Cross-posted at Montclair SocioBlog.

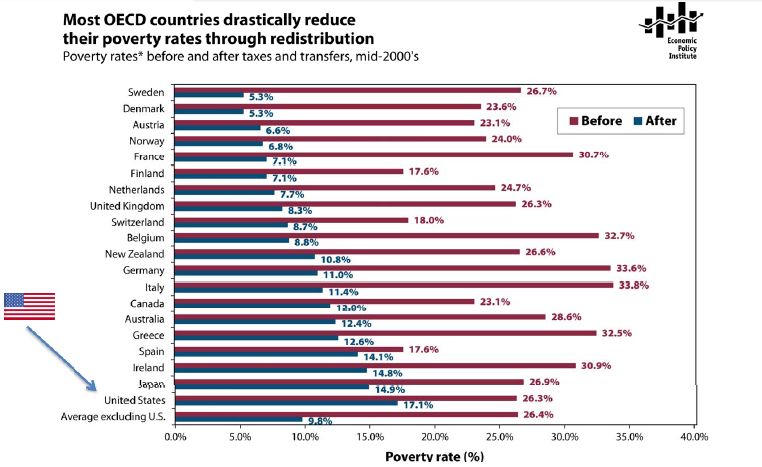

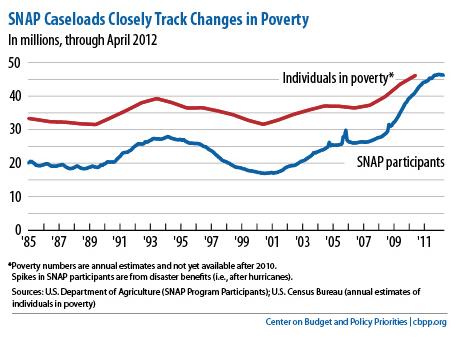

The poverty rate in the US in the mid-2000s was about 17%. In Sweden, the poverty rate was 5.3%; in Germany, 11%. That was the rate after adding in government transfers. In Germany, the poverty rate before those transfers was 33.6%, ten points higher than that in the US. Sweden’s pre-transfer poverty rate was about the same as ours.

Jared Bernstein has this chart showing pre-transfer and post-transfer rates for the OECD countries (click to enlarge):

Three points:

1. Governments have the power to reduce poverty, and reduce it a lot. European governments do far more towards this goal than does the US government.

2. It’s unlikely that America’s poor people are twice as lazy or unskilled or dissolute as their European counterparts. Individual factors may explain differences between individuals, but these explanations have little relevance for the problem of overall poverty. The focus on individual qualities also has little use as a basis for policy. European countries have fewer people living in poverty, but not because those countries exhort the poor to lead more virtuous lives and punish them for their improvident ways. European countries have lower poverty rates because the governments provide money and services to those who need them.

3. The amount of welfare governments provide does not appear to have a dampening effect on the overall economy.