meaning except that of being fashionable?

It’s summer, and once again magazines and newspapers are reporting on beachwear trends in France, proclaiming “the end of topless.” They said the same thing five years ago.

As in 2009, no systematic observers were actually counting the covered and uncovered chests on the beach. Instead, we are again relying on surveys – what people say they do, or have done, or would do. Elle cites an Ipsos survey: “In 2013, 93% of French women say that they wear a top, and 35% find it ‘unthinkable’ to uncover their chest in public.”

Let’s assume that people’s impressions and the media stories are accurate and that fewer French women are going topless. Some of stories mention health concerns, but most are hunting for grander meanings. The Elle cover suggests that the change encompasses issues like liberty, intimacy, and modesty. Marie-Claire says,

Et en dehors de cette question sanitaire, comment expliquer le recul du monokini : nouvelle pudeur ou perte des convictions féministes du départ ?

But aside from the question of health, how to explain the retreat from the monokini: a new modesty or a loss of the original feminist convictions? [my translation, perhaps inaccurate]

The assumption here is that is that ideas influence swimwear choices. Women these days have different attitudes, feelings, and ideologies, so they choose apparel more compatible with those ideas. The notion certainly fits with the evidence on cultural differences, such as those between France and the U.S.

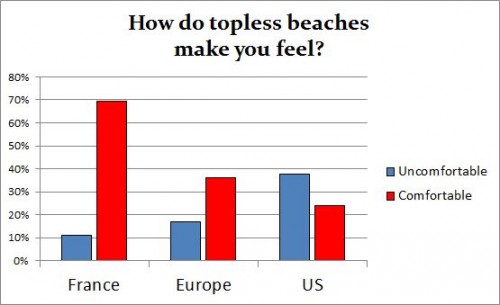

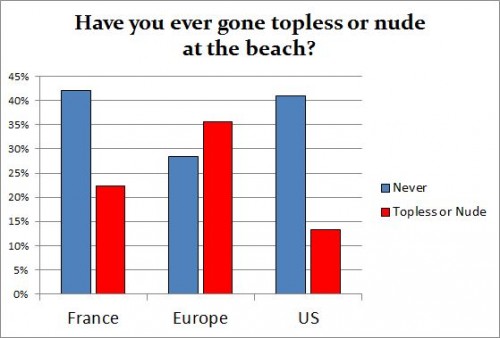

Americans are much more likely to feel uncomfortable at a topless beach. But they are also much less likely to have been to one. (Northern Europeans – those from the Scandinavian countries and Germany – are even more likely than the French to have gone topless.) (Data are from a 2013 Harris survey done for Expedia.)

This second graph could also support the other way of thinking about the relation between fashion and ideas: exposing your body changes how you think about bodies. If people take off their clothes, they’ll become more comfortable with nudity. That is, whatever a woman’s original motivation, once she did try going topless, she would develop ideas that made sense of the experiences, especially since the body already carries such a heavy symbolism. She would not have to invent these topless-is-OK ideas all by herself. They would be available in the conversations of others. So unless her experiences were negative, these new ideas would add to and reinforce the thoughts that led to the original behavior.

This process is much like the general scenario Howie Becker outlines for deviance.

Instead of deviant motives leading to deviant behavior, it is the other way around; the deviant behavior in time produces the deviant motivation. Vague impulses and desires … probably most frequently a curiosity … are transformed into definite patterns of action through social interpretation of a physical experience. [Outsiders, p. 42]

With swimwear, another motive besides “vague impulses” comes into play: fashion – the pressure to wear something that’s within the range of what others on the beach are wearing.

Becker was writing about deviance. But when the behavior is not illegal and not all that deviant, when you can see lots of people doing it in public, the supportive interpretations will be easy to come by. In any case, it seems that the learned motivation stays learned. The fin-du-topless stories, both in 2009 and 2014, suggest that the change is one of generations rather than a change in attitudes. Older women have largely kept their ideas about toplessness. And if it’s true that French women don’t get fat, maybe they’ve even kept their old monokinis. It’s the younger French women who are keeping their tops on. But I would be reluctant to leap from that one fashion trend to a picture of an entire generation as more sexually conservative.

Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.